Annual Spirit of syilx Youth Unity Run begins with honouring of residential ‘school’ survivors

More than 100 syilx youth gathered at the site of the former residential “school” to kick off this year’s run

Content Warning: This story contains content about Canada’s residential “schools”, child death, and the following impacts such as poverty and suicide. Please read with care. syilx unity run

On June 3, for the first time in its 14-year-history, the annual Spirit of syilx Youth Unity Run departed from the Kamloops Indian Residential “School” in Secwépemc territory.

This year’s starting location was the end point of last year’s run.

“It was about a year ago that we ran from Vernon to here, to honour 215 and all the residential school survivors, intergenerational survivors and those who are continuing to go through the healing process together,” said Jordan Coble, a Westbank First Nation councillor who was in attendance with his kids.

“It’s an honour to be here today so that we can return that spirit, the same idea that we had that we brought here [last year, we will now] bring it back to our home communities and make sure that the spirits of these children make it home, making sure that their Elders and their relatives know that we’re doing the work that honours their legacy, honours our work together.”

More than 100 syilx youth gathered at the site of the former residential “school” to kick off this year’s run, which saw participants traverse nearly 300 km from Secwépemc territory and through syilx territory over a three-day span. The finish line was at the Penticton Indian Residential “School” monument on June 5. Prior to the run, youth were invited to touch the monument at the Kamloops Indian Residential “School” in honour of the children they were running for.

The run has served as a means for youth to raise awareness around violence and suicide in the syilx Nation, as well as an opportunity for youth to come together to explore their territory and its different teachings.

Kwelaxen Louis, an 18-year-old syilx Youth from the Lower Similkameen Band, said that he’s participated in the annual run “for as long as he remembers.”

“I’m here to spread awareness about suicide and violence within Indigenous communities,” he said. “It’s nice to be a part of something, spreading awareness.”

c̓ʔak̕ʷm Jennifer Lewis, event organizer, and wellness manager of Okanagan Nation Alliance, said that starting at the Kamloops Indian Residential “School” was also a way to honour syilx Nation members who had attended the “school.”

“It’s really a show that we are still here. puti kʷala – we are still here. And that we’re strong, that we’re going to honour the survivors that were able to survive and then those that attended that weren’t able to come home [for] various reasons,” Lewis said.

“There’s children buried, but there’s a lot more that will never be found because of different ways that they were murdered. We just honour all of those spirits and all of our people that came here.”

Lewis said that acknowledging the history and harm of residential “schools” helps Youth understand the present-day realities of Indigenous families and communities.

“Why families are the way they are and why there’s so much disproportionate chronic conditions of violence, suicide, overdose and poverty. A lot of it stems from Indian residential ‘school’,” she said.

syilx Elders were also in attendance, including skəltia Hazel Squakin, a Survivor of the Kamloops Indian Residential “School,” who shared her experiences as a former “student” with those at the gathering.

Members of the Secwépemc Nation, whose land the Kamloops “school” is located on, were also in attendance. Many shared their hand drum songs.

Coble told the hosts that he was grateful to be welcomed on their territory.

“Thank you very much for allowing us to be on your lands to start our journey here today, to continue our shared journey,” said Coble. “We’re all sqilx’w here, we’re all Indigenous people, we’re all from these lands.”

Lewis said that she hopes youth participating in the run were able to see all the Helpers around them as they went along; the air, the trees and the medicine that gives them life.

“Our energy meets the energy of the land and all of these living things we come across. It’s hard to describe to mainstream society because they don’t understand why it’s important,” she said. “But it’s at a spiritual, soul level. That’s why it’s so important.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

