Before it was the Highway of Tears: An excerpt from ‘Unbroken’

In the first chapter of her new book, Angela Sterritt reflects on the lineage of lands along the now-notorious stretch of road

Gitxsan is the name of my people on my father’s side. Translated to English it means “people of the river mist.”

As you travel the dewy highways and roads that ribbon the northwest of British Columbia, it’s clear why. Glacier-crowned mountains, misty zephyrs, and lush forests cradle the rushing waters from the Xsan (Skeena River) that runs along part of Highway 16 — now infamously known as the Highway of Tears.

The artery connects today’s Prince Rupert to Prince George and a number of Indigenous communities in between. It’s an area I’ve cherished since I was a young adult. I’d often pull my car over on the highway, just to listen to ravens smack their wings overhead, watch steelhead pop their gills out of the rapids, and feel the crisp air blow from the snowy mountaintops.

Nestled within the most northern reaches of the highway are six of my nation’s villages — Gitanmaax, Gitsegukla, Gitanyow, Kispiox, Gitwangak, and Sik-E-Dakh (Glen Vowell). These communities speckle our traditional territory — an area about five times the size of Prince Edward Island. Each distinct village is home to 400 to 700 people, or 800 to 2,500 if you include off-reserve members.

Some are graced with towering and intricately-carved totem poles, others are known for their summer rodeos, and still others boast peaceful mountainous landscapes. I am registered with Gitanmaax, a community born out of a tiny summer village first called Ansi’suuxs, or “place of the driftwood.”

In English, Gitanmaax (first called Git An Maa Hixs) means “people who fish with burning torches” and is rooted in our creation story about a woman who gave birth to part-human and part-canine children who eventually sustained the community with their unique fishing skills.

While it is the band I belong to today, my lineage stems from Kisgegas, a now abandoned village farther north. Both communities are about a 14-hour drive northwest from what is now Vancouver, or about five hours northwest from Prince George.

While those from far away may see these lands, near what is now known as the Highway of Tears, as merely characterized by danger and despair, we see them as so much more.

Oral histories and archaeological evidence show that my people lived in the northwest of what is now called British Columbia, building huwilp (house groups), families, and villages, at times struggling and at others thriving, for 10,000 years at least.

My childhood was filled with my dad’s stories of living at home in Gitxsan territory, of our culture, and of his travels. His tales helped me journey in my imagination to our rugged gentle lands of fireweed, red cedars, and rivers, absorbing our rich cultural history — much different from where I was born and grew up by the ocean in a small, largely-white town on Vancouver Island.

His stories instilled a curiosity in me about the expansiveness of the world, but also about how I belonged in it. Many of his narratives were of our Gitxsan relatives fighting to keep our land, our distinctiveness, and our relations, which in turn shaped my identity, knowing I would have to be brave and outspoken if I wanted a place in this world.

By age nine, I was captivated by the pieces of our culture he’d sprinkle throughout our conversations. He’d tell me stories about how the Gitxsan, Tsimshian, and Nisga’a once lived together in the northwest region as one people in an ancestral village known as Temlaham, long before they dispersed throughout the northwest. These stories were chronicles of a landslide and great deluge and how our nations built our communities back up after the natural disaster.

After long phone calls with his cousin, my uncle Neil Sterritt, my dad would tell me about our adaawk (oral history), which traces the history of our land told in pictures in formline designs carved on house fronts and in totem poles, and delineated through modern-day relationships.

When I was living in Prince George as a young adult, over emails, Neil would describe to me how our matrilineal lineage is connected to the lax gibu (Wolf Clan) and how, up until he died in 2019, his father, Neil Sterritt Sr., was Wiik’aax (“big wings”), the head of the House of Wiik’aax. It is a name and role my grandfather Walter Sterritt — Neil Sr.’s brother — was groomed for since he was a young man.

Neil Jr. said foot messengers used to bring my grandfather small gifts as he was being raised to fill the leadership role. But Grandpa decided to focus on his family and work rather than become the miin wilp (head) of the House of Wiik’aax, and eventually Neil Sr. (after once declining) agreed instead.

