The weaponization of the courts should concern us all

Injunction laws aren’t about justice, writes environmental campaigner Christine Thuring, but facilitating the exploitation of stolen land

In October of 2020, I travelled with others from Coast Salish territories to Tk’emlúps (Kamloops) to support Indigenous water protectors standing up against the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion (TMX).

While at the construction site at Sqeq’petsin, I witnessed Secwépemc Matriarch Miranda Dick post a “cease and desist” order — stating that TMX was not permitted to drill under the sacred waters briefly known as the “Thompson River.”

While Dick was conducting a hair-cutting ceremony beside the gate, her foot was a few inches over the RCMP’s freshly-drawn injunction line.

Along with seven others, Dick was arrested for breaching the TMX injunction and “contempt of court.”

During two years of hearings, the judge who convicted the Secwépemc water protectors has disregarded the significance of ceremony — held on their own territory and in accordance with Secwépemc law, to protect women, water and future generations.

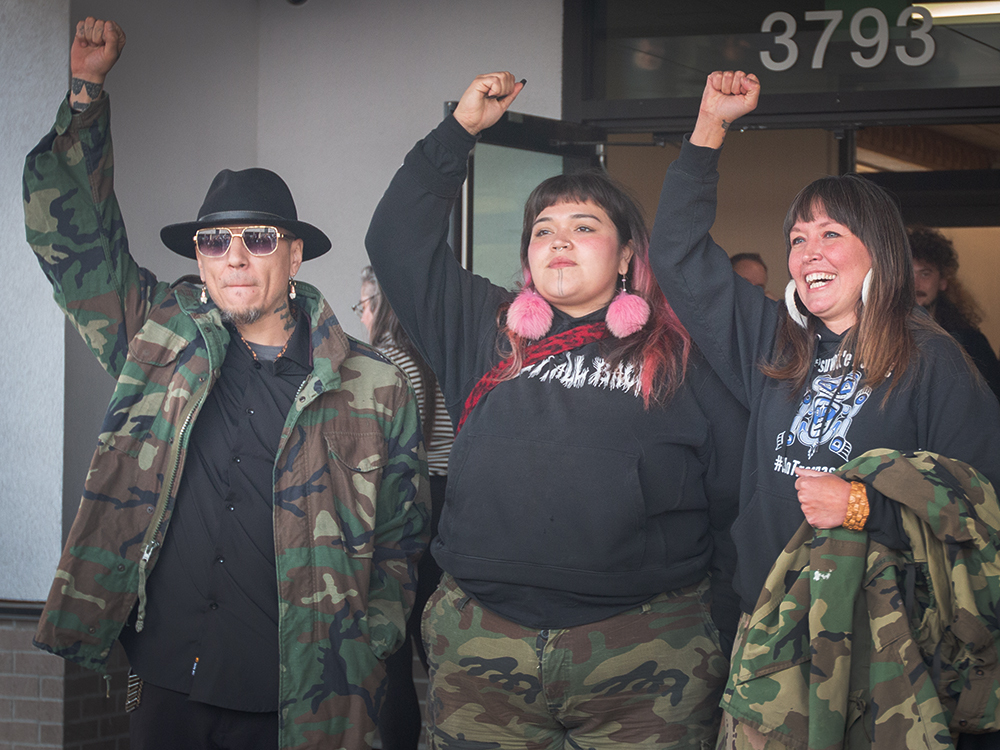

Last month, Miranda Dick and five others, including a hereditary chief, were each sentenced to a minimum of 28 days in jail.

It wasn’t always so risky to protest the pipeline — but we have seen an escalation in this type of punishment through the courts since 2020.

There seems to be a particular harshness towards Indigenous people in our “justice” system — exuding a colonial toxicity that has no place in an era of “truth” or “reconciliation.

TMX and the injunction that shields it

Court-ordered injunctions are used to legitimize the repression of political resistance and to criminalize any opposition to corporate and government agendas.

