Exhibition showcases remarkable life of George Clutesi, who safeguarded Nuu-chah-nulth culture

The display at Bill Reid Gallery pays homage to the c̓išaaʔatḥ artist and his impact on future generations

During the Potlatch Ban, c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht) artist George Clutesi would give his paintings to relatives as a way to ensure they stayed in community.

Many of his paintings remained with family on “Vancouver Island,” but for the first time, a collection is premiering on the mainland in downtown “Vancouver.”

As you enter the Bill Reid Gallery, a jumble of frames of every size and colour contour the walls, each guarding a sacred story told in bold Nuu-chah-nulth style.

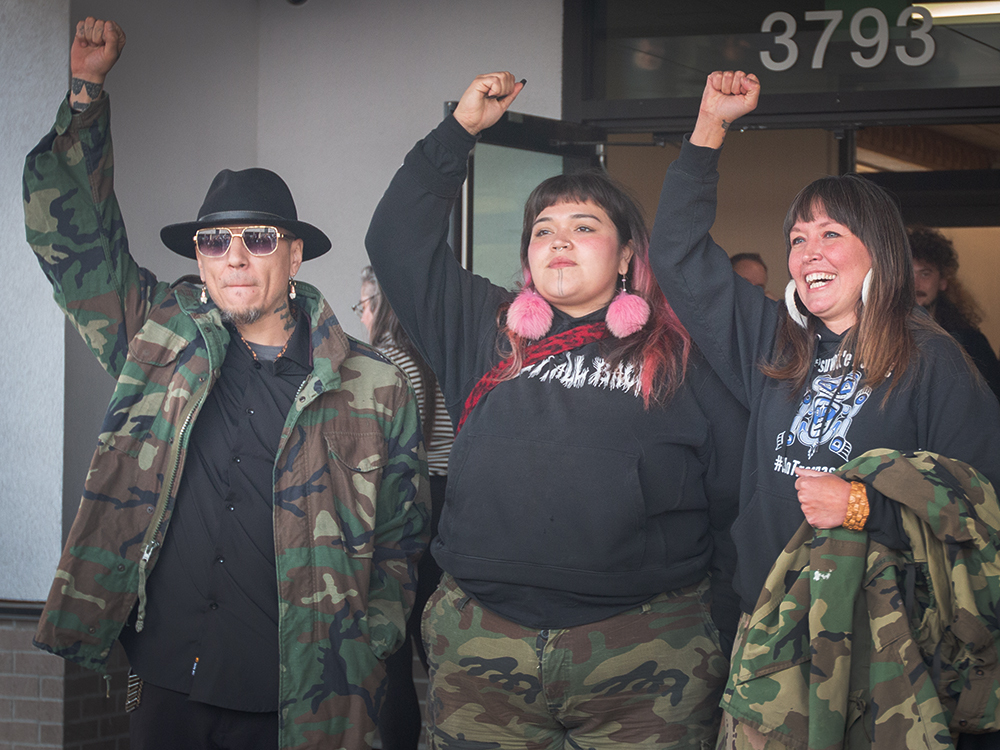

Combined, a bigger story is revealed, that of protection, will, and generosity. “ḥašaḥʔap / ʔaapḥii / ʕc̓ik / ḥaaʔaksuqƛ / ʔiiḥmisʔap” is a retrospective exhibition of 45 works of the prolific artist, writer and trailblazer.

