Jeannette Armstrong, trailblazer in literature and language, appointed to Order of Canada

The author and scholar from PIB sat down with her granddaughter to reflect on the award and what motivates her

At the age of 15, Dr. Jeannette Armstrong’s (lax̌lax̌tkʷ) passion and flair for writing was validated when a poem she wrote was published in a local newspaper.

“Very early on, I was publishing when I was still in high school and it was poetry — bad poetry, mind you, it wasn’t very good,” she says humbly.

This particular poem — which was about John F. Kennedy — marked the “first baby steps” of her journey as a writer. Armstrong continued to work on her craft and, years later, went on to become recognized as the first Indigenous woman in “Canada” to publish a novel.

It’s for this achievement and many more — her efforts in preserving the nsyilxcen language, her work supporting other Indigenous writers and her work as an educator — that Armstrong is being appointed to the Order of Canada.

‘All about giving a voice’

Armstrong’s contributions to Indigenous literature have garnered recognition not only within her local community of Penticton Indian Band (PIB) and the Okanagan but also on a global scale.

In 1978, she graduated with a diploma in Fine Arts from Okanagan College. She then obtained a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Victoria (UVic) with a focus on Creative Writing.

She played a vital role in the development of establishing Theytus Books at the En’owkin Centre in 1980, which became the first publishing house in the country owned and operated by Indigenous people.

“The En’owkin Center publishing program is all about giving a voice, not only to our people, but to other Indigenous people,” says Armstrong.

In the mid-1980s, she published her first novel titled Slash. The book tells the story of a young Okanagan man — weaving together the impact of the education system, Christianity, and organizations like AIM (American Indian Movement) during the transformative 1960s and 1970s.

According to Armstrong, her targeted audience was the young people in her communities to read something that was written about syilx people and underlying issues some may have faced in that time period. Slash is now utilized in many high schools, colleges and universities.

“I wanted to make sure Slash covered a period of history from one person’s perspective, it doesn’t represent anybody that I know, but I really wanted to speak from what I knew as a syilx person and as a young person at that time with what was happening,” Armstrong explains.

“I wanted to say things about us as syilx people because I never read anything about us when I was growing up. It was like we didn’t exist.”

Canada’s research chair

In 2002, Armstrong began working as a part time professor at the Okanagan University College (OUC) before the institution became known as the University of British Columbia Okanagan (UBCO).

This work inspired Armstrong to further her education, so she could create more space for Indigenous education, research and Indigenous voices to be heard.

Armstrong obtained her PhD in Indigenous Environmental Ethics and Syilx Indigenous Oral Literature from the University of Greifswald in Germany in 2009.

She is now an associate professor at UBCO and the Canada Research Chair in Okanagan Indigenous Knowledge and Philosophy.

Her primary research and writing focuses on analyzing syilx captikʷl (the documentation of syilx knowledge).

“I’m a very serious activist in terms of protecting the environment and standing with others that are doing the same thing,” she says. “I have always been engaged in activism through my writing.”

Her contributions to literature have earned her accolades and awards, including receiving a Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award in 2016.

In 2021, Dr. Armstrong’s brilliance was further acknowledged as she was elected as a fellow of the esteemed Royal Society of Canada, an exclusive organization of more than 2,000 scholars, artists and scientists.

Recently, she was the academic lead for UBCO’s Bachelor of nsyilxcən Language Fluency (BNLF) program. This pioneering program saw its first syilx graduates this past June.

“We have to help individuals learn the language so they can become teachers and contribute to that,” Armstrong expressed.

However, she says it took a community to achieve this.

“We’re never alone in achieving anything, we always have many others that are putting their hands and their minds and their hearts into things,” she says.

An officer of the Order of Canada

On June 30, Governor General Mary Simon revealed a list of 85 new Order of Canada appointees which included Armstrong.

The Order of Canada is considered one of Canada’s highest civilian honors, as stated by the Governor General of Canada’s website, and aims to acknowledge those who have made exceptional and lasting impacts on the country.

