Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw designs colour the streets of ‘Victoria’ with city’s latest banner project

With five new contemporary designs, Lou-ann Neel wanted to show appreciation for tiny beings such as ladybugs, dragonflies and bumblebees

Colourful Kwakwaka’wakw designs featuring plants, hummingbirds and insects are adorning the streets of “Victoria,” as 400 banners with work by artist Lou-ann Neel are installed around the city.

Neel has created five new pieces of art as part of the city’s summer banner program, which has been running since 1970 and commissions new banner designs for the downtown core and James Bay every two years.

Neel descends from the Mamalillikulla, Da’nax’daxw, Ma’amtagila, ‘Namgis and Kwagiulth tribes of the Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwak’wala-speaking people) and is originally from Alert Bay.

Spending so much time in the “Garden City” where she now resides, Neel wanted to show appreciation for the natural plants and animals that make up the local ecosystems.

The designs are also contemporary and whimsical, with smiling faces on the insects happily going about their work.

“People always look at Native art, and it’s very immersed in tradition and comes from traditional stories,” Neel said in an interview with IndigiNews.

“We are a living culture, and we create fun things too.”

The animals featured on the five banners are ladybugs, bumblebees, hummingbirds, dragonflies and a “crystal garden” design which brings various creatures together.

In a statement for each design, Neel shows appreciation and gratitude for each of these beings.

“I wanted to acknowledge dragonflies for the great work they do feeding on mosquitoes and gnats — something gardeners appreciate a great deal,” she says in the artist statement for her dragonfly banner.

“Their beautiful array of colour complements any floral environment. In many Indigenous cultures, the dragonfly is often recognized as a symbol of positive change, as it contributes to positive growth and change each and every day.”

Now that the banners are complete, Neel said she is looking forward to focusing more on carving as a medium, something that’s entrenched in the history of her family’s artistic process.

Carving holds a special place for Neel as she wishes to challenge the narrative that carving was something only men did. In her travels along the coast, Neel has confirmed that women carved in many communities along the coast.

“Amongst our people, we know that women carved,” she said.

Neel believes that carving is important to her not just because of family tradition, but also to serve as a positive role model for upcoming generations and to challenge patriarchal narratives.

“I don’t want young people to have that kind of messaging,” she said. “I want them to have encouraging messaging.”

Living culture, not artifacts

Along with encouraging the next generation of artists, Neel is passionate about advancing the narrative for Indigenous art, and bringing art traditions into the present moment.

As a repatriation specialist at the Royal BC Museum, she said it’s important to trouble the term “artifacts” — which implies that the items are central to the past rather than being utilized in ceremony and culture to this day.

“I got really concerned about that, because it was part of erasure. We have already been so erased in terms of our roles as artists,” she said.

Neel said many museums and other colonial institutions are hesitant to repatriate items for various reasons, mostly because they represent valuable assets and a financial bottom line.

“We’re talking about truth and reconciliation. To me repatriation [is] reconciliation in motion”

Pressure in recent times has led to many beginning the complicated repatriation process, including the Vatican after Pope Francis recently spoke about the importance of returning stolen “artifacts.”

“I think that they’re starting to see that there’s a larger moral issue, but also a legal one,” Neel said. “If you don’t have the receipt, you shouldn’t be holding it”

Neel said there’s still a lot of exploitation of Indigenous artists, which is why she has been a vocal advocate for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP).

“I don’t know what it would take to get the political will to make the changes that are necessary. There is no shortage of really sharp people that could make this happen if the politicians would just line up behind it,” she said.

One example of what she is hoping to see would be the creation of Indigenous maker spaces in Indigenous communities that would serve as a space for artists to collaborate and create — not necessarily just for commercial artists, but for those who just want to create and continue traditions.

“The last time we came close to having the luxury of that kind of support and that kind of space was … between the ‘70s and ‘80s,” Neel said.

“When we used to have the Indian Arts and Crafts societies, every province in Canada had one and then the funding got yanked out from everyone in the mid ‘80s.”

As Neel nears 60, her encouraging message to young Indigenous artists is to keep learning, as she is still personally excited about all the things she has yet to learn.

“The more I learn, the more I can express, and the more I can manifest my art. There is nothing more exciting than that.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

