Indigenous mother ‘tired of fighting’ after human rights tribunal victory challenged by VACFSS

The child welfare agency was ordered to pay $150K for discrimination against ‘Justine’ — but it’s now asking the B.C. Supreme Court to toss out that decision

The Vancouver Aboriginal Child and Family Services Society (VACFSS) is challenging a ruling which ordered the agency to pay $150,000 to an Afro-Indigenous mother whose daughters were placed into foster care.

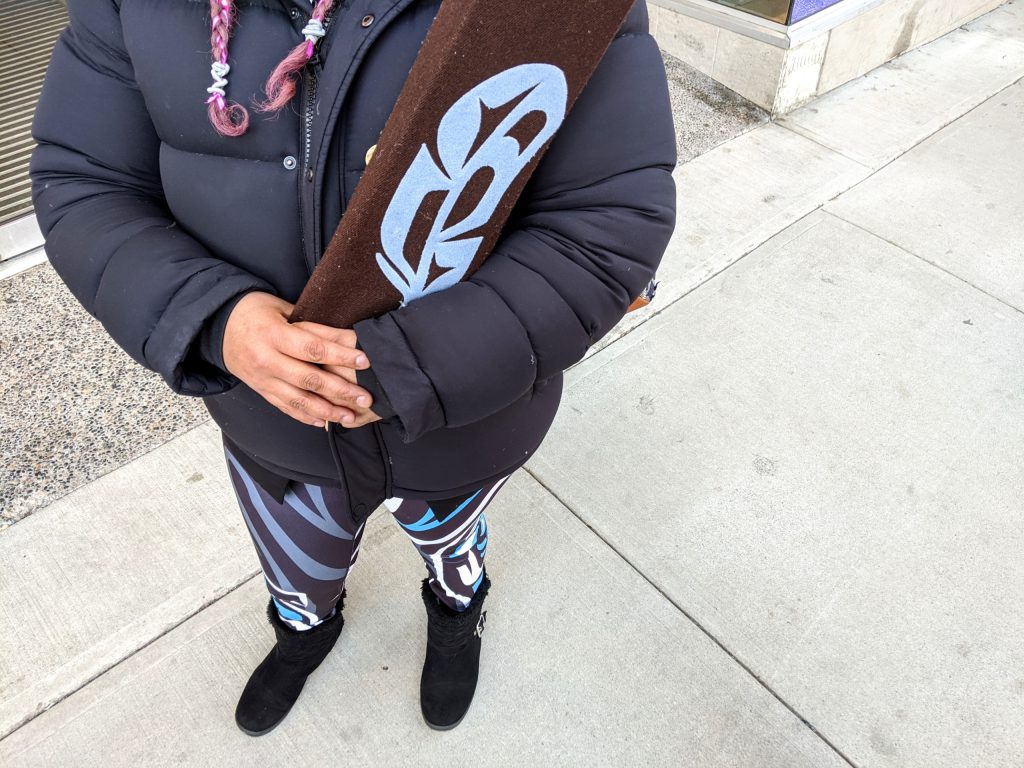

In November, the B.C. Human Rights Tribunal found VACFSS discriminated against Justine — whose real name is being withheld to protect her children’s privacy — based on her Indigeneity and disabilities, violating the B.C. Human Rights Code.

Now, VACFSS — an Indigenous-led agency delegated by the province to serve Indigenous families — is asking the B.C. Supreme Court to review the tribunal’s decision and consider tossing it, along with the award it was ordered to pay Justine “as compensation for injury to her dignity, feelings and self-respect.”

VACFSS is clear in its petition that it’s not trying to “challenge [Justine’s] lived experiences as an Afro-Indigenous mother.” But to Justine, this feels “personal.”

“I’ve put a lot of years into this, since 2016 … It’s stressful. It’s exhausting,” she says. “Now they’re going to fight us in court all the way to the Supreme Court. It’s like, when are they really going to start working with the families?”

Tribunal strayed beyond its jurisdiction, says VACFSS

In 2016, social workers from VACFSS removed Justine’s four daughters and placed them in three different foster homes. After a lengthy court battle, her children were returned to her in 2019. Meanwhile, in 2017, Justine filed a complaint with the tribunal.