The Order is distinguished into three levels: companions, officers and members. As an officer of the Order of Canada, Armstrong has been recognized for her contributions to Indigenous literature, as well as her work to preserve Indigenous knowledge and the nsyilxcen language.

Dr. Armstrong received her pin in the mail but will also be traveling to “Ottawa” for a ceremony to receive her official recognition by the governor general.

Reporter Athena Bonneau — Armstrong’s granddaughter — sat down with her to ask about her most notable contribution to Indigenous literature, some of her favorite work, and her inspirations. This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

Athena: Could you tell me about some of your major contributions to the community leading up to you being honoured with the Order of Canada?

Jeannette: I’m one of Canada’s writers who is recognized for literature, because I felt that the way that our stories, our understanding of the world and ourselves, are portrayed through literature, is important. So that was one area. But the main area, I think, was really in the support for our nsyilxcen speakers to revitalize and work in, not only protecting the language, but also making sure we could give language back to those who were not fortunate enough to learn it because of residential schooling and public schooling and all the ways in which it is not understood very well.

It’s not just residential schools. Public schools take away our language every day. For every child that goes there, they don’t get the language. They don’t have the language programming there. They don’t have money for it. So all of those things, to me, were important. If it’s not gonna be there, then somehow we have to try to help the communities to provide that.

So it’s the language and the literature that I’m being recognized for.

A: What inspires you to be a writer?

J: The main reason you’re writing is you’re trying to put into words something that’s important — say, as a syilx person or as an Indigenous person, and as an activist. But you never feel that it’s done. You never feel that it’s good enough. You always feel like, ‘I gotta do the next one.’

Writing takes a lot of time, and I’ve had to put it on hold. Same with my visual art. I’m a painter and visual artist. I have an undergraduate degree and I really love doing art but it takes all of your focus, and all of your time. So I had to put that on hold and mainly work for the people.

I’m doing a lot more academic writing now, which is not the same thing as literary writing, which I really love. I love writing poetry, and I love writing stories.

A: Have any authors or specific pieces of literature inspired you to become a writer?

J: Yeah, of course. I really admire other writers like some American writers, Indigenous writers. I was reading Navarre Scott Momaday — House Made of Dawn and The Way to Rainy Mountain. I was also reading Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony and other novels that were groundbreaking. Also, a lot of poetry that was being written and being published, just sporadically here and there in Akwesasne Notes and Indian World and other magazines like that. Peter Blue Cloud and his writing, for instance, and others who were in Canada writing poetry and beginning to write novels.

When Beatrice Culleton Mosionier came out with In Search of April Raintree, that was, for me, a really important novel. And Ruby Slipperjack’s Honour the Sun. That novel for me was speaking about two things that really matter in our lives: our land and our community, and then the violence that’s going on, which one needs to not only live with, but find a way to work around in our communities. And so that novel was really, for me, it was also an important novel.

A: How would you describe the theme of some of your literature?

J: To tell the truth. That whole idea of truth and reconciliation. For me, truth-telling is part of what writing is about, whether it’s poetry or short stories or fiction. In fact, you can tell more truth in fiction and in poetry than you can by writing history and nonfiction. Because you have to stick to what you know. Otherwise, but you can fill in all the gaps and you can dramatize and you can really put a spotlight on what you want as a writer.

A: Can you take me back to the time when you first felt the need to advocate for Indigenous people, language, culture and rights?

J: At a very young age I was engaged with activism. I guess I was always environmentally-aware because of my parents and my grandparents. My grandmother was always very much opposed to developments that would destroy the land for the tmixʷ — that’s the living relatives out on the land. She was a very strong activist who tried to protect what our community lands are in the reserve from development.

Also, my dad, for instance. He was one that said: ‘our land is important and our tmix, who live with us, and we want them to live with us, we love them.’ So the only way people are going to really understand that is if they understand the language and understand our way of being together with all the other living things and not destroying them

A: What kind of work have you done as an environmental activist and as an Indigenous activist?

J: I have international recognition as an environmental activist. I get called to international conferences to give talks and papers and to speak. So, there’s a lot of work that I’ve done there and I think going to be really valuable in terms of how and how we as Indigenous people need to stand up for the things that we believe in. Also, the increasingly-important environmental work that needs to be done to fix what’s going on in the environment, this climate change and climate crisis and all that.