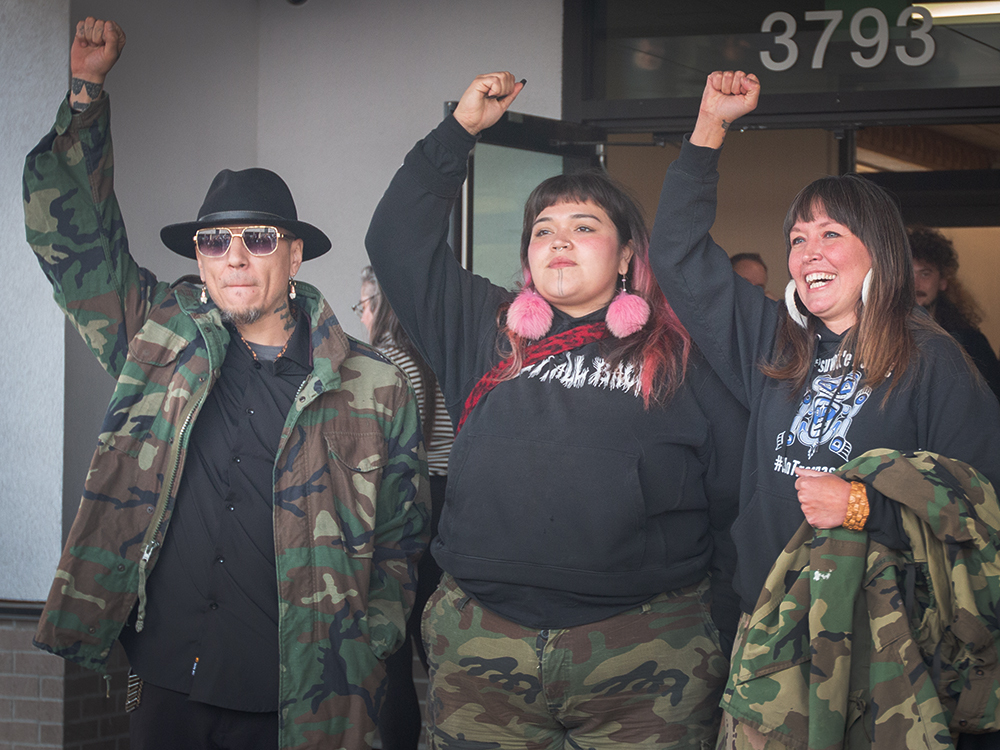

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

-

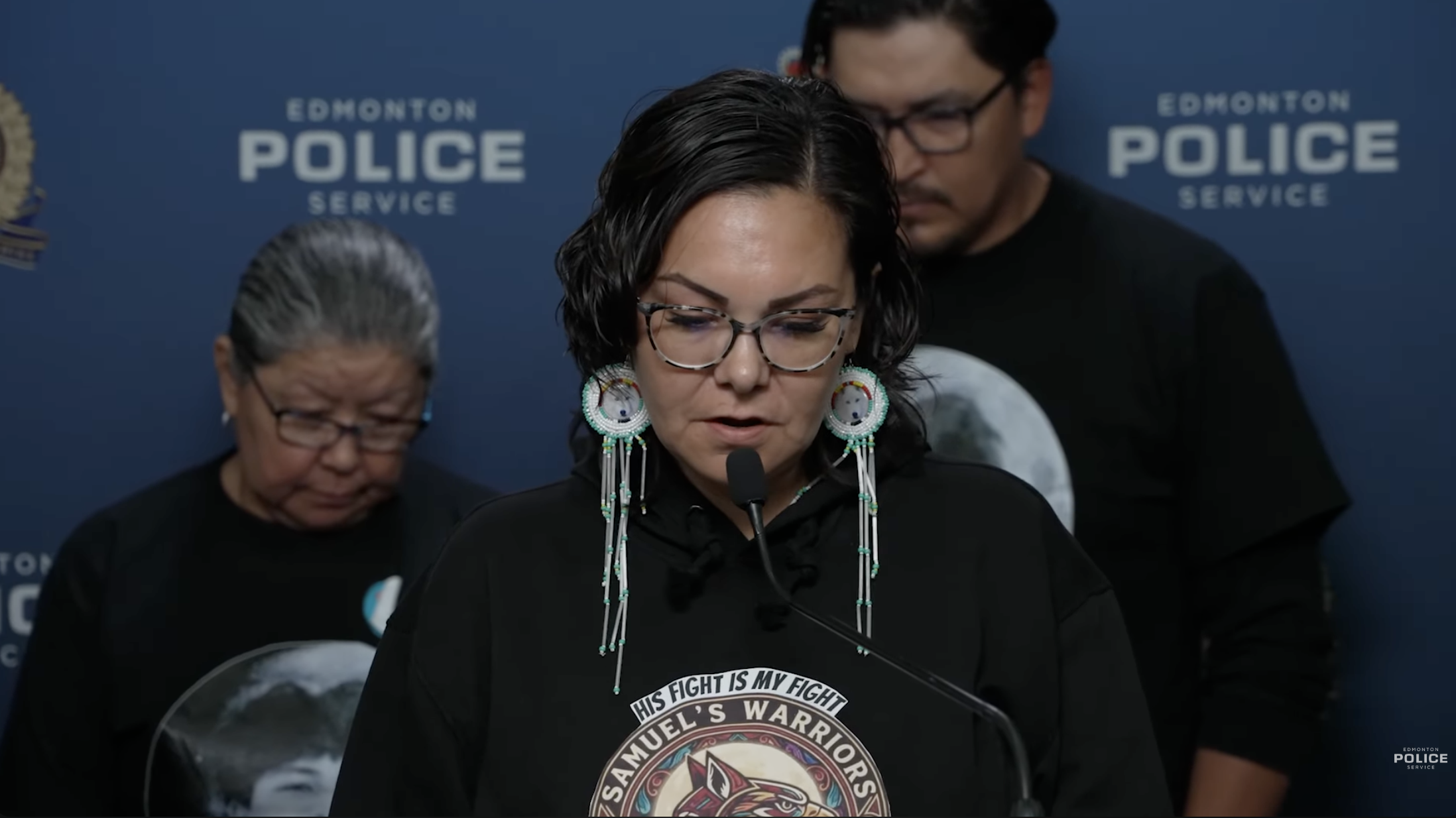

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death