With the foresight of their ancestors, ‘Nuxalk Strong’ highlights a cultural revival

New MOA exhibition goes beyond the notion of ‘colonial trophy cases’ with preservation — and reclamation — at its heart

After blessing the space around him with fluffy eagle down, Nuximlayc Noel Pootlass stands in the centre of the Museum of Anthropology’s main hall.

Surrounded by hundreds of people — and many ancient carvings from around the coast — the Nuxalk Nation high chief invites his relatives to join him in the circle.

“I’d like to call my Pootlass family up to the front,” he says.

As about two dozen people begin to shuffle forward, there’s laughter as he adds: “Actually, it’s the whole crowd.”

Pootlass, along with other leaders and families from Nuxalk, were in xʷməθkʷəy̓əm homelands Feb. 20 to herald the opening of Nuxalk Strong: Dancing Down the Eyelashes of the Sun — a new exhibition at MOA.

The display features 71 Nuxalk belongings from past and present. With some on loan from other museums, or borrowed from the nation in Bella Coola, the exhibition is a visual testament to the community’s lasting culture, powerful resilience and bright future.

‘Thinking and planning for those not yet born’

During a media tour a day before the exhibition opened, co-curators Snxakila Clyde Tallio and Jennifer Kramer stood in front of its doorway — adorned with a Thunder Being design by young Nuxalk artist Anuximana Jade Hanuse.

Entering the exhibition, masks, weavings and rattles are on display amid educational signs and a video showcasing aerial images of Nuxalk territories. A section dedicated to Nuxalk Radio allows guests to engage with the language.

Snxakila said he wanted to share the complexity of the relationships between Indigenous people and museum collections, which are often viewed as “colonial trophy cases.”

Snxakila, who is also the director of culture and language for Nuxalk Nation, has spent 15 years working to discover and collect information about community belongings such as totem poles, canoes, masks, regalia and even human remains from museums.

“As we’ve been doing our research and our work, we’ve come to learn that many of our Elders — the owners of these treasures — made that decision to put these treasures into the museums where they’d be safe and preserved for future generations,” he explained.

“Not an easy choice to make, of course.”

Snxakila spoke of how this preservation became necessary as the Nuxalk Nation’s population was decimated during colonization and the smallpox epidemic — and Indigenous communities were subject to violent policies such as the Potlatch Ban and residential “school” system.

Once home to roughly 20,000 residents, by 1921 there were only about 300 Nuxalk survivors, as the government sold off their land to settlers. Now, the population has risen to nearly 2,000.

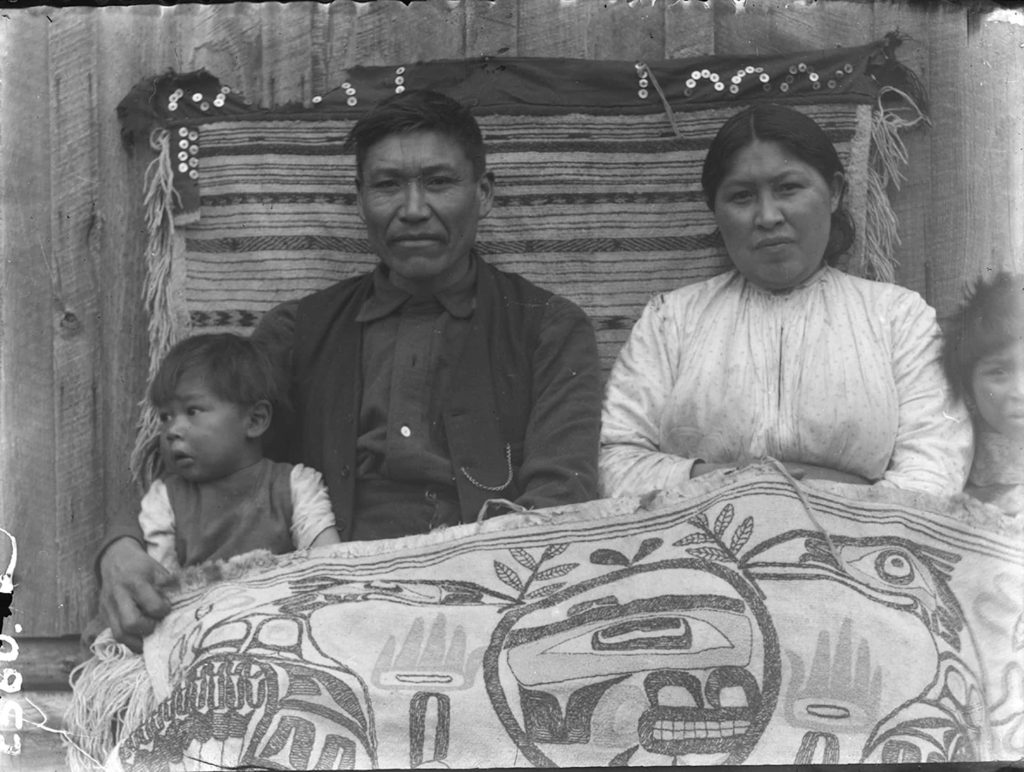

Between 1922 and 1924, a group of Nuxalk hereditary leaders and matriarchs worked with an anthropologist, Thomas Forsyth McIlwraith, who wrote down their smayusta (ancestral origin stories) and recorded more than 120 songs on wax cylinders.

Some masks and other regalia now on display in Nuxalk Strong were given to McIlwraith, and will be returned to Nuxalk by the anthropologist’s grandchildren after the exhibition closes next January, according to MOA.