So that’s one part. Another part is, our rights as Indigenous Peoples worldwide. I used to do a lot of work, traveling a lot to different countries in South America and Australia and New Zealand, and actively being involved in speaking about the need to recognize Indigenous rights and title. What that means to me is being able to protect the environment, being able to protect our identity, being able to utilize our knowledge and languages in the right way and protect our people from the biases and the racism that is being shown.

A: What has been the most challenging through your whole journey?

J: That’s pretty easy to answer. The residential school had really caused a hatred of our syilx knowledge among some people. It’s still present. That’s still the most challenging thing because you are wanting to offer as much as you can.

What the residential school did to our people was to make them ashamed of our culture and our language, and make them hate our culture and our language, and make them feel like they’re always doing something wrong. If they do anything in our cultural ways, and it hurts our people, it creates division inside each person.

A: What has been the most rewarding?

J: Well, just people enjoying our language and our life and our work.

A: Is there anything else you want to say about your literature, and how it relates to you being honored for your Indigenous literature for the Order of Canada?

J: I’ve decided to put aside my joy of writing. And so I haven’t written anything literary seriously for maybe the last 10 years. it’s a sacrifice, it really is, because that’s all I would rather be doing. I will be able to do more of that as I wind down my work at the university, now that we’ve implemented so many of the things that I was striving to implement there.

My husband, Marlowe and I, worked really, really hard to develop the Indigenous studies program and deliver the best that we can to bring up other young scholars to take over. And that’s what’s happening now. They’re stepping into our gap that we will leave for them so we can do what we wanna do.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