The case, by all accounts, is complicated, and the tribunal spent three weeks hearing it (over the course of 17 months) before arriving at a decision on Nov. 22, 2022.

“VACFSS’s decisions to retain custody and restrict [Justine’s] access to her children were informed by stereotypes about her as an Indigenous mother with mental health issues, including trauma, and her conflict with the child welfare system,” wrote tribunal member Devyn Cousineau in a 147-page decision, which Justine’s lawyer called “precedent-setting.”

On Jan. 23, VACFSS filed a request for “judicial review” of the decision.

In its petition to the court, VACFSS claims the tribunal tried to “make legal determinations on matters of custody and access that fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the British Columbia Provincial Court.”

It claims that Cousineau didn’t administer the case fairly — expanding “the tribunal’s jurisdiction and/or the scope of the complaint” without “providing proper notice” to VACFSS.

Jonathan Blair, a lawyer with the nonprofit law firm CLAS, is acting for Justine in the case. He explains that VACFSS is essentially saying that the B.C. Human Rights Tribunal shouldn’t step in on child custody issues.

“And, of course, no one is saying that they should make child custody decisions,” he says. “But to say that they can’t come in when there’s been discrimination in a child’s custody matters seems absolutely bizarre.”

It’s an especially “surprising” position for an agency that purports “to eliminate oppression, discrimination and marginalization within our community” as part of its “philosophy of service delivery,” he adds, referencing the VACFSS website.

In a statement released on Jan. 24, VACFSS board chair Linda Stiller says that requesting a judicial review was “essential” because the human rights tribunal “overstepped its jurisdiction.”

“We understand that this step is very difficult, but it is necessary to ensure Indigenous children are protected as intended by the legislation,” says Stiller.

Ultimately, the agency “regrets having to file a judicial appeal on this case, particularly as an Indigenous-led agency committed to restorative practice and the advancement of provisions in the Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families,” she adds.

In its petition, VACFSS argues that the $150,000 award was “patently unreasonable.” If the court doesn’t toss out the whole decision, VACFSS is asking it to either come up with a new number or order the tribunal to do so, and to stay — or put a hold on — the compensation order in the meantime.

“They’re saying we shouldn’t have to give her so much money,” Blair says. “Even if it was correct to find that they discriminated … That, to me, is disingenuous with the way they’re framing their petition to try and say, well, this is just about jurisdiction and the protection of Indigenous children.”

Blair says Justine will likely have to wait at least nine months for a decision from the Supreme Court — which has yet to schedule a hearing. “The fastest you could expect would be like a hearing in May, and then a decision within like five or six months after that.”

He points out that if the court rules in VACFSS’s favour, Justine may very well “have to go through another very tiring and emotionally-devastating hearing.”

“The normal remedy is that it actually goes back to the tribunal for another hearing,” says Blair. “So there’s no aspect of this that’s in the best interest of [Justine] or her children.”

‘I’m tired of fighting. I just want to live in peace.’

Justine says she wishes things would move faster, and she’s just glad to have her children with her, as opposed to in foster care. She’s moved them out of “Vancouver” to be closer to her stepfather and aunt in “Chilliwack.”

Asked about her plans for the $150,000 award, assuming it’s still forthcoming, she says her first priority is taking her girls on a trip.

“I want to ask them what they want to do. Where do they want to go? Of course, they’re probably going to say Disneyland or something like that,” she says, laughing.

She says she’d also like to buy her stepfather a new trailer.

“He’s 88 years old. I would like for him to live at home with me but he’s an Elder and has his own land that his mother owned, and his grandparents owned, and he kind of wants to be there, so I want to make sure that he’s got a warm trailer because it’s not even properly insulated.”

Beyond that, she says she’s dreaming of starting up a little family business, maybe something in the cooking industry. In the meantime, she’s just trying to get by.

“We’ve been suffering and struggling for so many years,” she says. “Every day I still have anxiety sending the kids to school. I know they’re fine … [it’s] just anxiety [after] everything that I’ve been through.”

“I’m tired of fighting,” she says. “I just want to live in peace.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

Children’s book tells residential ‘school’ story from a kid’s perspective

‘Shirley: An Indian Residential School Story’ — released today — was written by Joanne Robertson with, and about, Elder Shirley (Fletcher) Horn