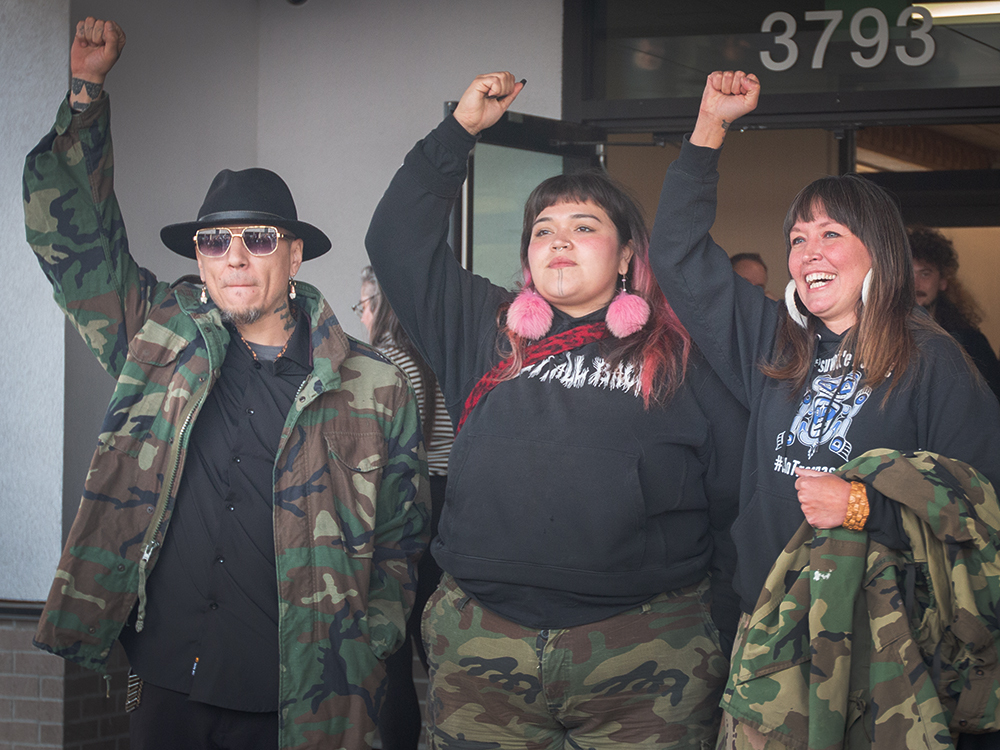

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

-

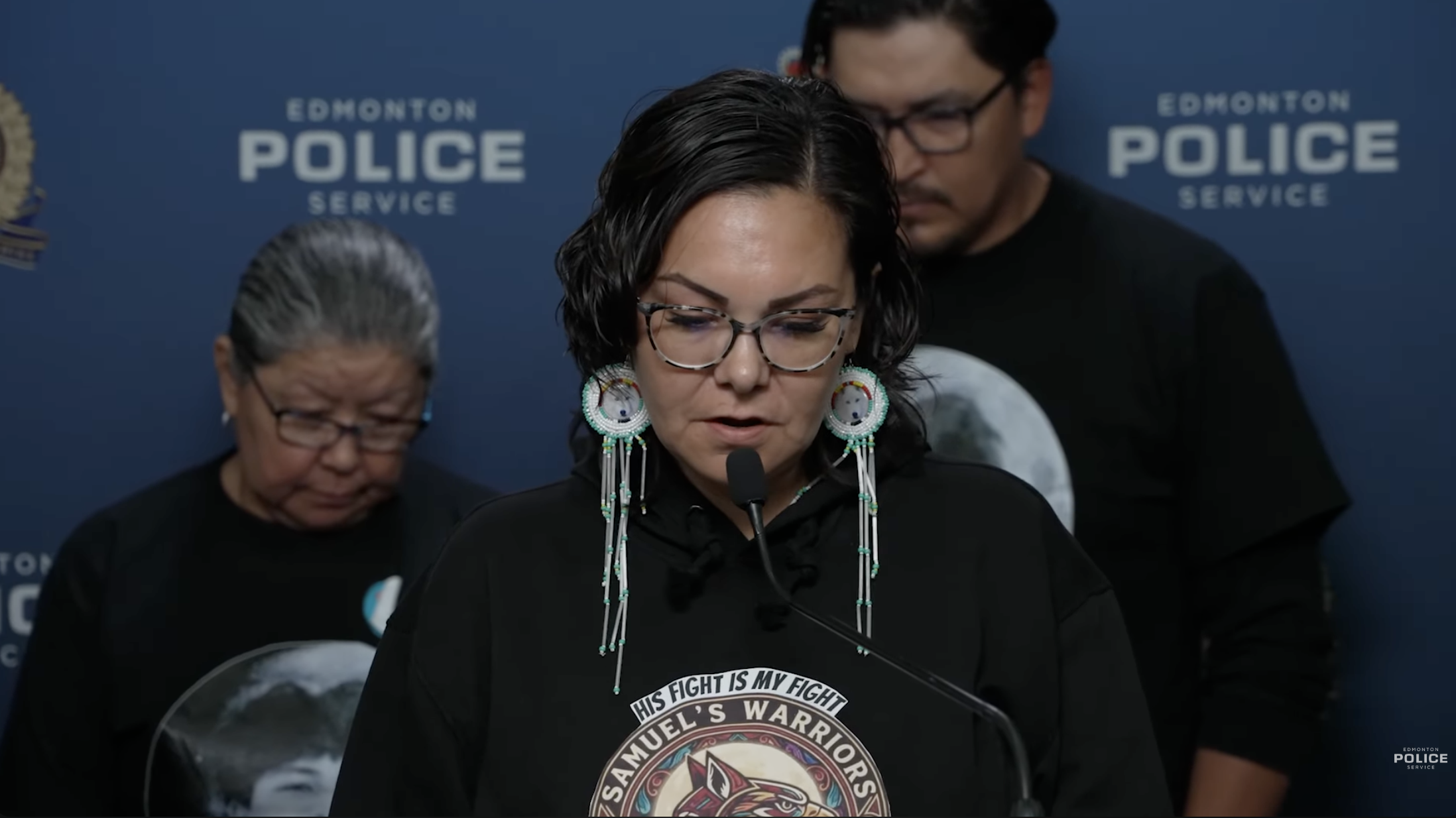

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death