After four-year negotiation, Sts’ailes reaches child welfare agreement with ‘B.C.’ and ‘Canada’

Grand Chief William Charlie says it was a relief to wrap up the often ‘emotional, frustrating, disappointing’ process, originally slated to take one year

After wrapping up a long and sometimes frustrating four years of talks to regain child welfare rights in his community, Sts’ailes Grand Chief William Charlie felt a weight lift off his shoulders.

“People have told me I look much better this week,” Charlie, who is chief executive officer of Sts’ailes First Nation, told IndigiNews in an interview earlier this month.

On Sept. 3, Sts’ailes signed a co-ordination agreement with “Canada” and “British Columbia,” supporting the First Nation’s inherent rights to care for its children and families through its own law — Snowoyelh te Emi:melh te Sts’ailes.

Siyam te Sts’ailes (Sts’ailes leadership) signed the agreement along with Patty Hajdu, federal minister of Indigenous Services, and Grace Lore, the province’s minister of Children and Family Development.

The signing, which took place in Sts’ailes Xa’xa Temexw, was hailed as a historic moment for Sts’ailes, in particular because of the effort it took to get there.

“It was really emotional, frustrating, disappointing,” Charlie said in a phone interview.

The process, he explained, was meant to take just one year — but ended up totalling more than four years by the time the agreement was signed.

“At night, I would go home and think, ‘Jeez, what’s going on?’” he said. “‘Why are these people so hard to work with, and why is it so bureaucratic?’”

Last January, “Canada” withdrew from its commitment to sign a coordination agreement by a February deadline, offering no timeline or explanation.

But despite the federal withdrawal, Sts’ailes held a ceremony and signed an agreement with the province alone.

Once that bilateral agreement was signed, Charlie said Canada came back to the table to continue negotiations until this month when all three governments signed a deal.

“We were working with Canada right up until the signing date to come to some terms,” he said.

In a statement, Patty Hajdu, federal Minister of Indigenous Services, admitted child and family services are “something that rightfully belonged to (Sts’ailes) all along.”

“With the signing of this coordination agreement, Sts’ailes children and families will grow up immersed in their culture and traditional knowledge, supported by their communities,” she said.

“This is crucial for them to have a fair chance to succeed and for all of us to move forward on the path to reconciliation.”

The province’s Minister of Children and Family Development Grace Lore added the latest signing was “a pivotal step in our journey with Sts’ailes.”

The agreement comes at a time where other Indigenous communities are negotiating their own child welfare agreements, all in accordance with the federal Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, Youth and families, and the B.C. Child, Family and Community Service Act.

Last Thursday, the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Nations on northern “Vancouver Island” celebrated regaining their own child welfare jurisdiction, again with Lore and Hajdu in attendance. “No matter where I am, I will continue to fight for self-determination, for language, culture, children,” Hadju said at a Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw ceremony in “Port Hardy.”

“It’s important work and I’m so grateful to be doing it for you,” she said.

‘How do we get to our children?’

In a press release, Charlie stated “Snowoyelh te Emi:melh te Sts’ailes will blanket Sts’ailes people with love and protection like a swoqwe’lh (sacred wool blanket) while providing culturally relevant services.”

But not everything Sts’ailes sought in the talks was negotiated successfully; two issues remain which the federal government won’t agree to fund beyond two years, Charlie said.

He said the first outstanding issue that “Canada” doesn’t want to fund longterm is post-majority services, which deal with Youth aging out of care, for Youth living off-reserve.

“Ottawa” argued those services are the provinces’ responsibility. But historically under colonial rules, post-majority services have been funded through a mix of provincial and federal funding in cases where Youth live outside their communities.

Secondly, he said, “Canada” doesn’t want to commit ongoing funding to more costly high-needs cases.

Charlie said there are three Sts’ailes children whose care costs more than $16,000 per month, a sum he said Sts’ailes can’t manage alone.

For both the post-majority services and high needs cases, the federal government agreed to fund Sts’ailes for two years. The parties are slated to meet again in 18 months to review the agreement’s terms.

“Canada” has committed to providing nearly $119 million to Sts’ailes over the almost ten years, while the province has pledged more than $16 million, both subject to adjustments for inflation and population growth.

The new agreement comes nearly four years after Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised more than $542 million to help First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities set up their own child and family services.

Between 2021 and 2022, additional federal investments totaled more than $160 million. Last year, “Ottawa” budgeted an additional $1.8 billion to support communities over the next 11 years.

Sts’ailes has secured additional funding for capital expenses, such as upgrading its current services facility, building a new delivery building and additional resource homes — where residents learn traditional parenting and life skills from Sts’ailes staff and social workers — as well as buying needed new vehicles.

“It sounds small, but it’s big for us because of where we’re situated — how do we get to our children?” Charlie said. “How do we go and start to meet with them?”

Sts’ailes already has a mother and two children living in one of the newly built resource homes. Before the build was complete, the family were living in a hotel.

“We had no real place for her,” said Charlie. “It’s one thing going into a hotel on holidays or something, but to live in there with two children, that was difficult.”

Charlie said that, with the agreement now in place, the community’s priority is to hire more staff. In the past, he said, the First Nation had to operate on a shoestring budget — improvising and compromising on how it delivered services, and underpaying staff who faced already-excessive workloads.

“So we really need to staff up,” he said.

Often when Sts’ailes hires a new social worker, Charlie said the first thing they have to do is spend time “de-programming and then re-programming them” on how to work with First Nations.