These stories learned from my dad and uncles are ones I hold close to my heart, since my grandfather died before I was able to process memories, when I was a baby. Uncle and Dad shared that our Gitxsan trickster, or transformational figure, Wiigyet, created our natural world of rivers, oolichan runs, and light and darkness — in folly, spite, and pure selfishness.

In my younger years, I was not taken by these stories, which often seemed long-winded rambles. I didn’t relate to their clever and philosophical messages until much later in life. But they gave me a sense of the creative wisdom of our people and inspired the curiosity and imagination that would later draw me to visual art, literature, and storytelling.

Wiigyet is said to be craft without wisdom, and power without any regard for consequences. To me, Wiigyet holds up a mirror to us, making fun of the weaknesses that make us human.

As I got older, I became more enamoured of these stories, and my thirst to learn grew. When I lived on the street, they became a metaphor for survival; they reminded me that even in chaos, with ingenuity and acceptance of the ever-changing world around us, anything is attainable.

If not a teacher, Wiigyet pushes us to ask questions about our intentions and to laugh at ourselves when it all stops making sense. The tales also taught me about myself, and about my Gitxsan culture — one that puts our women at the centre of everything.

My uncles didn’t share much with me about the roles of our women, other than that we are a matrilineal society. But I later learned much more from Gitxsan women and Elders while living in Prince George and in Vancouver.

Adapted with permission of the publisher from the book ‘Unbroken: My Fight for Survival, Hope, and Justice for Indigenous Women and Girls,’ written by Angela Sterritt and published by Greystone Books in May, 2023. Available wherever books are sold.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

