‘No trust’: Neskonlith members seek answers as tensions climb amid firings, lawsuit

Indigenous Services confirms complaint filed, as Secwépemc community embroiled in allegations of election fraud, ‘civil conspiracy’

Members of Neskonlith Indian Band are becoming increasingly frustrated with their leaders, after a councillor was removed from office over alleged election fraud and two staff people were fired.

Lawyers for Neskonlith’s chief and council say the band removed an unidentified councillor “alleged to have engaged in election fraud” during the community’s last elections in 2023.

The tensions are about more than an election, however — as a series of controversies have fuelled mistrust between the First Nation’s voters and those they elected to office nearly three years ago.

The dismissals and allegations have sparked a lawsuit, transparency concerns, and a formal complaint to “Canada” over alleged financial mismanagement.

Tensions within the 697-member Secwépemc community erupted during an emergency community meeting in February. At the event, shouting and insults broke out between residents and their chief, according to a privately recorded video obtained by IndigiNews.

Some members of the small First Nation near “Chase, B.C.” are demanding accountability and answers about their leaders’ decision-making on a wide range of issues — including questions about the band’s economic development corporation, Sk’atsin Resources.

The federal government confirmed it has received a formal complaint “regarding the misuse of public funds” in the First Nation, and that all such allegations are “examined properly” and, if warranted, met with “appropriate action.”

Neskonlith member Jennifer Dick told IndigiNews many of the concerns from community members relate to “finances, transparency” and a lack of accountability.

“Over and over again, whenever we bring [concerns] up with the council, they don’t do anything,” said Dick.

“It just seems like we’re wasting energy trying to point out things to them, and nothing will come out of it.”

Dick alleged numerous questions from community members about Neskonlith governance go “unanswered and ignored” by chief and council — whether about the firings, to how its company operates, as well as faulty water systems, food sovereignty, housing, fire issues and more.

‘Committed to ongoing transparency’

Neskonlith Kukpi7 (Chief) Irvin Wai did not respond to requests for comment. IndigiNews received an email from a “Kamloops” law firm representing the First Nation.

“Chief and council remain committed to ongoing transparency and to improving outcomes for the band and all of its members,” wrote Lukas Kozak, of Forward Law.

Neskonlith Indian Band is led by five councillors and Wai, who took office after elections on Jan. 26, 2023, ending a 16-year-tenure held by his predecessor, Judy Wilson.

The band’s first annual general meeting after the election, on Nov. 30, 2023, was advertised with the theme “Hitting the reset button.”

That election brought three new faces to the band council — Frances Narcisse, Mindy Dick and Shirley Anderson — and re-elected Michael Arnouse and Joan Manuel-Hooper.

But only four of those five councillors are now listed on the band’s official website — with Narcisse’s name absent.

Neither the First Nation nor Narcisse would confirm whether she was the person removed from her council position.

“None of the current chief and council members were implicated in the election fraud alleged to have taken place,” Kozak wrote.

‘Chief and council and Neskonlith staff investigations’

Community anger boiled over on Feb. 28, when leaders held an “emergency community engagement” meeting in Salmon Arm “regarding chief and council and Neskonlith staff investigations.”

Paquette and Associates Lawyers gave a presentation “for band members only,” according to a post on the band’s Facebook page.

IndigiNews obtained video from the tense emergency meeting, when an external investigator revealed a member who ran for council in the 2023 election owed the band money at the time — in violation of Neskonlith’s election code.

“That individual had to have known that that individual was not eligible to run in the election,” the investigator said, “because that person knew that they had a debt and they acknowledged that debt in prior years.”

At the meeting, the investigator told attendees that Neskonlith’s financial manager is expected to give chief and council a list of debts owed to the band before every election; the chief could then choose whether to write-off any debts owed.

But no list of debts was ever submitted by the financial manager, the investigator said, nor were any debts expunged.

“The individuals involved decided that they would just delete or remove the debt from the records of the band,” the investigator told the gathering.

IndigiNews asked Neskonlith’s lawyers if the financial manager faced any repercussions for failing to submit a list of debts, but received no response.

The federal First Nations Financial Transparency Act requires bands to make their audited financial statements, salaries and expenses available to their communities online.

IndigiNews could not find any such financial documents online for either 2023 or 2024.

Financial statements are, however, available for the First Nation’s development corporation, Sk’atsin Resources.