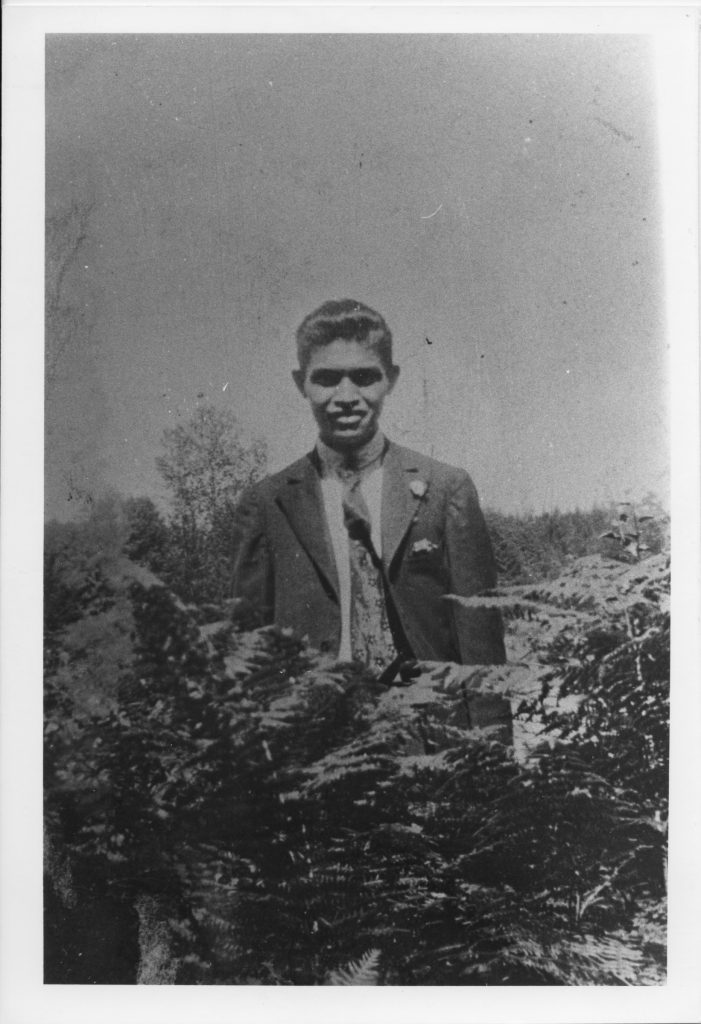

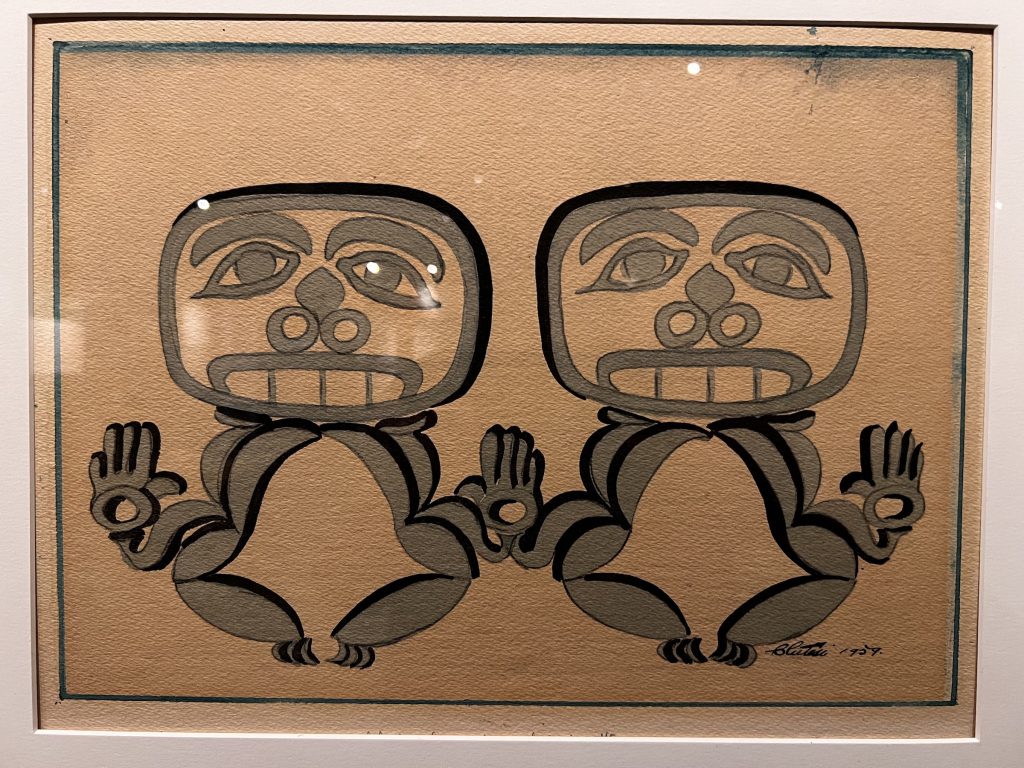

Walking through the exhibition, paintings, drawings, books, and new works from the next generation of Clutesi-inspired Nuu-chah-nulth artists propel the viewer through his life history. Born in 1905, Clutesi revived — and mastered — Nuu-chah-nulth form from the 1940s to the 1980s.

Clutesi was born in maaktii (Port Alberni), and grew up in a large, traditional Nuu-chah-nulth family.

He survived a decade in the Alberni Indian Residential School (AIRS), and managed to hold on to his identity and culture. Following a back injury in the logging industry, Clutesi returned to AIRS as a custodian.

He saw the job as an opportunity to watch over and encourage the children to practice their language and retain their identities. In doing so, he became an informal cultural councillor for the children — all in secret — hiding bundles of food, sharing stories and hugs.

A 40-minute documentary by Tsawout filmmaker Dano Underwood invites visitors to hear memories of Clutesi from seven of the survivors he shielded. It’s the first time their stories have been shared in a public setting.

“He just reminded us all the time, ‘Know who you are, where you’re from, who your family are. Never forget,’ and I’ve never forgotten,” said Mark Atleo in the documentary, which will soon be available to watch online.