While injunctions have been used against Indigenous people for centuries, they’ve become more prevalent in recent years consistent with the rise of neoliberal capitalism and privatization.

The beneficiaries are companies and governments, which are able to use the court to protect their interests based on an inflated definition of “harm” usually accepted by the court.

Back in 2014, hundreds of people united in opposition at the pipeline’s terminus on “Burnaby Mountain.” More than 100 people were reportedly arrested, but those charges were ultimately all thrown out because of inaccurate GPS coordinates.

In March 2018, Tsleil-Waututh Nation built the Kwekwecnewtxw (watch house) adjacent to the TMX storage tank facility, in order to keep an eye on the pipeline terminus. Will George (Swaysən) was the first guardian of the space.

Days later, Trans Mountain was granted a court-ordered injunction to stifle resistance.

Growing political uncertainty led the Texas-based Kinder Morgan to abandon the project, and “Canada” bought TMX for $4.5 billion in August 2018.

As such, TMX is now owned and regulated by the federal government and its agencies, which some see as a serious conflict of interest.

The colonial legal system comprises Crown and court: the Crown decides whether to target and charge land defenders, and the judges have the final word.

In late 2019, B.C. Supreme Court Justice Shelley Fitzpatrick started overseeing TMX injunction cases.

I’ve observed an escalation of sentencing severity under Fitzpatrick, which illustrates the court’s compliance with Crown’s strategy of deterrence.

I’ve sat through several court sentencings under Fitzpatrick, whose sarcastic, paternalistic behaviour is not what I expected from a judge.

In the hearing for Tsleil-Waututh land defender Will George, who breached a TMX injunction on “Burnaby Mountain,” Fitzpatrick revealed that she did not know where Tsleil-Waututh territory was — even though both the courtroom she was sitting in and the TMX terminus are located on the nation’s shared lands.

Fitzpatrick sentenced George to 28 days in jail, much to the concern of his community, whose leadership has been opposing TMX for years. He is currently behind bars, after his appeal was rejected.

It is disturbing to witness such power wielded by a judge with such an evident gap in knowledge about — and blatant disregard for — Indigenous history.

Facilitating exploitation

Our courts have been weaponized through injunction law to oppress sovereign Indigenous nations and to suppress public opposition to extractive industrial projects.

For Indigenous land defenders, following ancient laws and upholding their duties to future generations, the courts are as ruthless as their colonial foundations.

As a consequence, we’re seeing our jails and courts swelling with land and water protectors — many of whom have been terrorized by C-IRG, an expensive, mercenary branch of the RCMP.

We’re seeing Indigenous Peoples being criminalized for protecting their unceded lands by a draconian colonial legal system.

Similar to the Potlatch Ban, the courts are weaponized to target Indigenous culture and ceremony. Judge Fitpatrick has consistently refused to acknowledge unceded territory and Indigenous laws. In some cases, she declined to use the Indigenous names of defendants — although she did eventually begin to use Secwépemc Hereditary Chief Sawses’s Indigenous name.

At Kwekwecnewtxw in 2020, Jim Leyden and Stacy Gallagher conducted a pipe ceremony for 20 RCMP officers and were both arrested days later. Gallagher was given a 90-day jail sentence.

Injunction law demands that the court ignore “Canada’s” commitment to “free, prior and informed consent” under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP).

Injunction law triggers the court to criminalize nonviolent protest and propagate trauma, while permitting industry to destroy land, homes and communities.

These court cases are not about justice nor even about upholding “rule of law” — they’re about facilitating the exploitation of stolen land. Such trends should concern anyone who values democratic process, human rights, and how tax dollars are spent.

Publishing this opinion piece was made possible in part through a grant from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Youth connect to their lands — and relatives — with annual Rez Ride

The Menmen tl’a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh mountain bike team pedals through ancestral villages — guided by Elders, culture and community spirit

-

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests