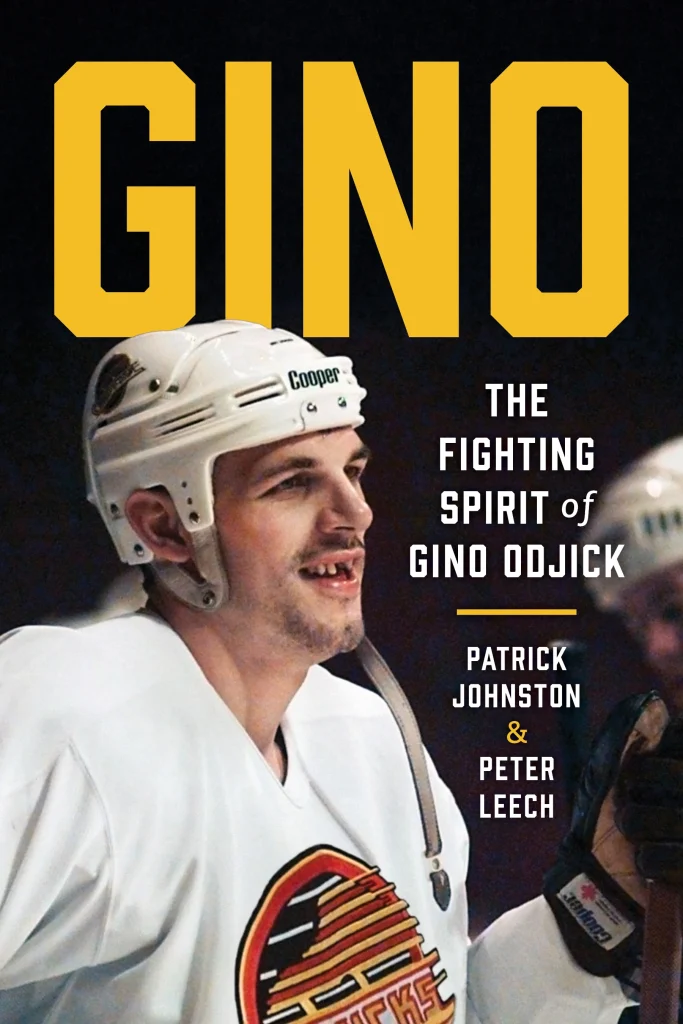

Book remembers ‘fighting spirit’ of Gino Odjick, hockey’s ‘Algonquin Assassin’

Biography of late Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg left winger explores Odjick’s legacy as enforcer in the rink — and Youth role model off the ice

Gino Odjick, the celebrated Algonquin hockey left winger from Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation who died nearly three years ago, is being remembered in a new biography.

Veteran sports journalist Patrick Johnston and Odjick’s friend Peter Leech co-wrote Gino: The fighting spirit of Gino Odjick, published last Tuesday by Greystone Books.

The author duo talked to the longtime Vancouver Canuck’s family members, former teammates, and others he inspired throughout his life — on and off the ice.

Odjick’s achievements were obvious to Johnston when he began covering the Canucks as a journalist with Postmedia.

“Truthfully for me, he became a story — someone I can understand from afar,” Johnston said in an interview.

Johnston said many of Odjick’s former teammates would light up at the chance to share their memories of him.

“This was someone that they loved,” Johnston said.

“This was a guy that meant everything to them, who had made their career better — not just on the ice, but as a human being.”

‘Fighting prowess,’ positive role model

In mid-2022, Odjick was inducted into B.C.’s Sports Hall of Fame, seven months before his Jan. 15, 2023 death — at age 52, of a heart attack — nearly a decade after being diagnosed with amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis, a rare terminal disease.

His “fighting prowess” as an enforcer earned him the nickname “Algonquin Assassin,” notes the website of the Indspire Awards, which honoured Odjick with its sports prize 10 years ago.

The connections he made with others followed him throughout his career — from growing up learning hockey from his father Joseph on his reserve’s outdoor rink, to playing eight seasons for the Vancouver Canucks, followed by stints with the New York Islanders, Philadelphia Flyers, and the Montreal Canadiens.

But Odjick’s Indspire Award also recognized his efforts after he retired from hockey in 2002 — after suffering a concussion which haunted him for decades — during which he “focused his energies on being a positive role model” for Indigenous Youth.

Many of his fans fondly remember Odjick’s energetic National Hockey League (NHL) debut — when he developed his reputation as a fearsome enforcer; his very first game saw him enter two fights in the rink. His fighting earned him 2,567 penalty minutes, and a Canucks penalty record still unbroken.

According to his league career stats, in the 605 games he played between 1990 until his retirement in 2002, Odjick scored 64 goals — 16 of them in a single season — and 73 assists.

His energy was described by many as magnetic, and throughout his decades-long career was recognized for his contributions both on and off the ice.

The book is not only a story about Odjick’s hockey career as an enforcer — a role that includes physically confronting opponents on the ice and defending teammates — but also about his trailblazing legacy for Indigenous players within the NHL more broadly.

‘He was a warrior’ on and off the ice

For co-author Leech, who is from St’át’imc Nation, collecting stories about his friend was an emotional process.