“(The colonial) system has never really worked for us,” he said. “How do we change their vision and style to do work in a Snowoyelh (Sts’ailes traditional laws) way?”

‘We need to be able to keep the family together’

Charlie said that part of the “re-programming” that’s been necessary is to train the social workers to respond more quickly to create a care plan for a child.

MCFD allows this process to take two weeks, but Charlie said Sts’ailes aims for 24 hours. The First Nation’s approach to engaging with families is also more inclusive, he added.

Whereas MCFD likes to interview each family member in isolation when a child’s safety is in question, Charlie said the Sts’ailes approach is to “work with the whole family” to determine the best care plan and support them to achieve it.

“(MCFD’s) idea is to take the child out of the family,” he said. “That’s not what we want … We need to be able to keep the family together.”

When IndigiNews spoke to Charlie, he’d spent the previous night in “Vancouver” with his staff for several days of training. He said they were reflecting on the momentous moment they were in, while looking ahead with trepidation.

He said many at the training shared that they were nervous about what’s to come under the First Nation’s agreement — but he replied that re-gaining authority over child welfare “is a good problem” to have after decades of having “no influence or say in the solution.”

“Now we have some say,” he said, “and we have some resources to address the issue and start again.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

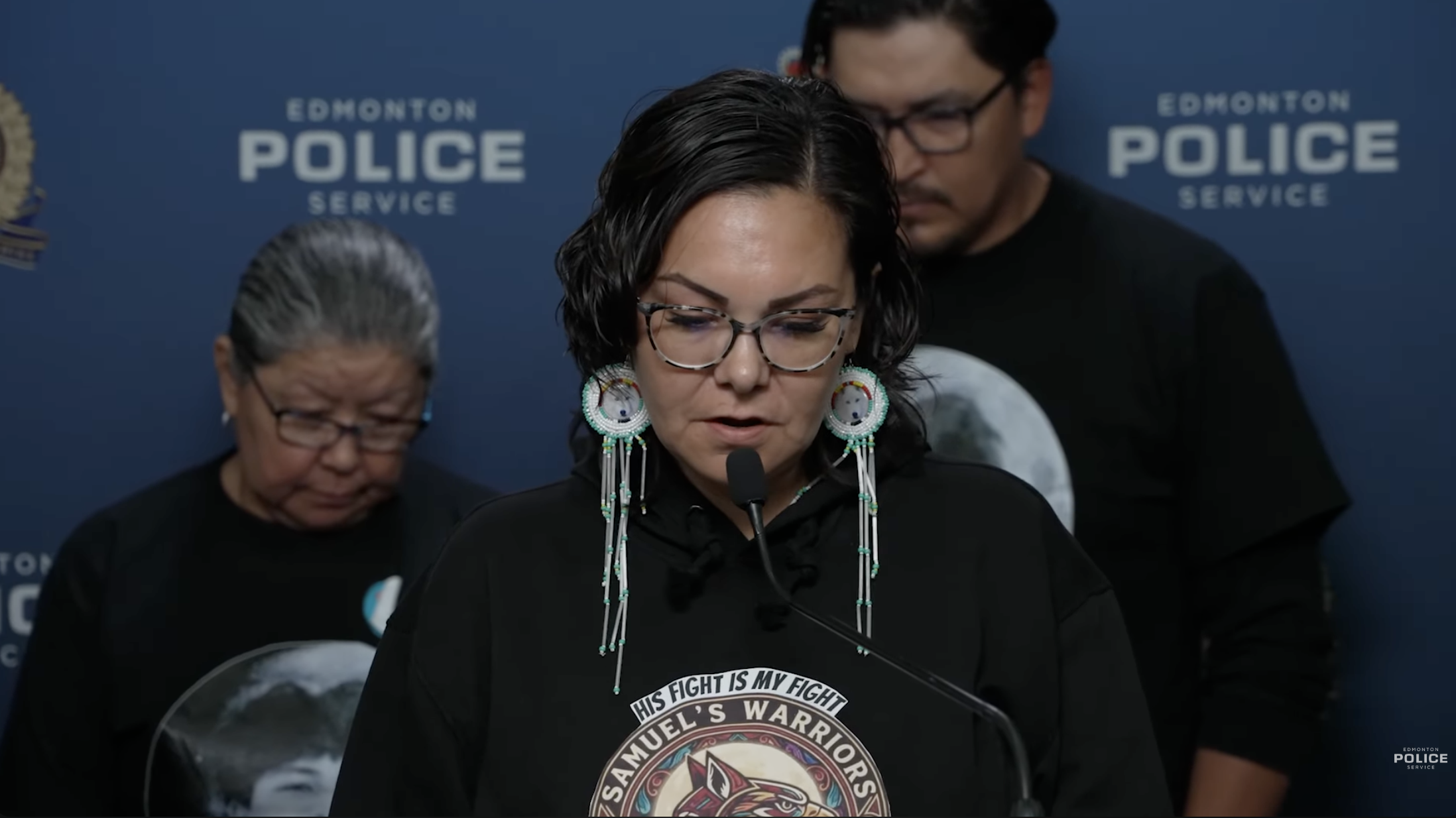

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death

-

Book remembers ‘fighting spirit’ of Gino Odjick, hockey’s ‘Algonquin Assassin’

Biography of late Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg left winger explores Odjick’s legacy as enforcer in the rink — and Youth role model off the ice