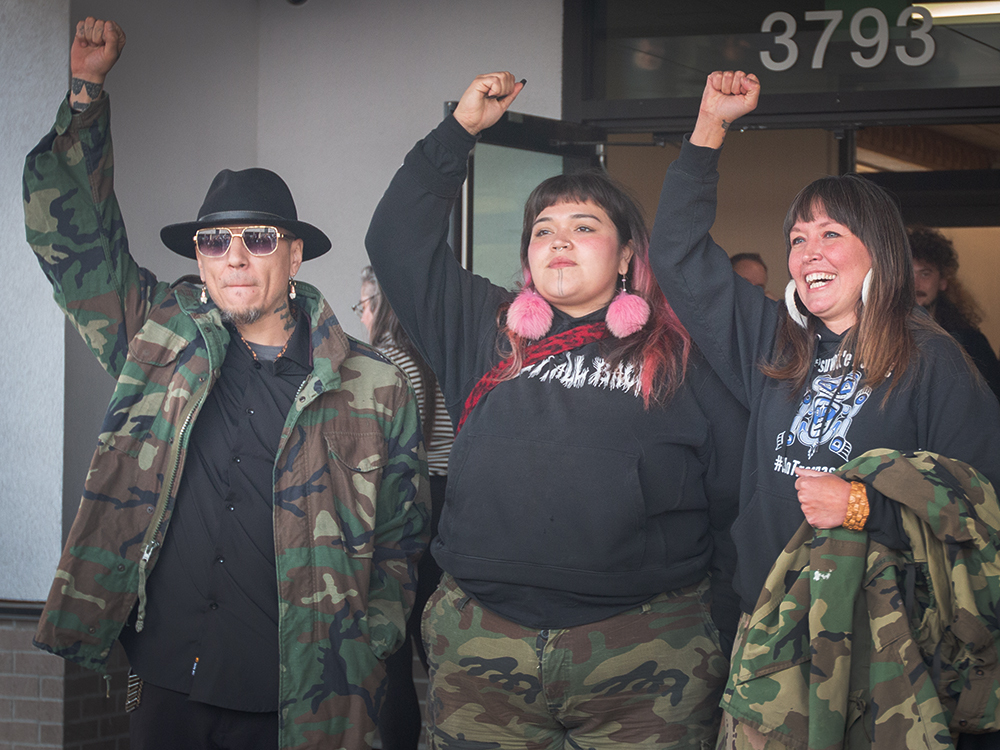

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

-

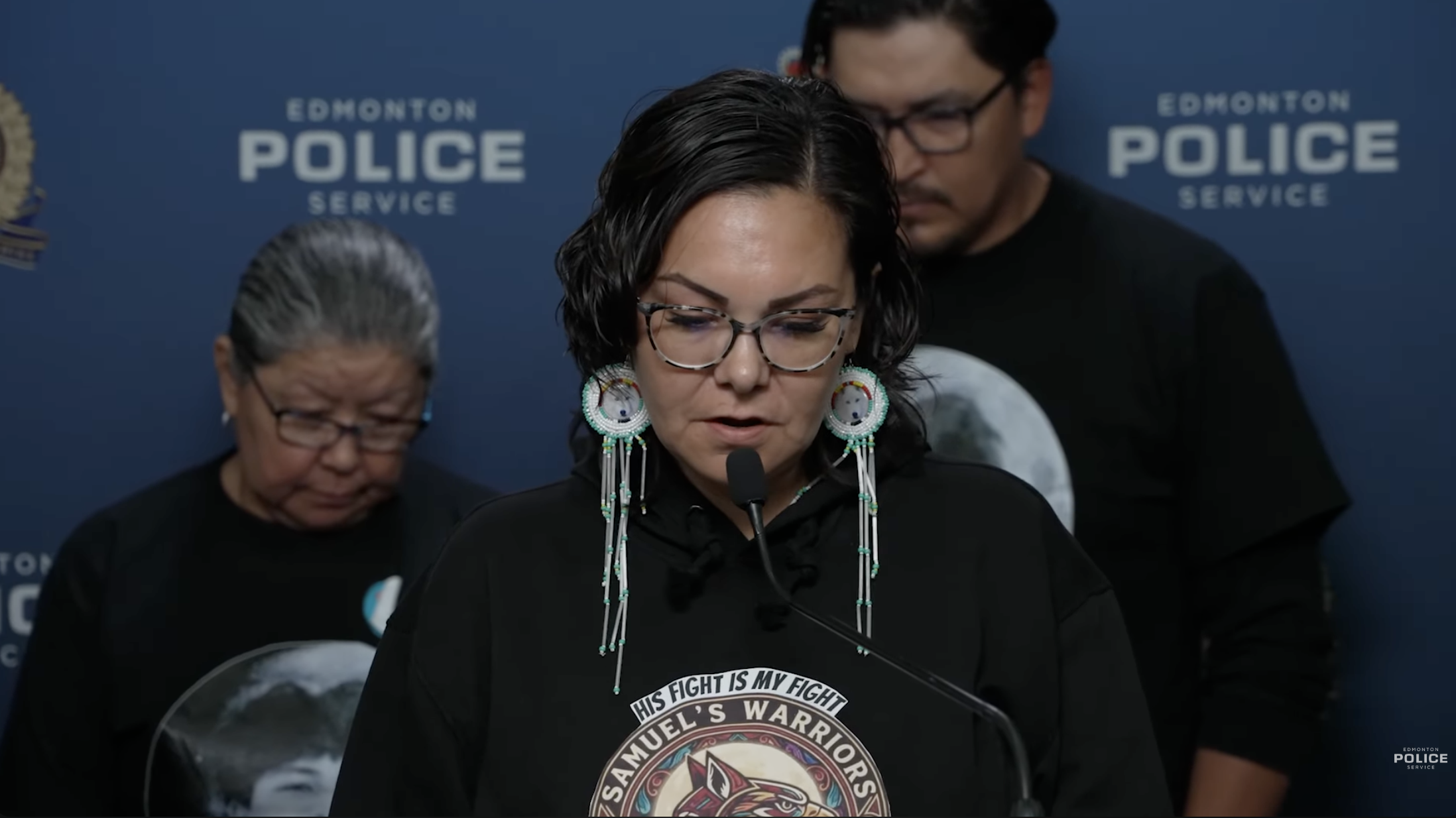

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death