Expanse of deep ocean off ‘Vancouver Island’ set to become protected area

First Nations and federal government sign MOU to co-manage proposed MPA in 133,019-square-km section of the Pacific

A massive swath of deep ocean off “Vancouver Island” is set to become the second-largest Marine Protected Area (MPA) in the country, after an agreement was reached between surrounding First Nations and the federal government.

On Tuesday, leaders from the involved parties — the Council of the Haida Nation, the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Pacheedaht First Nation, Quatsino First Nation and “Canada” — announced they had signed a memorandum of understanding to co-manage the proposed MPA.

The 133,019-square-km section of the Pacific Ocean — about four times the size of “Vancouver Island” itself — contains more than 46 underwater mountains and rarely-found hydrothermal vents.

The proposed MPA is being called “Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxwiqak — Tsig̱is.” It’s located more than 80 km off the coast of Haida Gwaii, and on-average 150 km off the west coast of “Vancouver Island.”

“This area is remarkable,” said Fisheries Minister Joyce Murray during the announcement at the IMPAC5 conference on Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh territories.

“These are the only known hydrothermal vents to exist in Canada’s waters.”

The vents, she explained, are also significant because they support many species such as tubeworms and deep-sea clams. The area was first identified as a potential MPA in 2017.

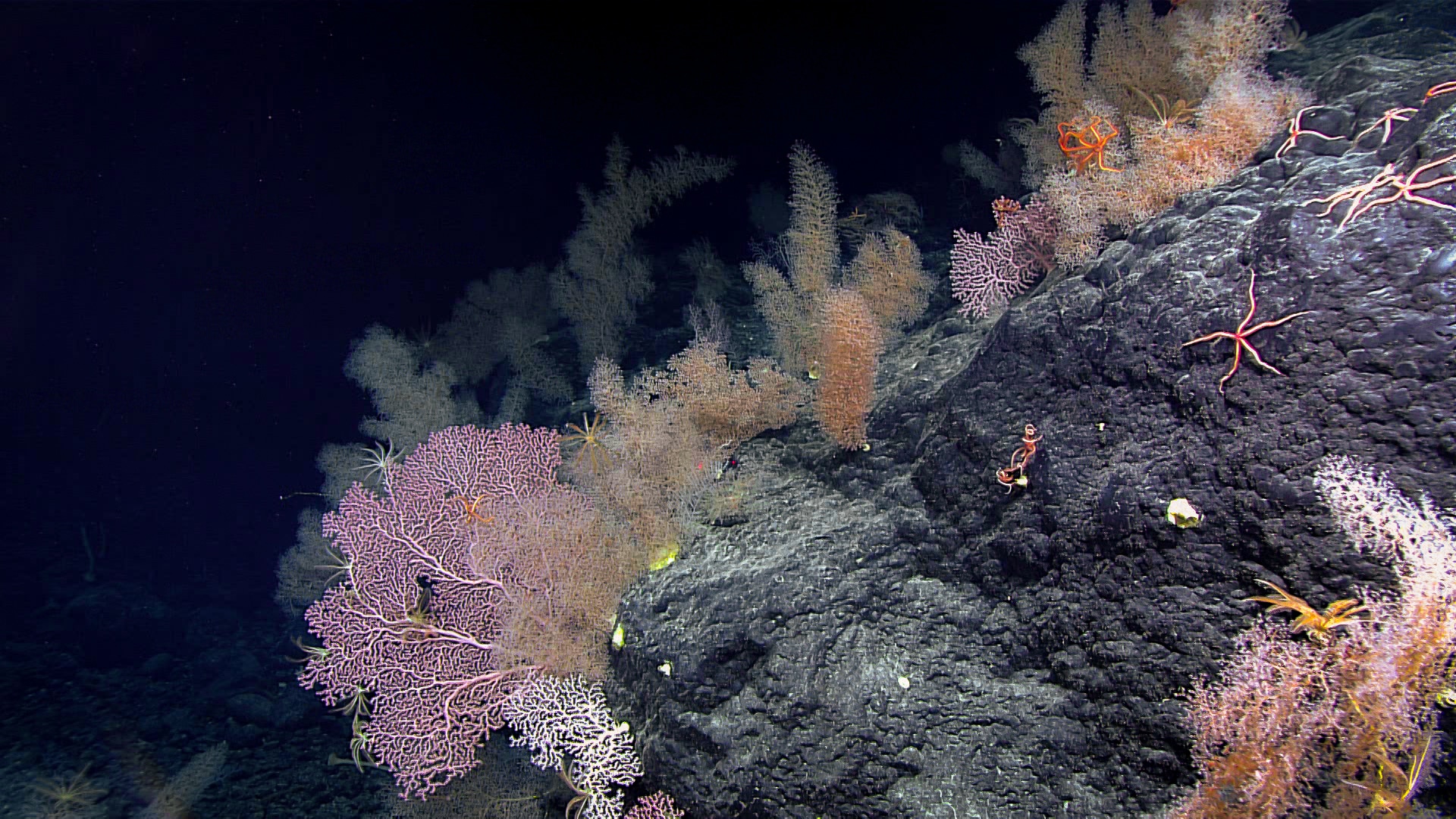

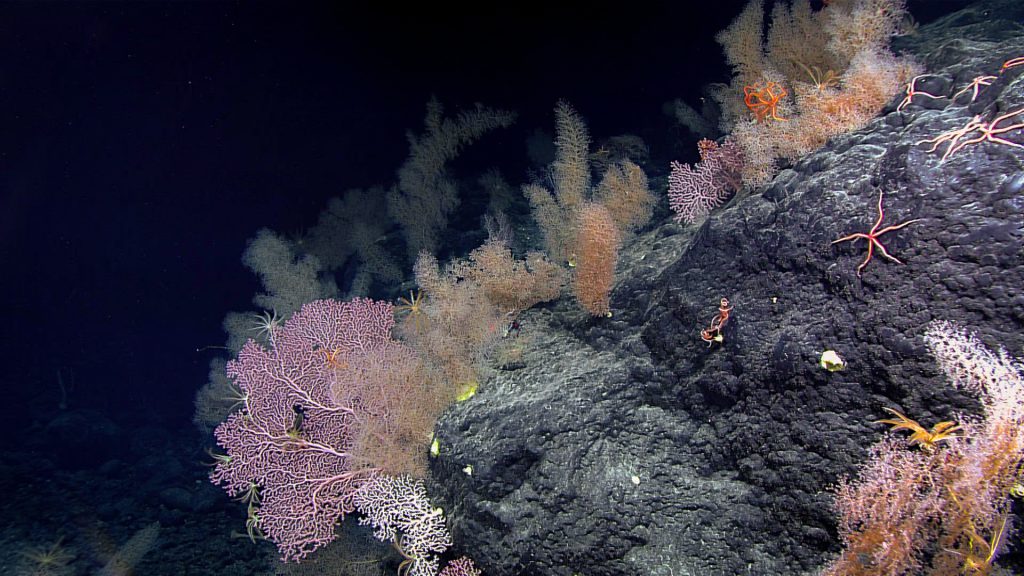

The ocean conservation group Oceana Canada was part of an exploration of the area in 2018, which revealed the existence of “centuries-old forests of red tree corals and glass sponges that provide habitat for numerous animals, including sea lilies, basket stars, octopuses, prowfish and many long-lived rockfish,” it said in a statement.

“Above the seamounts, the upwelling of deep nutrient-rich water fuels the growth in planktonic life that attracts larger species such as tunas, sharks and whales such as humpbacks, as well as seabirds including tufted puffins.”

Gaagwiis Jason Alsop, president of the Council of the Haida Nation, said the surrounding First Nations and “Canada” have been working together for about five years towards establishing an MPA, for which this agreement is an important step.

