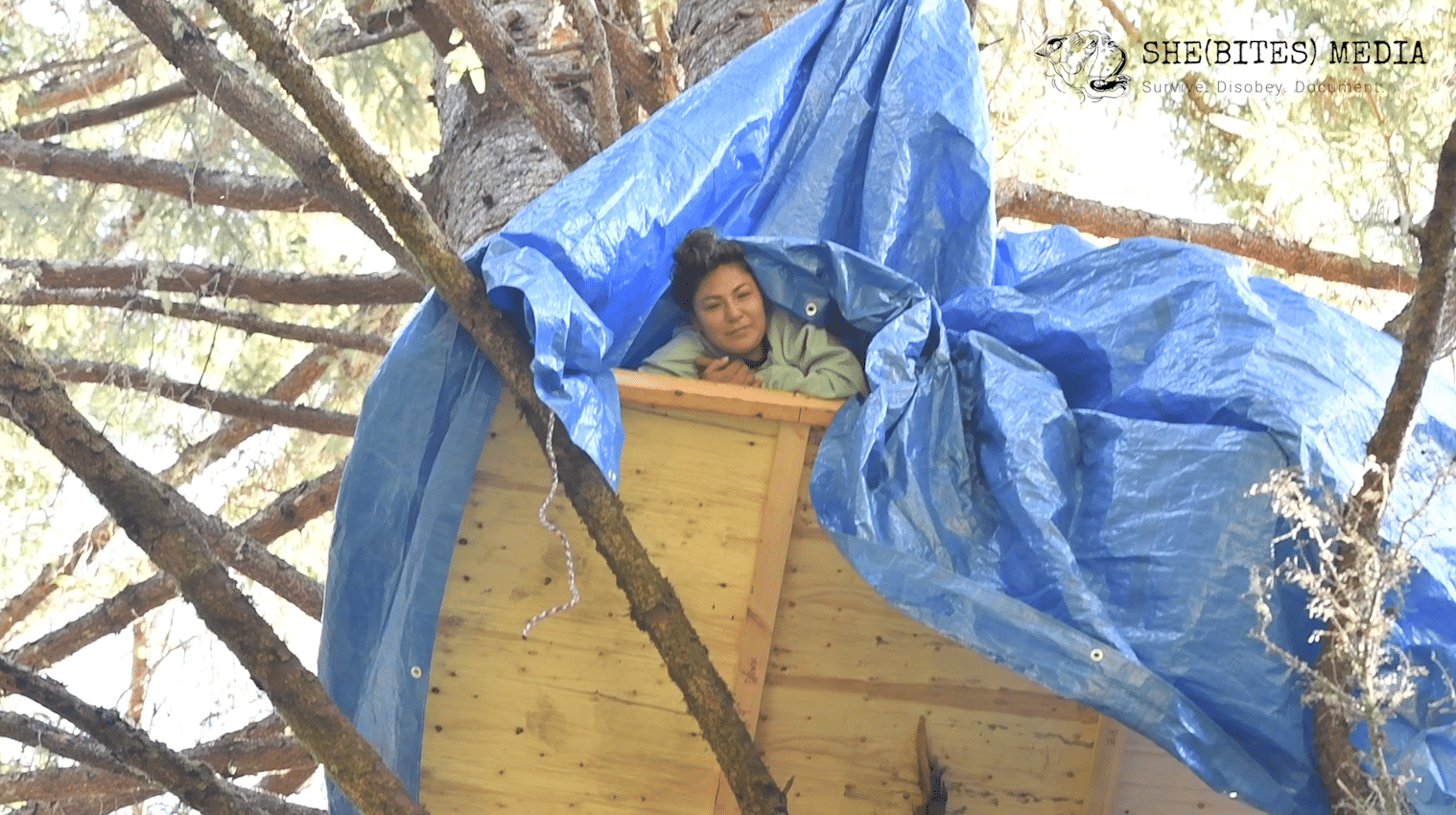

T’Sou-ke woman, who sat in a tree for nearly a month, says protest was about more than a single development

After avoiding police this week, wis-waa-cha (Kati George-Jim) says her action ‘was important to the bigger strategy of confronting the Indian Act’

A T’Sou-ke woman who took part in a tree-sit for nearly a month in protest of construction work at her First Nation says she avoided police who tried to confront her this week.

wis-waa-cha (Kati George-Jim) began sitting in a Sitka spruce on August 31 in opposition to an infrastructure upgrade at the First Nation — which she said threatens the coastal wetland habitat and impacts her family’s ability to practice their culture.

wis-waa-cha had been documenting the tree-sit on her social media, recording short videos about her time sitting in the spruce in her ancestral village site, Siaosun, located on southern “Vancouver Island.”

“On Sept 26, 2023, the RCMP ERT and CIRG militarized units came to violently remove me from the tree,” wis-waa-cha wrote in the captions of a video posted on Thursday.

“Thankfully, I evaded their arrest and brutality.”

wis-waa-cha had posted on her Instagram page that Tuesday that RCMP were present — something she had been anticipating after an injunction was served to her on Aug. 30.

“The violence that is used to enforce this injunction and criminalize us is here and, at this moment, trying to remove me for being in relationship to my land and practicing my own laws,” she said.

