Family and friends gather strength through ceremony to continue their search for Bear Henry

A group gathered for a vigil in Beacon Hill Park on a cold morning in early January

Content Warning: This article contains content about missing Indigenous kin, including the mention of Willy Pickton and residential “schools,” which may be triggering. Please read with care.

On a cold Saturday morning in early January, friends and family gathered on lək̓ʷəŋən and W̱SÁNEĆ territories, in downtown Victoria’s Beacon Hill Park, to hold vigil for Bear Henry, last heard from in late November, 2021.

Bear is a Two-Spirit person from Spune’luxutth (Penelakut). Friends and family say it’s unlike them to be out of touch. Bear loves to post on social media and is strongly connected with their community.

Before the vigil began, the air was somber and quiet. Those arriving moved slowly, awkwardly, as if they wondered if they belonged. Some couples stayed together and watched from a distance.

But the mood shifted when members of Bear’s family called the group in. Aunty Rose Henry led with her strong voice. She invited those gathered to share words of what they knew of Bear, to uplift Bear’s mother and uncle, Eileen and James, who stood at the centre of the circle.

One by one people from the crowd stepped forward to say a few words, some confident, others trembling in their tributes.

Standing there, the three of Bear’s kin gave the sense of people who know how to support each other through shared grief.

“I’m pretty amazed at the amount of people that have shown up because they all know they’re from different parts of [Bear’s] journey,” said Aunty Rose, in an interview at the vigil.

Through Aunty Rose’s leadership, through ceremony and songs and drumming and story, the group that had been disconnected became one. Four hours later, many still stood, shivering, lingering in the precious moments of connection.

A helper

Beacon Hill Park is a significant location to Bear. A year ago, Bear was one of the unofficial, volunteer outreach workers at the Meegan Community Tent, which supported the people living in the park through the cold winter.

The Capital Daily profiled Bear last year, highlighting their work supporting people in need and reconnecting a family blown apart by colonial violence. In that article, Bear describes themself as the “queer mom” of the outreach operation, shrugging at the question of why they continue to show up, day after day.

Bear was “the person that would bring a little bit of sunlight,” wherever they went, Aunty Rose said. They always went above and beyond to help out people sleeping outdoors, making sure they had blankets and someone to talk to.

Some spoke at the vigil of their gratitude towards Bear, who taught them how to embrace their more feminine side. Others called them the kindest person they have ever met, and expressed how much they miss them.

Missing

Bear’s last contact with loved ones was on Nov. 27, when they sent their family a text message from the Lake Cowichan area. Later that day, their van was photographed on Gordon River Main Forest Service Road, near the Honeymoon Bay Ecological Reserve.

Family and friends say they understood that Bear intended to head to the Fairy Creek old growth logging blockades, to ensure Indigenous representation there and to reconnect with their ancestral lands. Bear’s van was camperized and Bear had supplies to be self-sufficient for weeks, Aunty Rose said.

Bear and Bear’s community face inequity in receiving adequate support for the search efforts, Aunty Rose said. As an Indigenous person, as a Two-Spirit person, and as a person from intergenerational poverty, Bear’s “at the back of the pile” for official search efforts.

“Deliberate race, identity and gender-based genocide.” That’s how the chief commissioner of Canada’s inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, Two-Spirit and gender-diverse people described the national crisis.

The 2019 final report found that Indigenous women and girls are 12 times more likely to go missing or be murdered compared with non-Indigenous women and girls in Canada. The inquiry delivered 231 Calls for Justice, imperative action items directed at every government, institution and individual in Canada.

Related article: Beyond Red Dress Day: Seven calls to action for allies

The federal government took two years after that report to release its action plan, which fell short of establishing expected costs, key outcomes and completion dates, APTN News reported. Around that time, the Native Women’s Association of Canada pulled out of the national action plan process, calling it “dysfunctional,” and released its own plan instead.

Bear’s story mirrors the stories of so many missing Indigenous women and gender diverse people. A family ripped apart by residential “schools,” by the Sixties Scoop, by the so-called child welfare system, by racist colonial policies designed to strip Indigenous peoples of their culture, their language, their livelihoods.

Bear is the third member of the Henry family to go missing, Aunty Rose said. Janet Henry disappeared from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside in 1997, and family members presume she was one of serial killer Robert “Willy” Pickton’s many victims. Ian Henry has been missing from the Cowichan area since 2015.

Searching

Getting help from RCMP in the search effort is a major challenge, Aunty Rose said. “There’s not a good relationship between law enforcement and Indigenous people.”

In addition to general distrust, the relationship is complicated by the fact that the file has been transferred from Victoria police to Lake Cowichan, Aunty Rose said. “The Lake Cowichan RCMP are the people that were instrumental in the increasing levels of violence imposed on the Indigenous land defenders at Fairy Creek.”

In an interview with The Discourse, RCMP media relations officer Sgt. Chris Manseau said the police are exploring many different avenues in an attempt to find Bear, including monitoring card purchases, canvassing for video, speaking with witnesses and more. He explained information as well as photos of Bear and their vehicle were distributed to police stations throughout the Island, and those travelling on the road towards Fairy Creek were made aware.

Manseau added that Bear’s affiliation with the Fairy Creek blockades does not affect police efforts to locate them. “The RCMP take missing person cases very seriously, and that person’s background or their affiliation with whatever group does not factor into this whatsoever,” he said.

Manseau said that RCMP are available any time, including to hear concerns over how the case has been handled.

For those who want to help, Aunty Rose asks people to familiarize themself with Bear’s description and the description of Bear’s van, and to keep an eye out, wherever they live.

Bear is described as a Two-Spirit Indigenous person, age 37, six feet, two inches tall, and about 300 pounds in weight, with brown skin, green eyes and short brown hair. They often wear skirts and leggings. Bear’s vehicle is a 1980 Dodge Royal brown and beige camper van, with B.C. licence plate NB2 06H. The van is covered with phrases like “Land Back” in black spray paint.

The community of searchers is organizing on the Bear is Missing Facebook group and fundraising for search and rescue efforts. They ask that interested people read the FAQ document and share only the official missing person poster. They ask that people who spot a van similar to Bear’s check the licence plate before calling police, to avoid disturbing the owners of similar vans.

Comforted by words of truth and wisdom, the sound of drums, the smell of smudge and the taste of tobacco, the group in Beacon Hill Park stood together as one. They held each other up and gathered strength for a renewed search effort. [end]

This story was reported by Philip McLachlan and edited by Jacqueline Ronson, both settlers on Coast Salish territories. Kelsie Kilawna, sqilxw Cultural Editor and Senior Aunty for IndigiNews, strengthened the article with cultural and trauma-informed edits.

For Indigenous kin: A National Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former students and those affected. Access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866 925-4419. Within B.C., the KUU-US Crisis Line Society aims to provide a “non-judgmental approach to listening and problem-solving.” The crisis line is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Call 1-800-588-8717 or go to kuu-uscrisisline.com. KUU-US means “people” in Nuu-chah-nulth.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

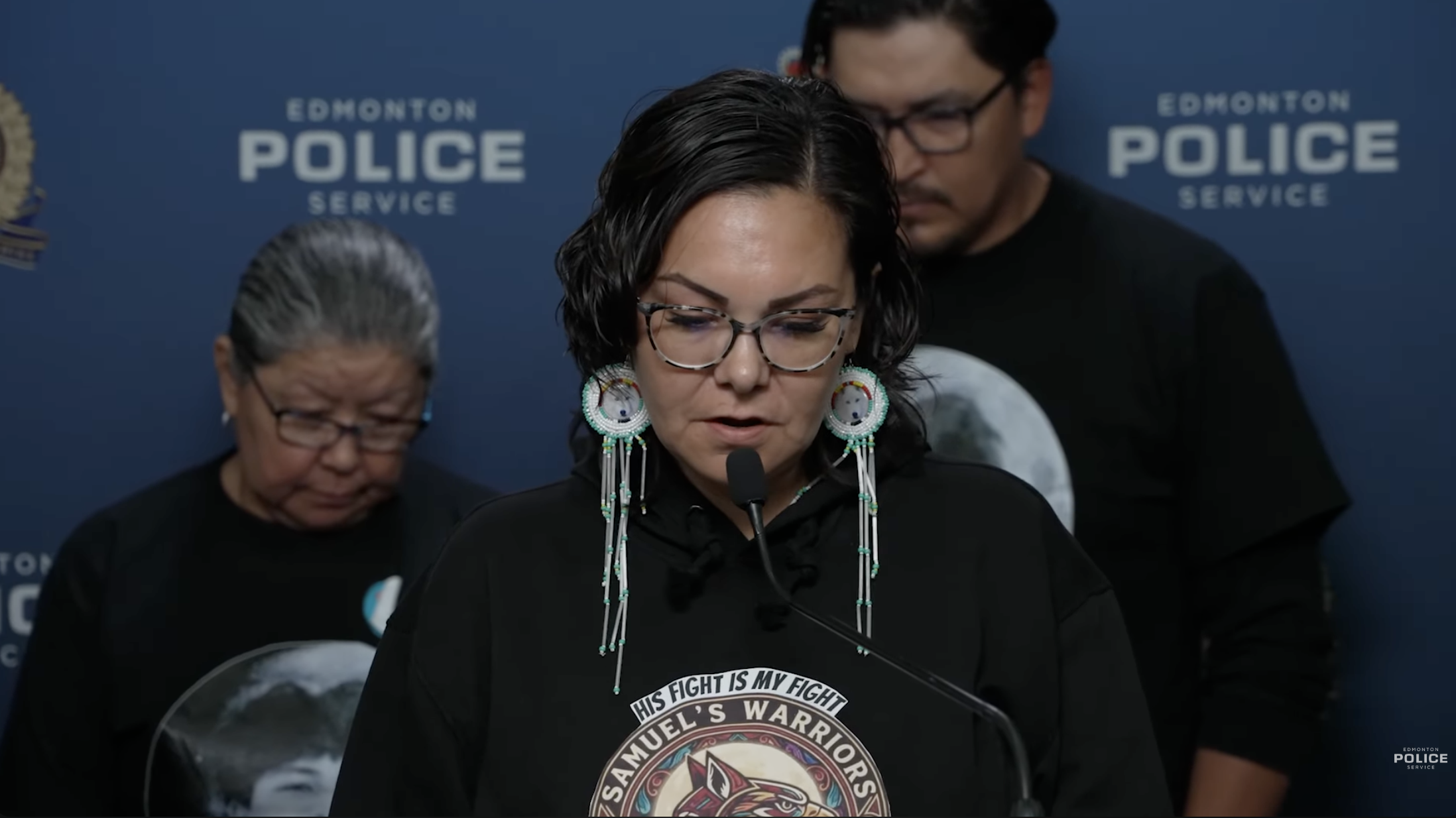

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death

-

Book remembers ‘fighting spirit’ of Gino Odjick, hockey’s ‘Algonquin Assassin’

Biography of late Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg left winger explores Odjick’s legacy as enforcer in the rink — and Youth role model off the ice