“It was tough at different times for me, because I was so close to him,” he told IndigiNews. “And then to hear the stories about him and the things he did, it kind of brings a smile and warm feeling.

“He was a warrior on the ice, but he was also a warrior off.”

In the book, Leech argues Odjick’s legacy should be seen in the context of the hockey league more broadly.

In one passage of Gino, the authors write: “In many ways Odjick’s arrival in the NHL heralded a new start for the Canucks,” the book declares. “For one, he was big: both in how he played and in character.”

In particular, the biography explores his “huge impact” on fellow Indigenous hockey players, Leech noted.

“He helped open the door for Indigenous players,” he said.

Although he earned a fearsome reputation in the game, Odjick also faced struggles during and after his long career.

He suffered from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a brain injury often linked to sports.

Head injuries in hockey are still prevalent today and Odjick — a fighter the B.C. Sports Hall of Fame says was known for “courageously protecting his teammates” — is just one of many players who have experienced them.

While Odjick received many physical injuries through his time playing hockey, Leech notes that his friend “would do it again without hesitation.”

To Indigenous Youth, Odjick ‘was kind of like medicine’

In a 2014 open letter revealing his terminal diagnosis — written with Leech’s help — he described his upbringing as a “little old Indian boy from the rez” who made it to the NHL.

“My hope is that my hockey story helps show kids from home what’s possible,” he wrote. “I always tell them that education is freedom.”

For 23 years, Odjick and Leech worked together to run leadership workshops for Indigenous Youth. He took being a role model for young people seriously, Leech recalled.

“The work we did with mostly our Indigenous Youth was kind of like medicine for us, we enjoyed doing that a lot and got a lot out of it,” Leech said.

He remembered how Odjick connected with Youth during his short visits to many communities.

Over the years, the pair heard from Youth they worked with, learning about their success stories that they attributed to Leech and Odjick’s support.

“It wasn’t just that we would be given the messages, we were also trying to help and encourage and influence as much as possible,” Leech said.

“We would hear back from them over the years, which always gave a good, warm feeling for us that we were doing our job and doing it right.”

Proud of his ancestry and family

Odjick was proud of where he came from, and he kept that connection throughout his life. He always honoured the struggles of his father, a residential “school” survivor.

In fact, his chosen jersey number — 29 — was the registration number his father was assigned when he was forced to attend the residential “school” in “Spanish, Ont.”

Leech recalls discussing Odjick’s jersey with him, and once told Odjick, “You brought good spirit to number 29.”

Through their discussions, Johnston recognized the impact Odjick had on players, including New York Islanders defenceman Ethan Bear — who is Cree from Ochapowace Nation in “Saskatchewan” — who grew up following in the footsteps of Odjick.

“He was so important to young Indigenous people across the country,” Johnston said.

Leech noted that Odjick’s accomplishments and recognition weren’t limited to young people but spanned every generation. Many Indigenous people looked up to him across the continent.

“What made Gino very rich was his reputation in Indigenous country,” he said.

Leech recalled how Odjick loved visiting reserves during their workshops and taking the Youth to events, so they could experience new things — such as attending the Pacific National Exhibition (PNE).

Odjick also met with political leaders to advocate for more resources for First Nations, ensuring that eradicating poverty on reserves was an ongoing objective.

Before he died, he requested a celebration of his life be held at Musqueam Nation, his home for more than three decades.

At the time, Musqueam Chief Wayne Sparrow remembered Odjick as a “longtime friend” who became like “family” — always “grounded in his culture and sharing stories of where he came from and what he overcame.”

Revealing ‘the human Gino outside of the hockey player’

For Johnston, co-writing Odjick’s biography was a change of pace compared to his regular daily newspaper sports reporting.

“I’m really happy with what we were able to pull together,” he said.

Leech began his writing process by dividing Odjick’s story into four separate sections — Odjick’s early life, his hockey career, his life after hockey, and what he was like as a person.

The book flows through Odjick’s life, offering readers a new perspective through previously untold stories.

Leech recalled encouraging Odjick to tell his own stories, but that his friend was hesitant to do so at first — because it meant speaking about his background as a father, his relationships, and his mental health struggles.

But to Leech, that’s what made him a well-rounded person.

“What we were trying to resonate in the book is the human Gino outside of the hockey player,” Leech said.

Leech hopes the book won’t just be for Odjick’s large fanbase, but inspire others for years to come — especially “young kids,” Leech said, who “pick up the book and learn” from the Algonquin athlete’s example.

“Because his story and message never changed over the years,” he said of his late friend. “For young people, it was always about education.

“Education is freedom: you have the freedom to make choices.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

Book remembers ‘fighting spirit’ of Gino Odjick, hockey’s ‘Algonquin Assassin’

Biography of late Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg left winger explores Odjick’s legacy as enforcer in the rink — and Youth role model off the ice

-

St. Augustine’s survivor hopes for closure after evidence of 81 unmarked graves released

50 years after the residential ‘school’ closed, shíshálh Nation announces evidence of many burial sites. A Tla’amin Elder wonders how many more children died