Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous folks have more in common than I realized

How an Instagram story led to a surprising connection between two survivors of British oppression

When I shared a video to my Instagram stories, I expected a few laughs from my Caribbean followers. The video showed a young Black person running at top speed, with a dog closing in on him. The caption read, “You not Caribbean if this never happened to you.” My Bajan, Trinidadian, and fellow Jamaicans laughed along with me. Being chased by a mongrel (a street dog) is a quintessential Caribbean experience.

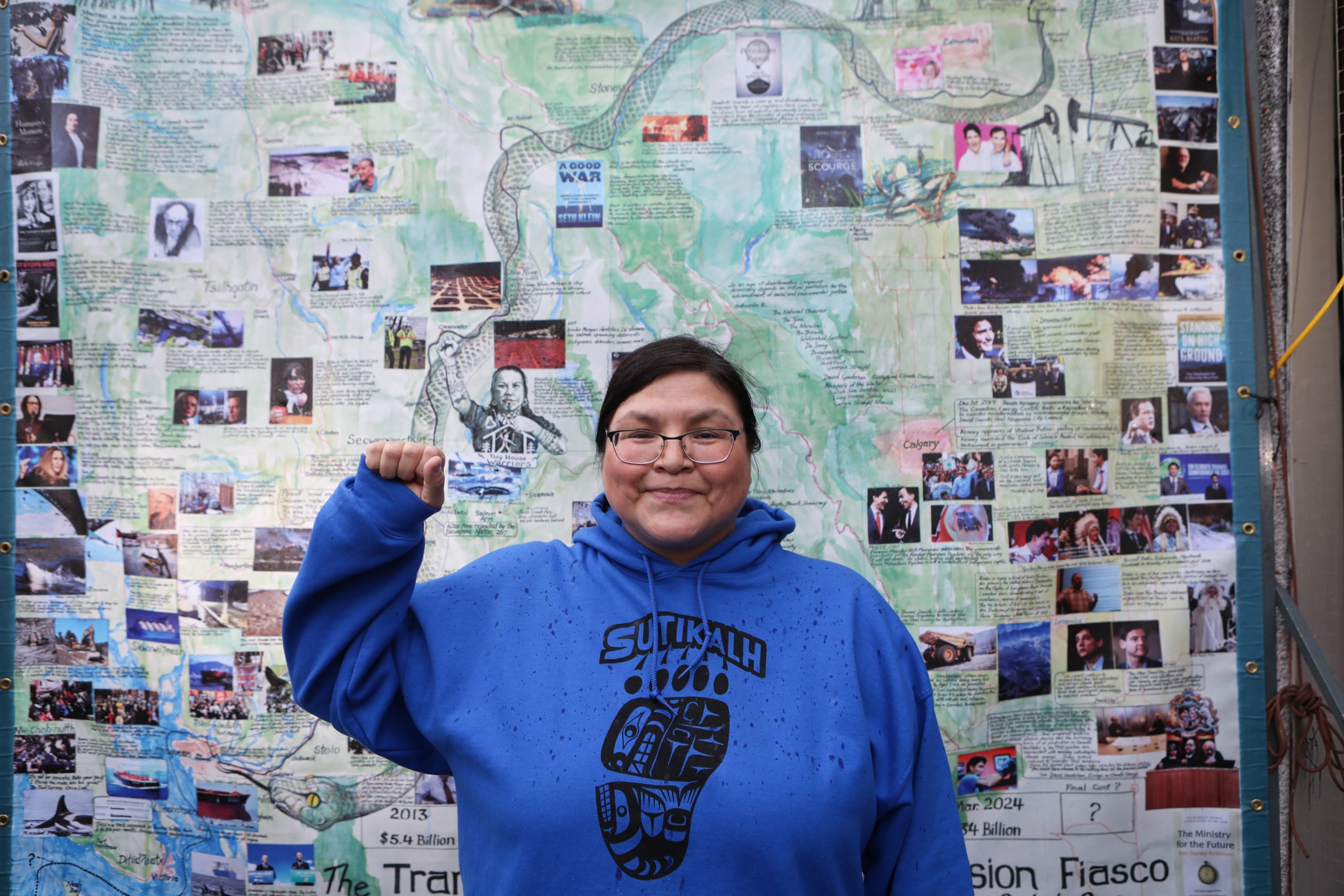

“Toronto” resident Theresa Cutknife, a Plains Cree woman who has lived in Maskwacis, let me know that this was also common on the rez.

I thought: “Wow. Thousands of miles away, and we had similar childhood experiences.” I wondered what else we had in common.

We were both colonized by the same people: the British in so-called “Canada” and Jamaica in the 1600s. Surely, there had to be some overlap in our histories and cultures.

So, I spoke with Cutknife about Indian time, and other things we could both relate to, as survivors of British oppression.