The Nuxalk leaders’ actions to keep the items safe is one example of putl’altnick, or “thinking and planning for those not yet born,” Snxakila explained — helping to preserve the culture for future generations.

The name Nuxalk Strong itself connects back to a movement in the 1990s when members of the nation — including hereditary leaders — fought against clearcut logging in their territories. Their victorious fight led to the creation of the Great Bear Rainforest.

“This is part of our Nuxalk philosophy, to always be thinking of those to come,” said Snxakila.

“So Nuxalk Strong reflects back to those actions of those Elders, of those leaders.”

Snxakila holds the role of an Alkw, a ceremonial Potlatch speaker in Nuxalk territory.

“Part of my goal was, as an Alkw, to connect the community back to all of those treasures,” he said.

“They’re not just pieces of art, you know. They are our history coming to life.”

While he was doing his research, Snxakila would gather photographs and information about Nuxalk belongings in museums, bringing that information back to his community.

After working with hereditary chiefs and Elders to understand the history and significance behind each piece, his community was able to share in what he learned.

Weaving together past and present

The treasures on display in the exhibit tell their own stories connected to their Nuxalk traditions, Snxakila explained.

“We use the four aspects of Anuqw’ntniknm, which is inspirational creativity,” he said. “So we use storytelling, art, music and dance to make the smayusta … the history of our lineage come alive.”

One display in the Nuxalk Strong exhibition is two pieces of regalia — a potlatch hat and a speaker’s staff — belonging to Helen Housty of Heiltsuk Nation, who married Staltmc Samson Schooner of Nuxalk Nation.

The exhibition has enabled families to reconnect and build unity while learning about their ancestral artwork, said Snxakila.

Community members have since potlatched and “earned the right to wear such ceremonial items again,” Snxakila noted.

“When you go through our exhibit, you’ll be able to see all of these treasures and hear about their stories on how they’ve revitalized the art. So it’s really interweaving the past with the present.”

He said the exhibition is opening doors and opportunities for his nation’s members.

“It’s clearing the path,” he said. “So that’s why this is a big deal.”

Snxakila said at one point, there were no cedar weavers left in the community. Today, there are more than 50, allowing their community to also revitalize wool weaving.

He said the headband he wore to the tour was the first wool-woven item made by the Nuxalk weavers group.

“They had gifted it to me to thank me for my role in revitalizing the weaving,” he said as he stood in front of a wool blanket on display. He spoke of Nuxalk’s “very unique” weaving style.

“And so imagine now as we connect these weavers to the treasures by having them here and our weavers being able to visit them and study them — it’ll help them recreate our style of wool weaving.”

Nuxalk masks are also a prominent feature in the exhibition — representing various supernatural beings and the teachings they hold.

One mask showcases the sniniq’, also known as Sasquatch, who Snxakila grew up learning “can hear disobedient children” and likes to put them in his basket and take them to the mountains.

“Through this dance and this story, we’re able to teach the children about behaving and listening to their parents,” he explained.

“You have to remember our ancestors lived in communal Big Houses, so a child crying around being disobedient at night also affects everyone else in the house. So you can see how many of these beings connect to our real life experiences.”

Snxakila said, during his research, he has found more masks than there are Nuxalk members alive today. Finding so many, he recalled, was an “amazing” feat since each mask would have represented around 10 family members.

Feeling the presence of ancestors

At the opening event, Nuximlayc Pootlass said his grandfather has hundreds of items in museums — estimating more than 30,000 Nuxalk items are in collections worldwide.

To celebrate Nuxalk Strong, dozens of Nuxalk people attended to visit the items and to share prayer, dance and protocol.

Songs announced Nuxalk’s arrival, honoured kinship, and blessed the space.

“It’s an amazing feeling today, and it’s awesome to see all the young people, the Nuxalk, the singers, the dancers that are so gifted,” Pootlass said.

“I’m grateful for all of you coming here to witness.”

Samuel Schooner, elected chief of Nuxalk Nation, said he felt emotional watching Nuximlayc Pootlass dance as he pictured many generations of ancestors before them.

“You can honestly feel them,” he said.

The work is not done for Snxakila, who has been managing the development of the first Big House in Nuxalk in more than 100 years.

Next, he said, he hopes the nation can build its own museum to bring the community’s treasures home.

“We can then study them,” he said.

“We can really connect with our carpenters, our artists, our weavers, to be able to see them with their own eyes and then recreate them, and then bring those recreations out in ceremony in our future Big House — you know, that would be the completion of this work.”

Co-curator Kramer said Nuxalk Strong is a chance to examine museums’ role in removing sacred Indigenous belongings.

“This exhibition demonstrates how museums can participate in nuyayanlh — generous reciprocity,” Kramer said, “by aiding and supporting the Nuxalk as they reclaim their sovereignty through reconnecting to their treasures,” she said in a statement.

For Snxakila, the exhibit holds a special place in bringing people together. The Nuxalkmc can see their history displayed and learn from it. Meanwhile, the general public can experience the thriving culture from Nuxalk’s past to present.

“As a community, witnessing these stories, we’re able to pass on our values, our beliefs, and the things that keep us connected as a community, as well as the responsibilities for stewarding our lands in a good way, and clearing the path for our next generation to succeed,” he said.

“We want to be able to let the world know that we still exist, that we’re still here. We’re thriving and we’re moving forward.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

‘We have a way to save communities’: Cultural fire keepers share knowledge across colonial borders

First Nations experts attend first National Indigenous Fire Gathering in syilx homelands, joining counterparts from ‘Canada,’ ‘Australia’ and ‘U.S.’