Those documents suggest the two parties together generated more than $1.2 million in revenue in the 2023-2024 fiscal year, according to public financial statements. It was a marked increase from just under $165,000 the year before.

While revenues grew more than sevenfold in a year, Sk’atsin’s expenses nearly doubled to $4.3 million, while salaries increased by $1.4 million.

“I don’t see any social, economic benefits coming to the people,” said Dick, who said that “band members have 99 per cent” ownership of Sk’atsin’s shares.

“However, the band members don’t have any say in it.”

Indigenous Services Canada confirmed in an email to IndigiNews on Sept. 18 that it “received an allegation related to Neskonlith community,” but the department could not comment further on the nature of the complaint due to privacy concerns.

“We take allegations and complaints regarding the misuse of public funds very seriously,” said department spokesperson Maryéva Métellus in an email.

“To that end, the department has a process to ensure allegations and complaints are examined properly and that appropriate action is taken.”

Band alleges ‘civil conspiracy’: lawsuit

Neskonlith Indian Band’s former interim executive director Evelyn (Fay) Ginther said she was the one who sparked the investigation of alleged election fraud. But she alleged she was fired last October as a result, along with another employee, Kyle Wright.

In an April 7 filing to the B.C. Supreme Court, the Neskonlith member and two-term councillor from 2015 to 2023 said “one councillor was recently removed from office following the results of an investigation that Ms. Ginther helped to initiate pursuant to her duties as interim executive director.”

At the February community meeting, Ginther told attendees she was being sued by Neskonlith chief and council, allegedly for “holding your guys’ feet to the fire,” she said in a video recording.

“You should be ashamed of yourselves,” Ginther said at the meeting. “Talk to the people.”

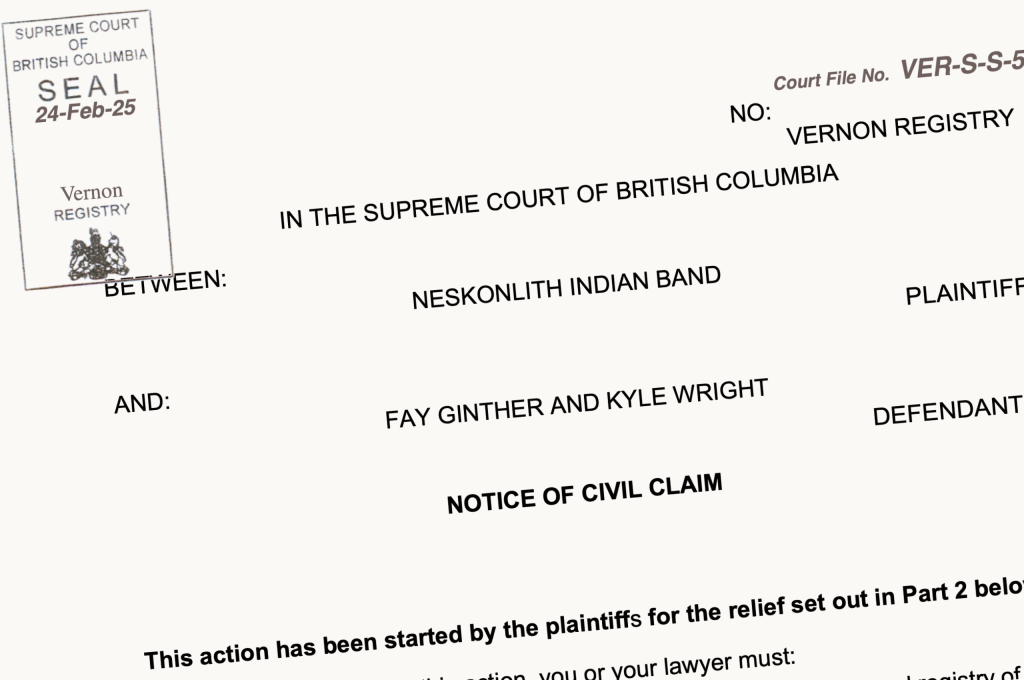

That same month, the First Nation filed a civil claim against Ginther and Wright, alleging they committed a “civil conspiracy” against the band.

The lawsuit also alleges the pair “breached their employment agreements” and “their fiduciary duties,” and were also “enriched” at the First Nation’s expense.

