Tobacco Plains Youth honoured for creating a ‘home away from home’ for Indigenous students at UBC

Aiyana Twigg’s journey of becoming a leader for Indigenous students at UBC and a champion for revitalizing languages

There was a time in her life when Aiyana Twigg ran away from her culture. A separation from her community combined with a fear of discrimination made the idea of learning her Indigenous language seem so far away.

But after years of growth, hard work and motivation from her family, ancestors and community, Aiyana is leading the way for the next generation of Indigenous Youth in B.C.

In May she was named the recipient of the 2022 Lieutenant Governor’s Medal for Inclusion, Democracy and Reconciliation, for her work within the University of British Columbia (UBC).

The First Nations Language and Anthropology student just finished her studies, but her experience around Indigenous languages started long before she went to university.

If you look back at Aiyana’s childhood, you see that she grew up surrounded by a community that cared about language. Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi ‘it (the Tobacco Plains Band) is part of the Ktunaxa Nation and has, for years, been working to restore their language. Growing up, this embracing of culture was encouraged, but Aiyana’s environment changed drastically when she started attending public school in the “United States”.

The community she grew up in rests on the colonial border of “Canada” and the “United States;” an American town in Montana called “Eureka.” Like most youth in her community, Aiyana attended public school in Eureka.

From Kindergarten through to Grade 12, she learned what it felt like to be alienated, and surrounded by people who didn’t want to understand her, or her culture.

Aiyana felt at the time like she was living two lives: attending school in “Eureka” pretending she wasn’t Indigenous; then coming home and attending ceremonies, all the while keeping it a secret from her classmates.

“After experiencing all that, all I wanted to do was fit in at school. And so I decided that I wanted to stop learning the language, stop learning the culture so that I wouldn’t be alienated.”

This was hard on her family, and community, who were working extremely hard to restore their language and culture.

In 2018, the First Peoples’ Cultural Council (FPCC) reported that there were only 31 fluent speakers of Ktunaxa, the language spoken in Aiyana’s community, and around B.C.’s “Kootenay” region as well as parts of the U.S. In the same report however, they stated there are 343 active learners of Ktunaxa.

The Ktunaxa language is unique in that it is considered a language isolate, meaning there is no apparent connection between it and any other language.

Years later, Aiyana came to recognize the work her community was doing around restoring language, and was inspired by it. So much so, that she pursued it as a career.

“I wanted to be a part of that. I wanted to help support in any way I could,” she said.

The domino effect: Change at home, change on campus

Fast forward to today, Aiyana not only excelled in school but was instrumental in creating safe communities for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students to come together at UBC’s Vancouver and Okanagan campuses. During the pandemic, Aiyana created social media accounts all called @KtunaxaPride, meant to help Ktunaxa youth and diaspora stay in touch.

At UBC, she gravitated towards the First Nations Endangered Languages program, which aligns with her own views as a Ktunaxa and Blackfoot person.

Over her four years attending UBC at both the Okanagan and Vancouver campuses, she accomplished a lot.

She became an advocate for Indigenous students on campus, and welcomed new students on campus. In that position, she hosted a space where these students could come together and face colonialism and racism together, and nurture community.

At UBC Okanagan, Aiyana served as co-facilitator for the Indigenous Living Learning Community (ILLC), and helped facilitate the Indigenous orientation for first-year Indigenous students. This introduced new students to other Indigenous students and built a community which gave them, “a home away from home.”

The space she created with the help of Indigenous Programs and Services served as a place for Indigenous students to seek peer support and have a safe space to practice their cultural traditions.

At UBC Vancouver she became the Arts Indigenous Student Advising peer advisor, working as a peer mentor for students. Simultaneously, she was also the main facilitator for the Indigenous Leadership Collective (ILC), with the goal of building community.

“While I was the facilitator [of the ILC] I focused on creating a space in which we could have fun, laugh, and also enhance our leadership skills. We would do fun activities like painting, game night, while also exercising our traditional practices, in which I lead a smudge workshop for students on campus. We also would discuss matters on campus that we felt needed to be addressed, and were very open about how we Indigenous students can make change in such a colonial space,” Aiyana shared with IndigiNews.

“I think the main takeaway from that position [with the Leadership Collective] was […] I feel like as Indigenous people — or just all marginalized groups of people — we’re always having to be resilient, we always have to have this resilient face and this aura. We have to be strong, but it gets really tiring,” said Aiyana.

“I was just trying to show them that it’s okay to feel weak, to feel fragile, to feel like you’re not at your best. And that, that was a space for them to feel that way.”

Just like creating safe spaces for youth outside their communities, Aiayna believes in putting the power back into the hands of Indigenous people.

Outside of her school community, Aiyana is already making waves.

In the last year she worked as an undergraduate research assistant on a project revolving around relational lexicography, called RelLex, which essentially aims to provide toolkits for under-resourced Indigenous communities so that they have the power to create their own dictionaries.

This includes a guide to different technologies available, so that communities can choose which approach might work best for them.

“That’s the whole purpose of the RelLex project, is to actually just give it back to the communities, and let communities lead on how they actually want their dictionaries to be made. And to break that stereotype: that it’s not up to the researchers, it’s really up to the communities, and that they can actually be the ones to create these.”

Honoured for Inclusion, Democracy and Reconciliation

On May 25 she was awarded for her efforts to include others by the governor general.

“I was honestly just shocked and speechless when I received the news. Afterwards I felt really honoured, mainly because I recognize this award not just for myself, but also for my community,” Aiyana said. “I share with my community because they’re the reason why I actually started my journey, why I worked so hard to be where I am. So I really share with them and my ancestors and just everybody.

“I think it’s just a symbol that as Indigenous people, we’re still here, we’re breaking down these colonial barriers.”

On the day of her graduation, when she received the medal from the governor general, she wore a tiara beaded by her great-great grandmother, Kyi·ku (Catherine Gravelle).

“I felt so much pride and honour wearing my great-great grandma’s tiara at my graduation, and I feel that she is looking down on me with happiness.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

