Nisga’a writer Jordan Abel challenges terra nullius in his latest book, ‘Empty Spaces’

A conversation about what it means to be Indigenous without access to ancestral homelands

Jordan Abel is taking the land back one word at a time.

In his newest work, the award-winning poet and writer offers a meditation on what it means to be Indigenous when you are far from your homelands.

Empty Spaces is a poetic, genre-defying reimagining of James Fenimore Cooper’s 1826 novel The Last of the Mohicans and modern Indigenous culture. With Cooper’s descriptions of the land as a starting point, Abel rewrites and reframes the landscape from his perspective as a contemporary urban Nisga’a person living far removed from his ancestral territories.

As Abel’s first work of fiction — his previous works have been autobiographical — its exact nature is hard to define. A work of utter originality and beauty, the audiobook is narrated by Blackfoot and Sámi filmmaker and actor Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers and the gorgeous book cover was designed by Cree and Métis visual artist, Michelle Sound.

IndigiNews spoke by telephone with Abel, author of three poetry collections and the award-winning memoir NISHGA, about his new work.

IndigiNews: Please tell us about Empty Spaces. What was your inspiration?

JA: The short version is this is a book I started writing about seven years ago. I was reading a book called An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by a writer named Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. In it, she makes the argument that the work The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper was instrumental in nullifying the guilt related to genocide, a really powerful argument to make about a piece of literature and the way it shaped American nationalism.

That got me interested in The Last of the Mohicans. That book is all kinds of things — most of which I don’t like — and I was curious about how people received that work. On Goodreads, there were so many reviews from American high school students saying it was really boring because of the endless descriptions of nature. I started thinking about those descriptions and how I could shape and potentially rewrite them.

Seven years is a long time. Why was it important to you to reimagine Cooper’s book?

My impulse is always to respond to and write back to historical inequities. The catalyst for this book was how Cooper imagined a kind of terra nullius on Indigenous lands — the idea the land was empty, uninhabited, just a blank canvas. That was what I wanted to respond to. Over seven years, the book moved beyond those initial catalysts, but that origin point was to respond to and critique that work.

You’ve taken an experimental and creative approach in Empty Spaces. What do you hope readers take from the book?

As an urban Indigenous person, a Nisga’a person displaced from my traditional territory, I personally don’t have access to Nisga’a territory right now and haven’t for almost the entirety of my life.

That was the subject of my previous book, NISHGA. In that book, I write about my grandparents’ experiences in the Coqualeetza Residential School and how that violence inflicted upon them seeped into my dad’s generation and my generation, as well. My family was slowly displaced from Gingolx, where they’re originally from. I grew up in Ontario, and we’re now kind of scattered all over the Lower Mainland.

I often feel the absence of my relationship with our traditional lands.

One of the things I want readers to think about is our relationship to these lands, both our relationships to Indigenous territory and our relationships to the lands we exist on now.

The majority of Indigenous people in Canada today are urban people living away from their traditional lands. How does the urban Indigenous experience shape this work?

So much of the work that’s happening in Indigenous Studies and in Indigenous literature is very concentrated on Indigenous knowledge and ways of being that stem from our cultures and our traditional territories. Not enough is happening to address urban Indigenous peoples.

As an urban Indigenous person, I really feel that’s an area we need to think about and create spaces for because the majority of Indigenous people are in urban areas and have complicated relationships with our home territories.

My hope, in part, is that this book will tap into that and ask us to reconsider our relationships with urban spaces, as well as traditional spaces.

There’s an Indigenous renaissance taking place within Canadian literature right now. It’s creating opportunities but maybe also putting pressure on Indigenous writers in terms of how they represent their people. What has your experience been?

It is an incredible moment that we’re in. There are so many amazing Indigenous writers that it is impossible to keep up with all of the amazing writing that’s coming out in Canada. We’re incredibly lucky as readers to experience that.

I do feel as though the publishing industry and maybe the reading public have very particular shapes in which they want to see Indigenous stories appear, and sometimes it feels like you have to write in a very particular way in order to sell a book. That’s an idea I want to push back against. I want to write in my own way, whatever way that is.

“Empty Spaces” was released on August 29 from McClelland & Stewart and is now available at bookstores everywhere and as an audiobook.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

-

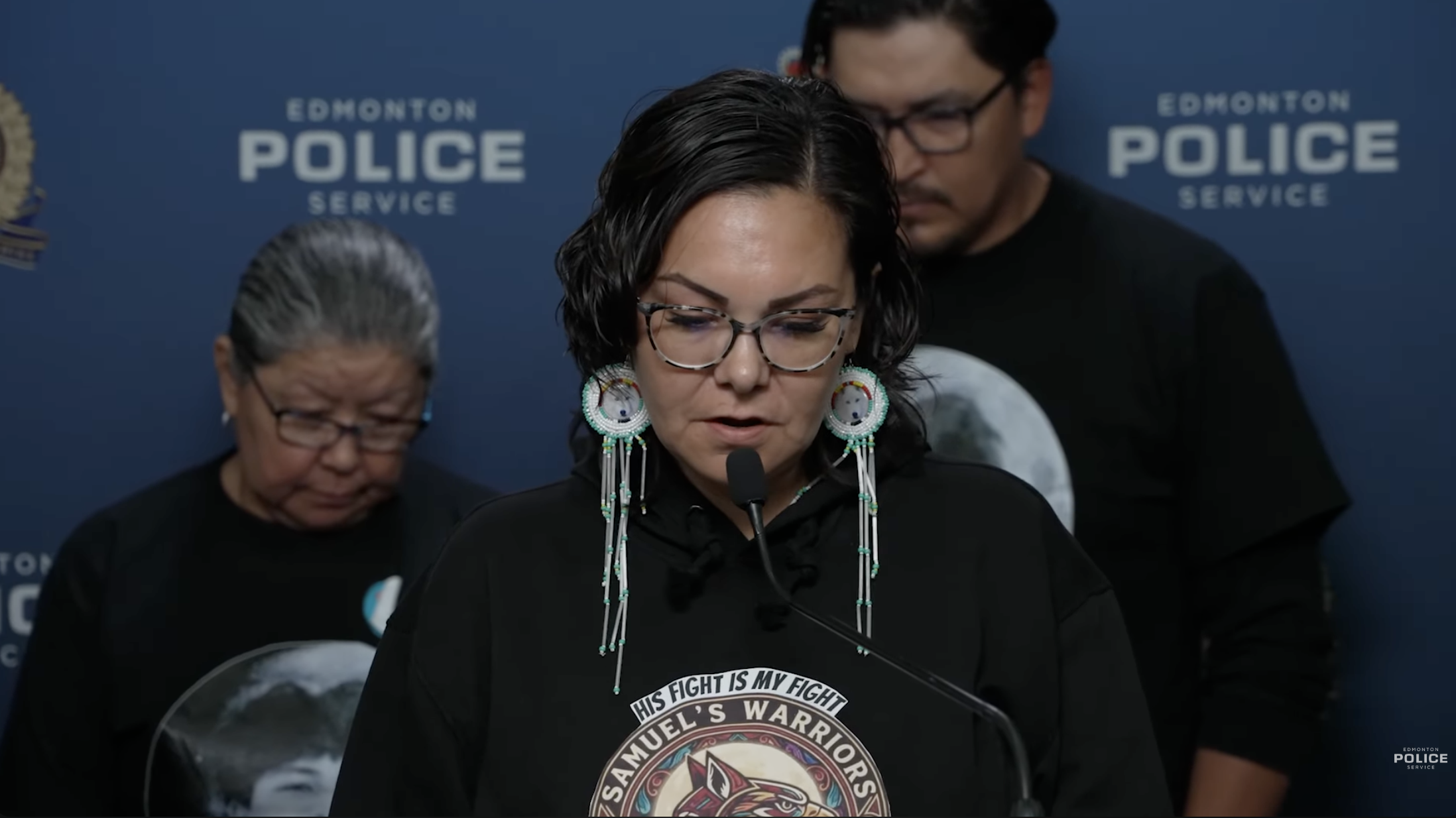

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death