Even the name of the exhibition, written in the Tseshaht language, honours Clutesi’s protective nature, among other celebrated traits: ḥašaḥʔap (keep, protective) / ʔaapḥii (generous) / ʕac̓ik (talented) / ḥaaʔaksuqƛ (strong willed) / ʔiiḥmisʔap (treasure).

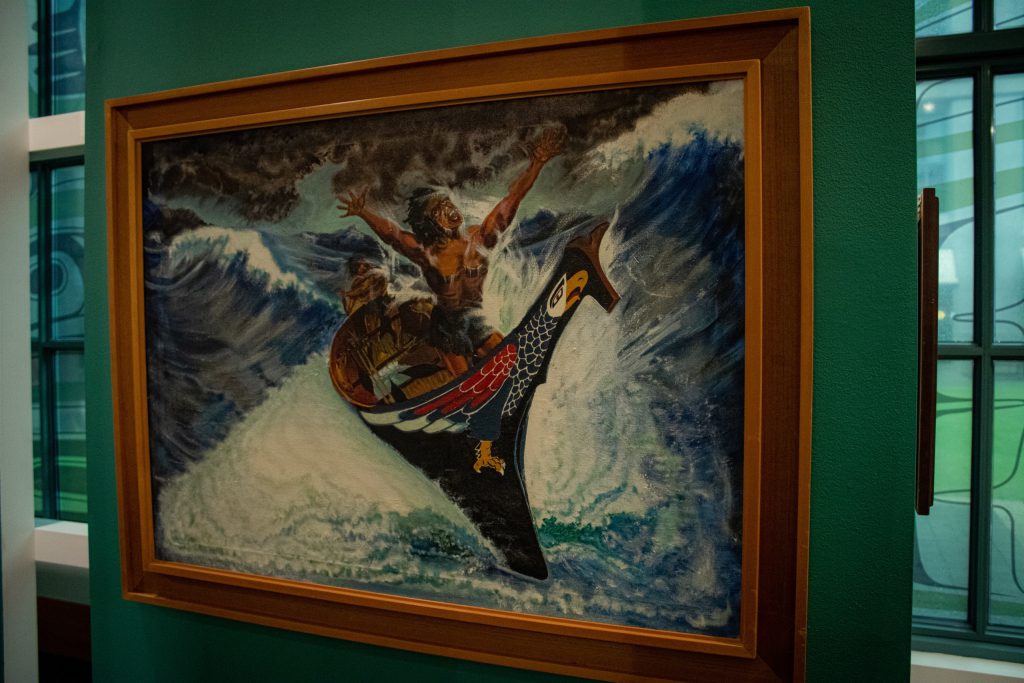

From watercolours, to printmaking, to drawing and sketches, Clutesi’s diversity in medium and style is unique and striking. At one point, viewers are confronted with the realism of oil on canvas — a cedar canoe looks like it’s about to burst through the wall and take you out. As you duck to the side, you’re met with the safety of a “simple” pen and ink line drawing of a whale.

Though dramatically dissimilar to the untrained eye, Clutesi braids Nuu-chah-nulth culture and story throughout each of his works. From wolves and whales to rain dance frogs, ceremonial references are everywhere you turn.

Clutesi’s advocacy for Nuu-chah-nulth storytelling didn’t end in the visual arts. A frequent contributor to the Indigenous newspaper Native Voice, and CBC Radio, Cluesti would share Nuu-chah-nulth stories for readers and listeners of all ages.

“All my paintings will be devoted to the past life of my own people … their mode of hunting, their love of the sea, and some of their dances and plays,” said Clutesi in a 1959 newspaper report. “I know the history behind these paintings and they all mean something to us.”

In 1949, Clutesi hitchhiked from “Port Alberni” to “Victoria” to give testimony to the Royal Commission on the National Development of the Arts, Letters and Sciences, about the federal government lifting the Potlatch Ban.

“I have tried to put on canvas what my people lived for, what they accomplished, the dances they created and so forth,” said Clutesi in his testimony to the Royal Commission. “It is an art that has been almost entirely forgotten, and if it isn’t revived or preserved, it will be forgotten altogether.”

He was told by the Royal Commission to go home and sing, so he did, forming the first dance group since the Potlatch Ban was implemented in 1885.

In the centre of the gallery, a large wall filled with newspaper clippings celebrates the scope of Clutesi’s many accolades. Headlines like, “Clutesi Rescues Potlatch from Oblivion,” “Involving the Elders in Education” and “Another Outstanding Book by George Clutesi’ — offers a glimpse of how widely cherished he was.

One accomplishment he was particularly proud of was being awarded a Doctorate of Laws from the University of Victoria in 1971. His ability to cross-pollinate between disciplines at such a high level is part of what makes Clutesi so influential.