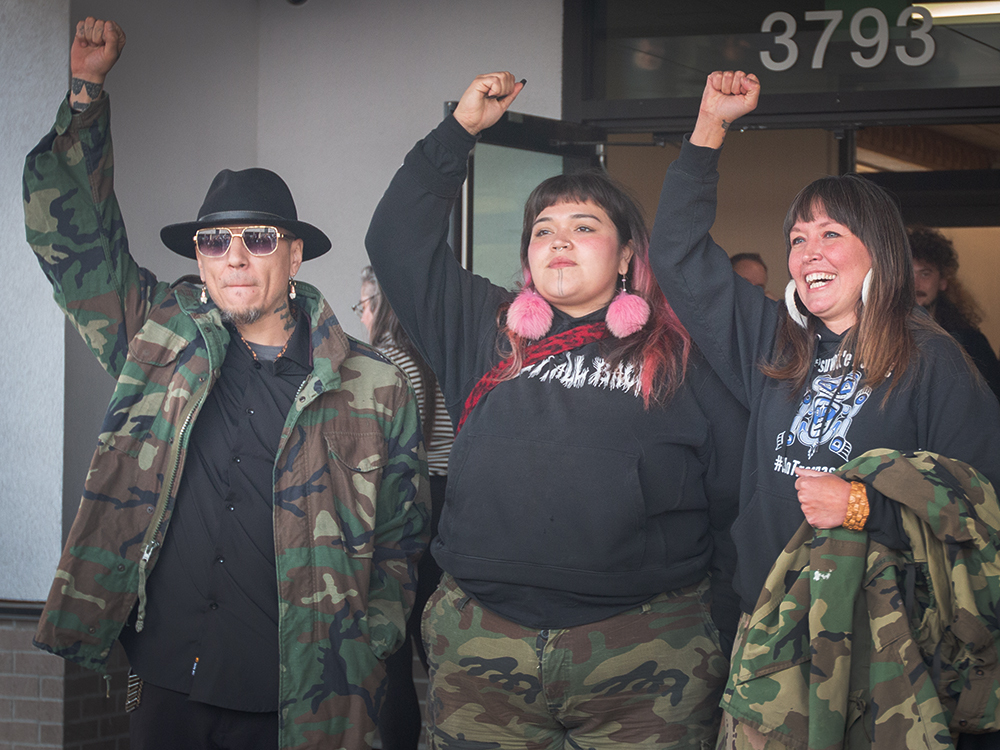

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

-

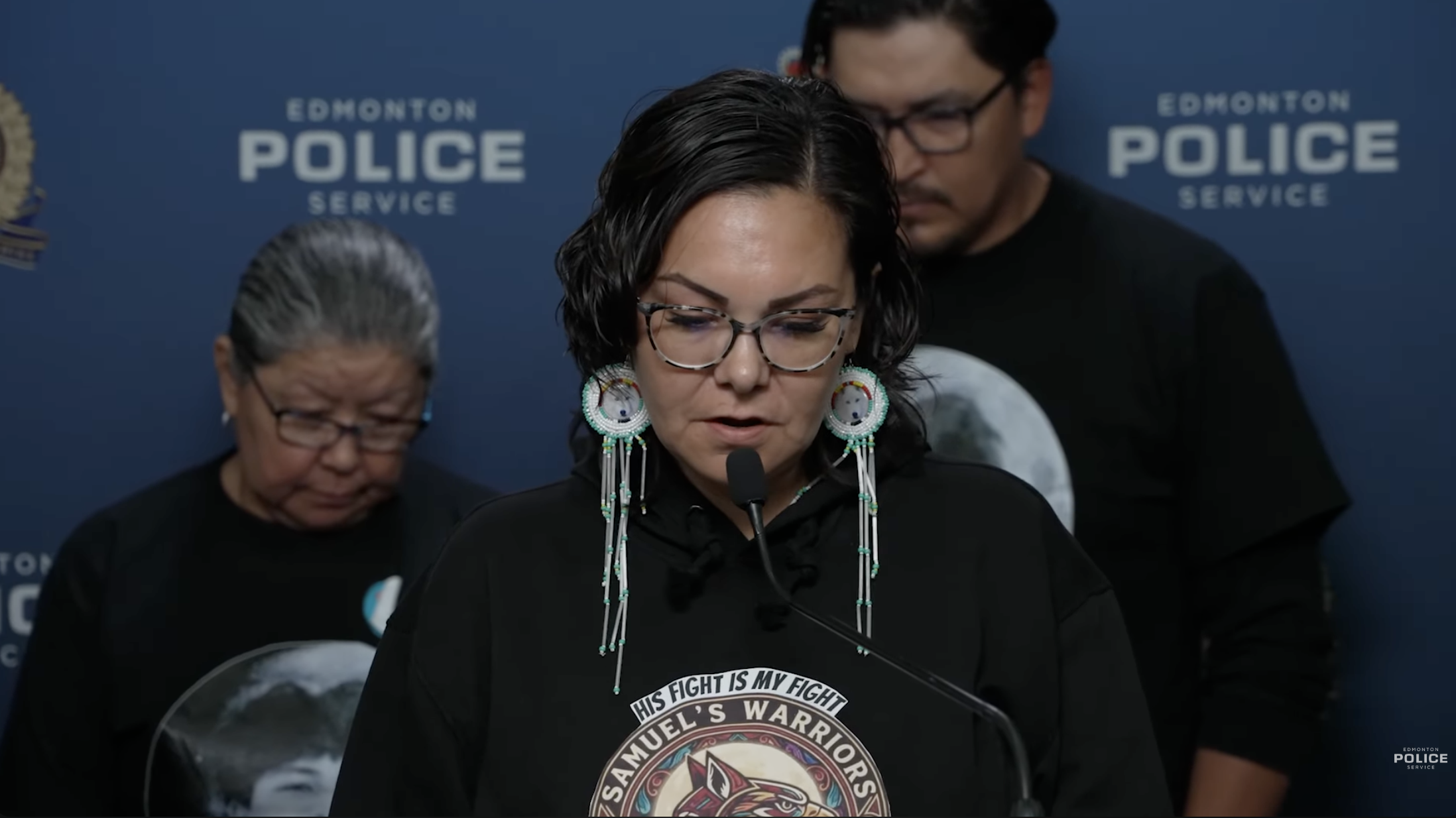

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death