Neskonlith Indian Band court filings allege the two “combined or conspired with one another with intent to injure Neskonlith by entering into an agreement to isolate and undermine the lawful authority of chief and council to properly govern Neskonlith.”

‘No factual or legal basis’ to accusations: defendants

In their responses to the First Nation’s lawsuit, Ginther and Wright both said many of the allegations in the civil claim are “known to be untrue” by Neskonlith Indian Band.

The pair insist there’s “no factual or legal basis” for accusations they committed a “conspiracy, breached the employment agreement with the plaintiff, breached her fiduciary duties to the plaintiff, or was unjustly enriched at the deprivation of the plaintiffs.”

Ginther maintains she “acted in accordance” with her responsibilities as interim executive director regarding the investigation that led to the councillor’s removal, which occurred after she was fired.

Wright alleges in his response he was “wrongfully terminated,” denying that he “combined or conspired with Ms. Ginther as alleged or at all to injure the band.”

Wright had served as the IT manager for the band from October 2023 until his firing a year later, and also took on additional responsibilities as interim human rights manager until March 2024, according to his response to the civil claim.

Neskonlith’s governance policy, cited in the band’s court filings, stipulates what happens “if the chief or a councillor is alleged to have breached any of their duties or failed to carry out their responsibilities to the requisite standards set out in this policy.”

According to that policy, it is the executive director’s job to “investigate the allegations,” or hire an external investigator to do so.

“I served this community for years; I love this community,” Ginther said during the February community meeting.

“I did my best in there, I helped out the community … Don’t look at me like that and say that I did some things wrong — I didn’t.”

She reiterated that she was “following policy and procedure” by helping initiate the investigation — something she said she intends to prove before a judge.

“I have to pull out my pension to go in court,” she said. “How does that sit with you?

“I’m the one that was helping the people out.”

Leadership ‘became increasingly concerned’

At the Feb. 28 meeting, Kukpi7 Wai told participants “this council has nothing to do with the investigation.”

And, he added, the community is only hearing “one side of the story.”

“Once the truth comes out, you’ll understand why we did this with chief and council,” he said. “We have a fiduciary duty.

“We have to protect you all. The truth will come out when the investigation’s over.”

In an email to IndigiNews, Neskonlith’s lawyer Kozak said chief and council deny Ginther was fired for investigating the alleged election fraud, nor that the band’s lawsuit against Ginther “arose from any such investigation.”

“Both the matter involving the former executive director and the matter involving the individual alleged to have engaged in election fraud are currently before the court,” Kozak wrote.

“Chief and council are committed to seeing these matters resolved in open court, where all parties’ evidence can be presented publicly and tested.”

The band’s lawsuit states Ginther “had effective control over Neskonlith’s finance department,” and that she and Wright together “had effective control over Neskonlith’s HR department, including the ability to hire and fire staff and contractors.”

In August 2023, after being promoted to interim executive director, the civil claim alleges Ginther acted “on her own initiative” to hire Wright as IT manager, and two months later as interim HR manager.

That, according to the civil claim, gave him “effective control over Neskonlith’s IT systems, including all emails and Neskonlith’s IT hardware” between October 2023 to October 2024 — alleging he “viewed and monitored the emails of employees of Neskonlith as well as those of chief and council.”

The lawsuit alleges that by “using their control of systems,” Ginther and Wright acted “to benefit themselves personally and without detection or objection on the part of chief and council.”

The band also alleges the pair “attempted to intimidate” chief and council and other employees, creating “a climate of fear” by using the band’s resources “to try and harm Neskonlith.”

“On multiple occasions … the defendants threatened members of chief and council with investigations and possible lawsuits for purported breaches of the policy,” the lawsuit states.

The claim also accuses Ginther of authorizing additional invoices for work performed by Astra Computer Services — Wright’s own computer business — allegedly enabling “double-dipping” into band funds.

Wright denied the allegations, including any unauthorized monitoring of emails for staff, chief or councillors, and said he didn’t have “effective control” over the band’s IT systems.

He also denied “double dipping” into band funds, saying additional payments reflected work done on a project to create the website template, which he said had been authorized by the previous executive director.

“This work was often performed by Mr. Wright after regular work hours and in addition to his duties as the IT Manager and Interim HR Manager,” his response states.

Ginther and Wright both denied they held “effective control” over the HR department, nor any ability to “to hire and fire staff and contractors,” noting that process is dictated by Neskonlith policies.