The RCMP confirmed officers had attended the construction worksite Tuesday morning to “keep the peace while industry conducted their work, knowing there was the possibility of a tree-sitter.”

Once on site however, RCMP spokesperson Alex Bérubé said there was nobody in the tree so industry “simply proceeded with their work.”

“There was no need for any police intervention,” Bérubé told IndigiNews via email.

In the video posted on her Instagram Thursday, wis-waa-cha clarified that she had avoided the officers, writing in the caption: “Update: They didn’t catch me.”

She said, ultimately, her protest “was important to the bigger strategy of confronting the Indian Act.”

“This is terror and violence against Indigenous land and beings every single day,” wis-waa-cha said in the video.

“The land is experiencing the violence and is sacrificed for colonial expansion. We share this heartbreak.”

“Our next action is unfolding now,” she added, but did not elaborate further. She was not immediately available for comment.

A clash of two legal systems

wis-waa-cha and her mother kWa’st’not (Charlene George) are against construction on the T’Sou-ke reserve, which involves the development of a gravity sanitary sewer collection system and wastewater pump station that would bring raw sewage from 53 homes on the reserve to the District of Sooke’s wastewater treatment plant.

T’Sou-ke Nation has received $11.4 million from Indigenous Services Canada to build this infrastructure, which would also support a new 22-lot subdivision of single and multi-family residential units.

wis-waa-cha said in a phone interview on Sept. 14 that she had only recently found out about the construction, which her family does not support because it is near their village site of Siaosun, used over generations, primarily for fishing in the summers.

It is also a coastal wetland zone, important for biodiversity, including black bears, cougars, hundreds of different birds and grass that is used for basket weaving.

“This was primarily used as a summer village site because of the temperature, because of the fish, because you have access to everything by the ocean,” she said.

“And it is still [used] as a village today — it’s never been surrendered.”

wis-waa-cha said she is against the construction because, along with being a sacred location, it is taking place on unceded and unsurrendered land. She said this makes it beyond the control of T’Sou-ke’s chief and council, which has been given power through the federal Indian Act.

Ultimately, there are two legal systems — Canadian common law and T’Sou-ke Indigenous law — clashing, wis-waa-cha wrote in a Facebook reel on Sept. 25.

kWa’st’not and wis-waa-cha first held a vigil on the road that leads to the construction worksite — on McMillan Road — on Aug. 18. Both women were served with an application for an injunction by the T’Sou-ke First Nation on Aug. 24, receiving a permanent injunction in a decision by the court on Aug. 30.

wis-waa-cha said the band also served an application via email notice for the RCMP to enforce an exclusion zone on Sept. 7.

The exclusion zone was granted by a British Columbia Supreme Court judge on Sept. 12, meaning the RCMP could forcibly remove her from the tree at any time moving forward.

“This means [the RCMP] can come in from a helicopter above me, or they can try climbing up below me,” she said in a reel posted to her Facebook on the same day. “Both ways are known not to be very safe, and both ways are illegally and forcibly removing me from my unceded land in T’Sou-ke territory.”

For wis-waa-cha, the band council’s response to the vigil and sit-in she and her mother undertook reflects a colonial response to environmental concerns.

“And the band is also acting in the same way that the municipality of Sooke or the province of British Columbia or Canada act — there is no regulation, there’s no regulatory body, and there’s nothing that would stop a band council from doing that over what they claim to be an Indian reserve.”

wis-waa-cha said sharing regular updates about the proposed development via her social media — on Facebook and Instagram — has been an important part of her protest because it’s not only about physical support but “larger systemic change.”

“It’s not one single problem, and it’s not about one development project,” wis-waa-cha said.

“It’s actually, for me personally, about the entire territory of British Columbia, which is currently being occupied in other ways — where they’re trying to create private property and undermine our Indigenous people’s ability for believing in the rightful responsibility of being in relation to the land and having homes on the land.”

‘Frustrating’

IndigiNews contacted the T’Sou-ke First Nation by phone and email with a request for comment about the proposed development but did not hear back. However, in an Aug. 19 article in the Victoria Times-Colonist, Chief Gordon Planes said the situation is “frustrating,” adding the council has asked the family to remove the blockade and leave the project site, saying that every day of the stoppage costs $24,000.

In a Sept. 7 article, Planes told the Times-Colonist there is a housing shortage in T’Sou-ke Nation and that studies and consultation on the project have been going on for years.

This includes four environmental studies and one archeological study for the project commissioned by the band since 2016.

wis-waa-cha said she wasn’t aware of any consultations taking place in the community. At the same time, she said she would not have attended the consultation meetings had she known about them because they are not the same as seeking consent.

“In our culture, in our laws, I would not need to go to a band council — it should be the other way around.”

The T’Sou-ke Nation maintains that no existing wetlands would be drained and filled.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

Book remembers ‘fighting spirit’ of Gino Odjick, hockey’s ‘Algonquin Assassin’

Biography of late Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg left winger explores Odjick’s legacy as enforcer in the rink — and Youth role model off the ice

-

St. Augustine’s survivor hopes for closure after evidence of 81 unmarked graves released

50 years after the residential ‘school’ closed, shíshálh Nation announces evidence of many burial sites. A Tla’amin Elder wonders how many more children died