1. ‘Indian time’ and CPT (coloured people’s time)

Colloquially, Indian time and CPT both refer to our tendency to run late. But they are both rooted in a much more serious act of resistance against colonialism, capitalism, and the way whiteness is obsessed with time.

CPT came from resistance to slavery. The Lowcountry Digital History Initiative writes, “Common among the enslaved was working with slowness and performing carelessness to disguise their resistance as innocent mistakes, and this gave enslaved people some sense of self-determination, autonomy and independence.”

Indian time has a similar origin, born out of various Indigenous understandings of “time” before colonization. A study published by the Ecological Processes journal said, “The tribal understandings of time are defined by cues and patterns observed in the natural world. As such, time is then relied on, operated in, and based on a 3D construction rather than the westernized linear time system.”

“From what I know, Indian time is…if we’re meeting up to hang out, and we said, like, ‘We’re gonna meet at three o’clock.’ You hit me up and I’m like, ‘I’m on my way. I’ll be right there.’ Meanwhile, I’m very much in my house, not not making any type of moves. It’s very on your own time kind of thing. Always late,” said Cutknife.

CPT has many names across the diaspora, but it boils down to exactly what Cutknife described. Different “times” include African, island, and coloured people’s.

I was known as “the late friend.” I’ve had friends tell me to show up at 1 p.m. for an event that doesn’t start until 2 p.m., just so that I could arrive on time. Eventually, I learned to tamp down my tardiness. Now, I’m mostly “the on-time friend”, who shows up for birthday parties at the hour listed on the invite. These parties almost never start until hours later. Part of me wants to go back to being “the late friend” who runs on CPT!

After all, aren’t we simply honouring our ancestors by being late?

2. Our complicated relationships with Christianity, spirituality, and traditional religions

Christianity was a tool used to colonize Indigenous people. There are a number of Indigenous people who identify as Christian, despite the religion’s sordid introduction to “Canada.”

Jamaica is similarly a majority Christian country. There are Pentecostals, Baptists, Adventists, Anglicans, Roman Catholics, and more denominations. You name the branch of Christianity, and you will find it represented there. It is part of the unsavory legacy of British colonization.

Christianity is so prevalent that traditional African religions, such as Obeah, are feared and even criminalized. Some of our ancestors’ beliefs do slip through, like making sorrel for Christmas, using herbs for illnesses, or spinning around before crossing your house’s threshold (to ward off spirits, of course).

Cutknife said she saw similar habits of mixing Christianity and Indigenous traditions while growing up on her reserve. “There is a definite picking and choosing what serves you. I’ve been in multiple houses where you do have your medicine set up. But then you walked down the hallway, and there’s white Jesus there in front of you.”

3. The suppression of our languages

When enslaved Africans were brought to the Caribbean, they spoke different languages. In Jamaica, enslaved people spoke Igbo, Ga, and Wollof, to name a few. It is said that when different West African tribes landed in Jamaica, it was easier to learn Patois than English.

To this day, Patois is spoken by the majority of Jamaicans, even by those in diasporic Jamaicans in Canada, the U.K., and U.S. Even though the use of Patois is ubiquitous in the lives of Jamaicans, it is still highly stigmatized. There is still pressure for people to speak “proper English” to appear higher-class. The validity of Patois is hotly debated, and some wonder if it should be taught in schools and legally recognized as Jamaica’s official language.

“As most people know, residential schools were created and built to kill the Indian but save the child,” Cutknife said. “Language was not allowed in residential schools. You would be punished, you’d be beaten for speaking your language.”

Cutknife said both her grandparents were survivors of residential “schools.” They were not allowed to speak nêhiyawêwin. “As a result of that, there are many generations where the language was very much beaten out of our people.”

Though these aren’t the exact same history, the same colonial sentiment is identical: whether an enslaved African in the Caribbean, or a Cree child at a residential “school,” you were forced to assimilate, no matter the cost.

4. A continued sense of resilience

One thing all survivors of colonialism share is the spirit of endurance. The Indigenous population is growing at a faster pace than any other ethnic group in so-called “Canada.” Younger generations are taking to the revitalization of various languages, such as the nêhiyawêwin spoken by Cutknife’s grandparents.

In Jamaica, we will be celebrating our 61st year of independence this summer, and there are renewed talks of leaving the monarchy altogether.

Both our cultures have survived, despite the odds. I was inspired to write this because I believe there is much we can learn from each other. This entire continent was stolen from various Indigenous people, and built on the backs of millions of enslaved Black people. Our histories have always been intertwined, and it is high time we have this conversation. White supremacy would rather us not become allied. I hope this writing is a step in the direction of our renewed solidarity.

Author

Latest Stories

-

Inquest continues into Winnipeg police shooting death of Eishia Hudson, 16

Non-adversarial probe of teen’s death cannot assign blame, but family and First Nations hope it will recommend meaningful ways to prevent similar police shootings