Visitors are graced with works from six additional Nuu-chah-nulth artists and scholars, who were invited to contribute new work based on their engagement with Clutesi’s art and writing.

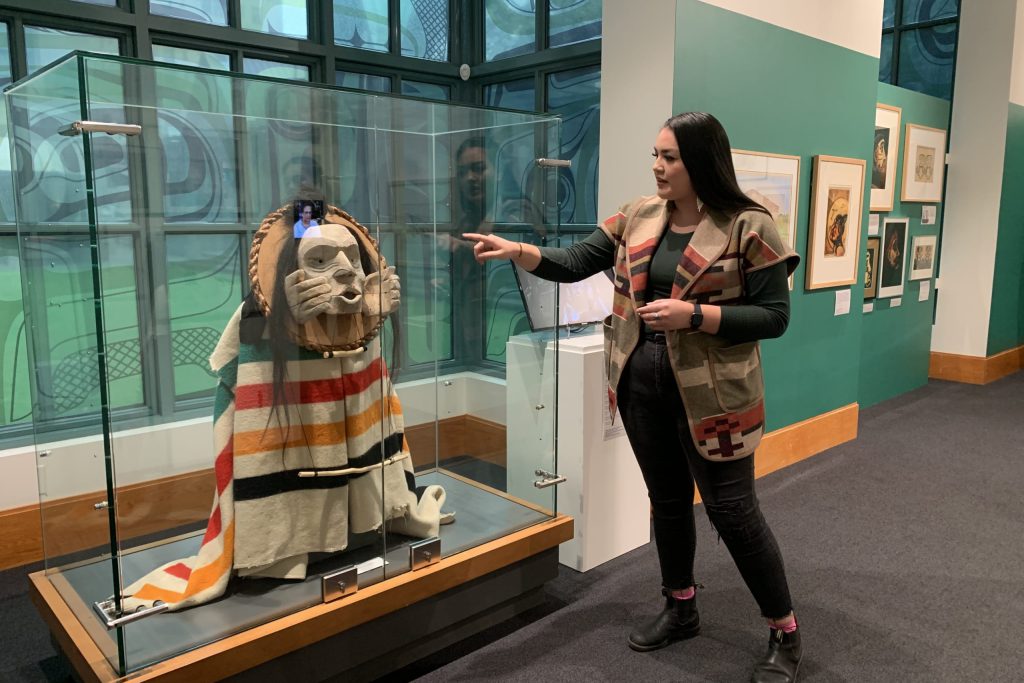

A ghostly open-mouthed red cedar healing mask, dotted with smallpox-red paint sits on top of a Hudson’s Bay blanket. When brothers Timmy Masso and Hjalmer Wenstob (Tla-o-quiaht) were separated during the pandemic, they reflected on the smallpox epidemic and wanted to create a monument to remember both seemingly unimaginable events. Their monument, the Healing Mask, was worn during a ceremonial dance at the exhibition opening, with many of Clutesi’s family in attendance.

Marika Echachis Swan, another Tla-o-quiaht artist, draws from Clutesi’s trait as a protector.

“Becoming a mother has been the most transformative and powerful experience of my life,” says Swan in the written description of her artwork, Weaving A Place of Safety.

“Fastidious braids fall gently and firmly, creating a warm den for cuddles to be enjoyed,” her statement adds. “We celebrate our efforts because we know that each tender moment shared is a testament to all the work and discipline it has taken to defend a space safe enough for intimacy to bloom.”

The exhibition also includes inspired works by Petrina Dezall (Mowachaht/Muchalaht), Dr. Dawn Smith (Ehattesaht) and Dr. Tommy Happynook (Huu-ay-aht).

Aliya Boubard and Beth Carter, the Bill Reid Gallery’s curators, each noted that Clutesi and Bill Reid led similar lives in some ways. Both prominent Northwest Coast First Nations artists of the twentieth century, the two contemporaries exhibited their talents using an array of mediums with similar aims: to celebrate the stories of their people.

“Like Bill Reid … George Clutesi was a huge inspiration for the next generation of Nuu-chah-nulth artists and scholars,” said Boubard in a statement.

“While they had very different life experiences and approaches to their art forms, these artists helped raise awareness both inside and outside of their communities. George has been instrumental in not only educating others about his community’s cultural traditions, but preserving the sacred stories, dances, and masks that are practiced and celebrated today.”

“George Clutesi: ḥašaḥʔap / ʔaapḥii / ʕc̓ik / ḥaaʔaksuqƛ / ʔiiḥmisʔap” is on view at the Bill Reid Gallery until January 19, 2025.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Youth connect to their lands — and relatives — with annual Rez Ride

The Menmen tl’a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh mountain bike team pedals through ancestral villages — guided by Elders, culture and community spirit

-

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests