In Treaty 9 territories, conservation is at the heart of a birchbark canoe build

Preparing and weaving roots and bark, Chuck Commanda led a workshop teaching the craft during a week-long moose gathering in northern ‘Ontario’

Sitting around a pot of boiling water filled with spiraling spruce roots, a group of people outside the Wahkohtowin Development office in “Chapleau, ON,” are stripping pieces of the softened wood in preparation to build a canoe.

The best roots for the job are found below the tips of the spruce branches, away from the trunk. They’re narrow, flexible and easy to find, says Chuck Commanda, who patiently guides the group in the traditional practice that’s been passed down by his ancestors.

The plan is to build a birchbark canoe, bolstered by the tough and pliable spruce roots, in an Algonquin style that was once commonplace in these Treaty 9 territories of northern “Ontario” but now only practiced by a few builders like Commanda.

The group includes Wahkohtowin Guardians, who will help build the entire canoe, and community members from Chapleau Cree First Nation, Missanabie Cree First Nation, and Brunswick House First Nation.

About a dozen people from northern “Manitoba” are also helping with the build. They traveled to the area on July 15 — with academics and a representative from Nature United — to spend the week talking about moose, whose populations are declining in these Boreal-forested territories. Together, they’re forming a “moose alliance,” and their discussions about conservation continue as they work on the Guardians’ birchbark canoe.

For Chapleau, Missanabie and Brunswick Guardians — a program belonging to social enterprise Wahkohtowin Development — this is their fourth year of crafting the birchbark canoes.

It’s a craft that was passed down to him by his grandparents, skipping his parents because of residential and day “school.”

“I was one of the lucky ones,” he said. “My grandparents kept that craft alive.”

The invitation to learn canoe making was extended to all of the grandchildren, but it was Chuck who ran with it — becoming his grandparents helper and learning everything he could from them.

During the winter months, Commanda, who is Algonquin from Kitigan Zibi in “Quebec,” said his grandfather would encourage him to make small, four-foot model canoes. He says he wasn’t sure why, at first.

“I learned later on that if I made a mistake there was still the material handy right there at my feet,” said Commanda. It was a way of creating spare parts, while perfecting his craft.

As a young man, Commanda drifted away from canoe building. But while recovering from a car accident in 2008, he began making baskets, paying homage to his grandmother, who was often behind the scenes of her husband’s work.

“I wanted to let the world know she was really 50 per cent of the canoe making business,” he said.

Commanda became so good at basket making, he was invited to the National Museum of the American Indian in “Washington, DC” to display the baskets alongside an eight-foot canoe which he made on a whim with extra materials.

“My grandfather got wind of that,” said Commanda. In 2011, his grandfather phoned him up and asked him to visit.

Commanda’s grandfather, William Commanda, was co-founder of A Circle of All Nations, a “global eco peace community” that used the medicine wheel framework to bring together Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples from across the world, to pray collectively for Mother Earth, environmental stewardship, racial harmony and peace building.

Guardian of three Algonquin wampum belts, Officer of the Order of Canada, and with two honourary PhDs, Commanda’s grandfather explained that the 2011 global gathering had the theme “watercraft,” as all races and cultures at some point in their existence used the watercraft, no matter where they came from.

His grandfather asked if he’d make him a canoe for the occasion.

“And the minute we finished it, he came and inspected it, gave me the thumbs-up, and he passed away not too long after,” Commanda said.

“To me that signified that the circle is complete. I was no longer the student. I am now the teacher.”

There’s a number of steps to building a birchbark canoe, he explained.

After the materials are gathered, spruce roots are stripped and prepared and the bark is laid out. A plywood template is made, temporarily installed and weighted. The sides are raised, ribs and stems are installed for strength and speed. Finally, the canoe is held together using the spruce roots and sticky gum.

Many of the Guardians return each year to learn from Commanda, whose twinkly eyes and generous nature inspires some to dream about the craft as a full-time career.

“I just think that would be so neat,” said Amberlee Quakegesic, who makes baskets, jewelry and now canoes. She wants to make her own four foot canoe to practice and collect spare parts, just as Commanda was taught by his grandparents.

Commanda and his team completed the canoe in eight days. IndigiNews wasn’t present for the launching ceremony, but Commanda says it was “a great success.” He’s borrowing the canoe to take on the road for his next build with another First Nations community, north of “Chapleau,” before heading back south to his home in “Ottawa.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

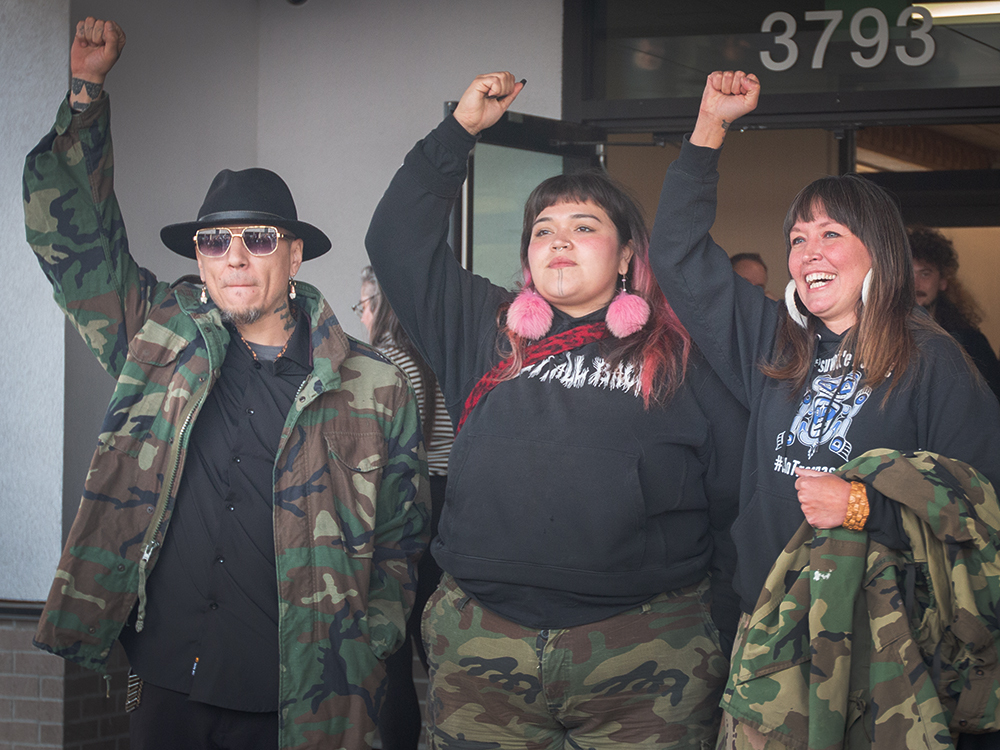

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

-

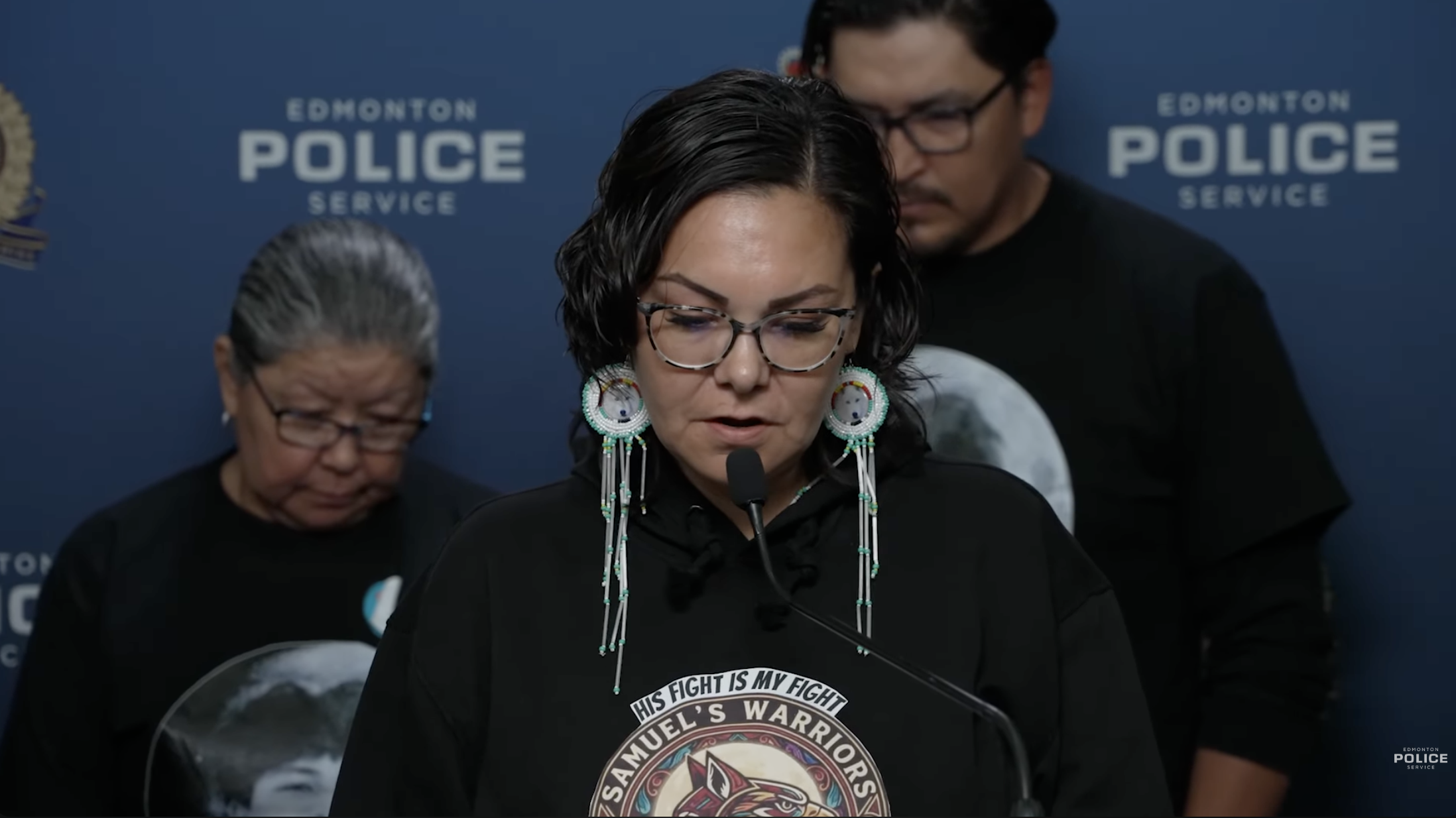

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death