As an MPA, which is a designation under the federal Oceans Act, the area would have increased restrictions and protection against invasive activities such as deep sea mining, oil and gas activities and other extractive work.

Draft regulations for the proposed MPA are expected to be made available on Feb. 18, after which they will be subject to a 30 day public comment period. After that, the federal government will make its final decision on whether to establish the MPA.

“It’s really significant and powerful the work that’s taken place … to get us to this place where we can all look after this large part of the ocean together, each under our own respective authorities,” Alsop said.

The name, Alsop added, is significant. It consists of a Haida word meaning “deep ocean” (Tang.ɢwan), a Nuu-chah-nulth and Pacheedaht word meaning “deepest part of the ocean” (ḥačxwiqak) and a Quatsino word referring to a “monster of the deep” (Tsig̱is).

“I think it’s really worth noting and celebrating what we’ve been able to do here in naming this Marine Protected Area in our Indigenous languages,” he said.

“Each describing the deep ocean and our connection, our deep connection, to these ancestral places that each of our nations before you today hold.”

He said eventually, the nations will seek to give names to each of the 46 underwater mountains, called seamounts. Judith Sayers, president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, reiterated that Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxwiqak — Tsig̱is is a significant marine site, rich with habitat and biodiversity.

“There are many spiritual places there, a lot of sea-life goes through there,” she said.

“So today, we aren’t the only ones who are celebrating, our relatives in the ocean are celebrating.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Truth, courage, care’: Esk’etemc leader honoured with ‘B.C.’ reconciliation award

Charlene Belleau has been ‘leading voice’ of justice for survivors — documenting truth and supporting community healing

-

Across the border, Indigenous fears spike amidst ‘U.S.’ immigration crackdown

With ICE operations, multiple First Nations warn members about travel risks — despite treaty rights. Why Indigenous communities are on the frontlines defending rights for all