Ginther further denied she or Wright controlled the band’s finances, arguing the finance department has its own director and employees, and she never had the power to authorize payments.

On Oct. 7, 2024 — four days before Wright was fired — “a quorum of council” determined it was in the band’s “best interest” to terminate his contract, after they “became increasingly concerned” that he was “attempting to intimidate and control them and was not performing his duties effectively and efficiently.”

‘Build a case against chief and council’

Three days after Wright’s firing, the First Nation alleges Ginther let him return to Neskonlith offices to “access the band’s IT systems” — something that she denied.

The band alleges that Ginther then “used Neskonlith’s funds” to source services from the band’s contracted HR consultant “in order to try and build a case against chief and council.”

According to the lawsuit, the HR consultant then “collaborated and made changes” to a demand letter to chief and council that Ginther had written.

The band’s civil claim alleges that on Oct. 15, 2024 — three days before Ginther was fired — she or Wright arranged a meeting between all band managers and the HR consultant.

The lawsuit alleges this meeting’s “participants discussed ways to undermine chief and council,” for instance taking sick leave.

Afterwards, the band said three of the meeting participants notified Neskonlith they were taking indefinite medical absences.

Neskonlith terminated Ginther’s employment contract on Oct. 18, but at the time did not state her firing was for “just cause.”

“However,” the lawsuit states, “based on the facts discovered by Neskonlith post-termination … Neskonlith now relies upon the doctrine of after-acquired cause.”

Even though both Ginther and Wright’s employment contracts were terminated last October, the band alleges that Wright — acting under Ginther’s instruction — hired Ginther’s husband for the role of housing manager at Neskonlith in December 2024.

Economic development company sparks scrutiny

Concerns among community members pre-date the string of recent dismissals and lawsuits, however.

The First Nation’s economic development company, Sk’atsin Resources, has drawn scrutiny as well for a series of controversial projects on reserve.

Some Neskonlith members are asking how funds from the company — which is 99 per cent owned by the band — are being handled. Several allege there’s no transparency about how Sk’atsin’s money is being spent.

Public financial documents from Sk’atsin Resources show the business’s net income has dropped, while expenses have climbed, since a new chief operating officer (COO) took the helm around two years ago.

Neskonlith member Dick is among those concerned about where the funds are going. She alleged COO Gary Gray — who residents say is not a member of the First Nation — is making high-stakes business decisions without community consent, and cultivating what she sees as an “industrial complex” environment on the reserve.

“They’re spending a lot of money, and not being transparent,” said Dick.

IndigiNews tried to contact Gray for comment through multiple channels since Aug. 12, including emails to Sk’atsin Resources and his personal company, GrayCo, and by telephone and voicemail. He did not respond by time of publication.

Before filling the position sometime in 2023, Gray and his company, Grayco Contracting, had partnered with Sk’atsin Resources on several contracts such as wildfire fighting, according to a social media advertisement in 2021.

The company’s 2023-24 financial statement shows that the Sk’atsin paid $171,654 for unspecified services to Gray’s own Grayco Contracting — no such payments were issued by Sk’atsin to Grayco the year before, before Gray was in the role.

In Gray’s first year, Sk’atsin amassed a long-term debt of $1 million, significantly more than the nearly $56,000 the year prior. Its cash flow dropped by more than $2 million, too.

Sk’atsin also spent more than $8,000 in meals and entertainment, the documents reveal.

“It’s all really self-serving — building up all these offices, purchasing all kinds of equipment,” said Dick.

She described trucks and other equipment strewn around the community, connected to a series of resource and infrastructure projects that sparked outrage from some residents.

“What Sk’atsin has done in this community was made an industrial complex or site right in our front yards, and we didn’t approve it,” said Dick.

“There’s gas cans laying all over, they dump trucks here and there. There hasn’t been any permission to do that.”

In the past two years under Gray’s leadership, Sk’atsin Resources has been the subject of three “non-compliance enforcement actions” under the B.C. Wildfire Act, for the use of “fire against regulations.”

The most recent enforcement action was on May 8; and two a year earlier, both on May 10, 2024.

When IndigiNews asked Neskonlith leaders who is on Sk’atsin’s board of directors, and about concerns raised around the company, Forward Law replied on the band’s behalf.

“This matter too remains before the court,” lawyer Kozak wrote in an email.

“As such, chief and council will provide no further comment at this time and remains committed to seeing both matters through to their conclusion in the inherently open and transparent public courts system.”

Paving project ‘sensationalized by a small group’

Last May, Gray and Sk’atsin spearheaded a recycled asphalt repaving project throughout Neskonlith’s reserve roads.

The project drew outcry and condemnation from several band members, who raised fears about health impacts of using recycled highway asphalt.

Several members said the community was not made aware of the use of the material beforehand.

In a letter posted to Sk’atsin Resources website in May 2024, Gray apologized for communications about the paving work, but insisted there was no health risk from the paving material, which he said had been “sensationalized by a small group opposing the project as toxic tailings.”

“We regret that some members feel that the project and the information could have been communicated and executed better to the Neskonlith community,” he wrote, “and for that we are truly sorry and intend to do better in the future.”

In the same letter, Gray called out “threats, damaging equipment, paint spread, mischief and assaults occurring from Neskonlith Elders, members and non-members” over the paving project, “causing discontent and disrespecting Neskonlith community members.”

Gray and another worker were allegedly assaulted by a band member who opposed the project, with the case going before the courts earlier this month.

Later that year, three Neskonlith-affiliated companies were registered on the same day. Gray and Sk’atsin Resources bid on a BC Hydro “clean or renewable resources” initiative, proposing 57 Neskonlith-owned wind turbines.

The bid failed. But a letter from BC Hydro lists the costs just to apply as including $43,000 in proposal fees and non-refundable deposits.

“That’s a lot of money to waste,” Dick said. “It wasn’t approved by the band members … Sk’atsin is just doing their own thing.

“The people weren’t consulted about going into a wind power project — no one even knew about it.”

‘No trust between community’ and leadership

Just 15 months after Neskonlith’s new leaders held their “hitting the reset button” AGM, community anger boiled over across a range of issues in the First Nation.

At February’s emergency meeting, one band member asked Wai and councillors for proof that due process had been followed — and that the proper “steps were followed in the right order” — in firing the employees.

“This is important when it comes to termination of employees — this is their livelihood,” said the member, who IndigiNews was unable to identify.

“The system here is failing us. Time and time again, I hear [of] letters being sent, emails being written — people standing up — and nothing.”

She alleged there’s a particular lack of respect shown towards women in the community, especially at meetings, where she said women “just aren’t taken seriously.”

That’s a concern shared by Dick, as Neskonlith women are at the forefront demanding answers on a wide range of governance issues.

Another band member at the meeting called on the chief and council to be much more “transparent to this community,” expressing feeling “ignored” by her leaders.

“It might sound like we’re yelling, but we’re not,” she said. “There’s a lot of concerns coming up now with this, because a lot of us didn’t know about this,” she said, referring to the alleged election fraud.

“That’s why there’s no trust between the community and chief and council, because there’s decisions being made for us.”

She then urged the chief to “hear us, not react.”

“This is what the community needs, is to not just hear what we have to say but actually listen,” she said. “Without sounding angry, without being defensive. Every single meeting I go to, you get defensive.

“What we are doing here is to hold each of you accountable, not talking down on you … when you’re doing something that is not right.”

Wai then interjected, telling the community member, “I won’t stand here and be bullied.”

His comments drew a swift reaction from the crowd, with someone calling Wai’s reaction “intimidation tactics.”

“Exactly what she’s talking about,” a band member said.

The room quickly descended into shouts of “shut up” between some members and their leadership.

Wai then apologized for “getting angry,” saying he only raised his voice because of concern for his community.

“I do really care about my people, I do get passionate, and I do get loud,” he said.

“We can either work together and try, or you can move on with another government in a couple of years and try again.”

It’s “a lonely thing” being chief, he continued.

“My wife is tired of me crying. I cry because I care, not because I’m frustrated,” he said.

“I’m not ashamed of what I’ve done. I work hard, I look after my family, I look after my community. And I’ll continue to do that.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

‘No trust’: Neskonlith members seek answers as tensions climb amid firings, lawsuit

Indigenous Services confirms complaint filed, as Secwépemc community embroiled in allegations of election fraud, ‘civil conspiracy’

-

shíshálh Nation holds grad ceremony to recognize residential, day ‘school’ survivors

The event honoured the life experiences and strength of survivors, with about 50 people being presented with certificates and cedar caps: ‘We see you, and we see how hard you worked’