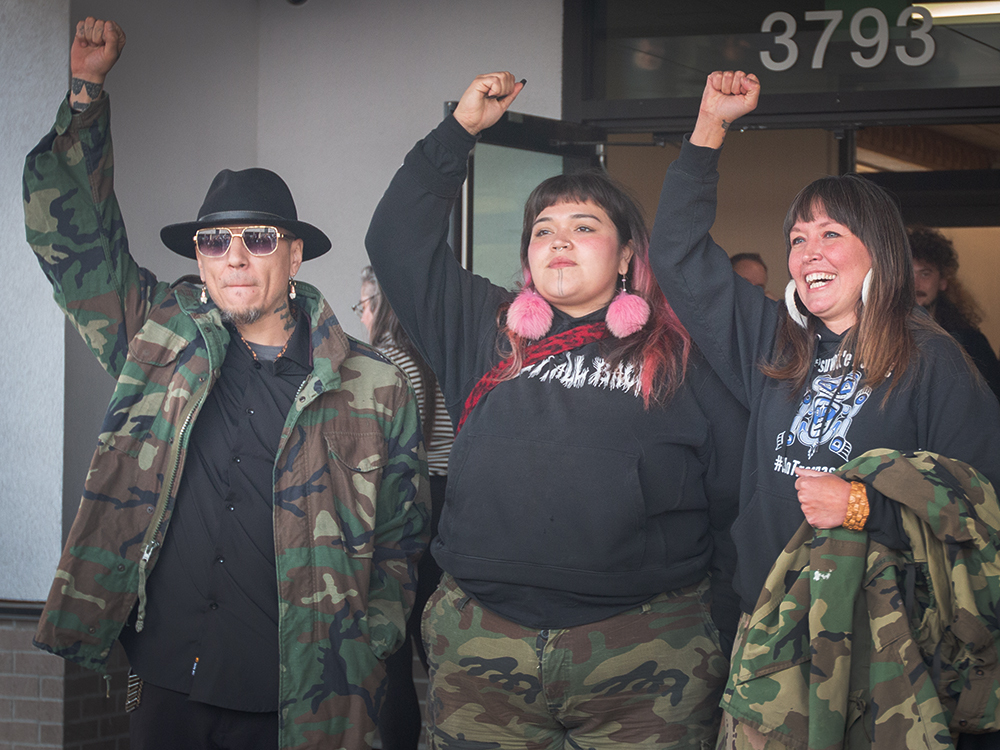

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

-

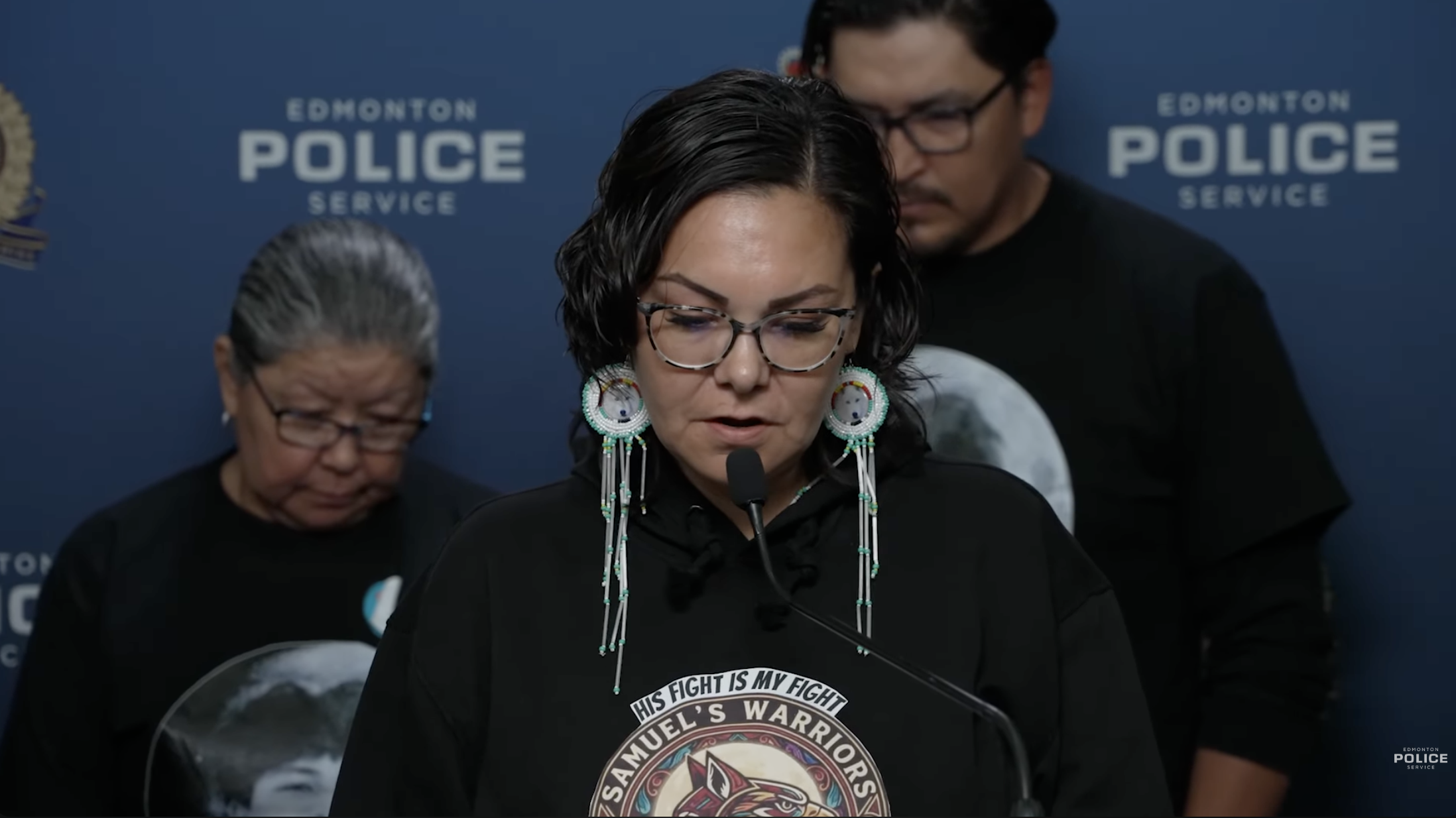

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death