Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

This story was originally printed in The Tyee and appears here with permission and minor style edits.

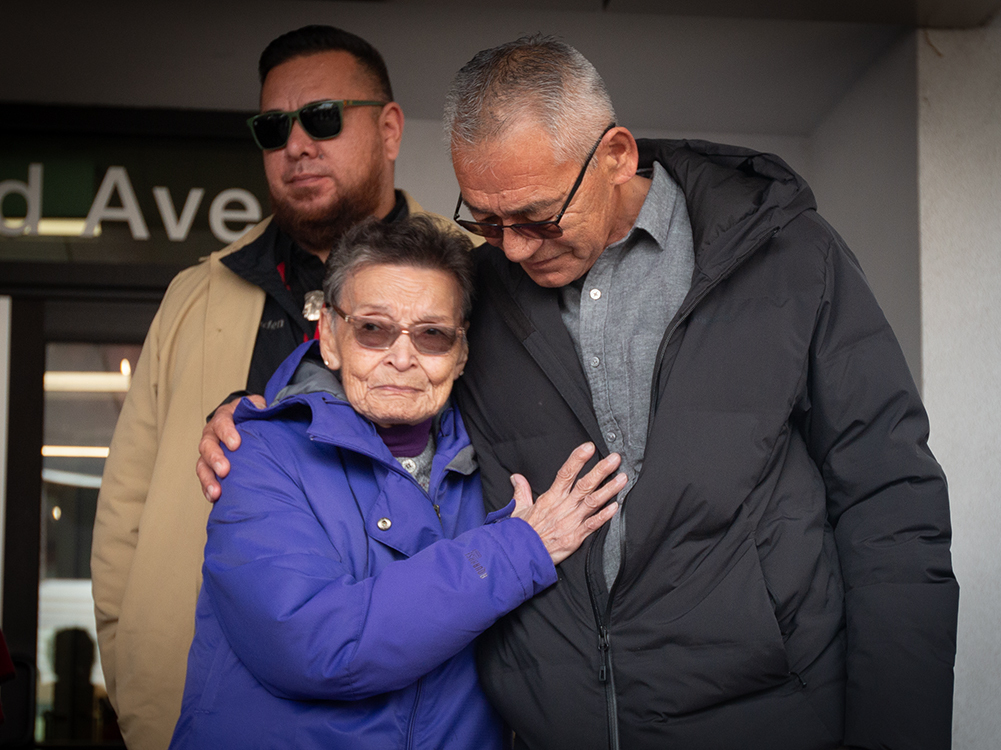

About 100 people packed into the “Smithers” courthouse on Friday to show support for three Indigenous land defenders being sentenced for attempting to halt work on the Coastal GasLink pipeline in 2021 in defiance of a court-ordered injunction.

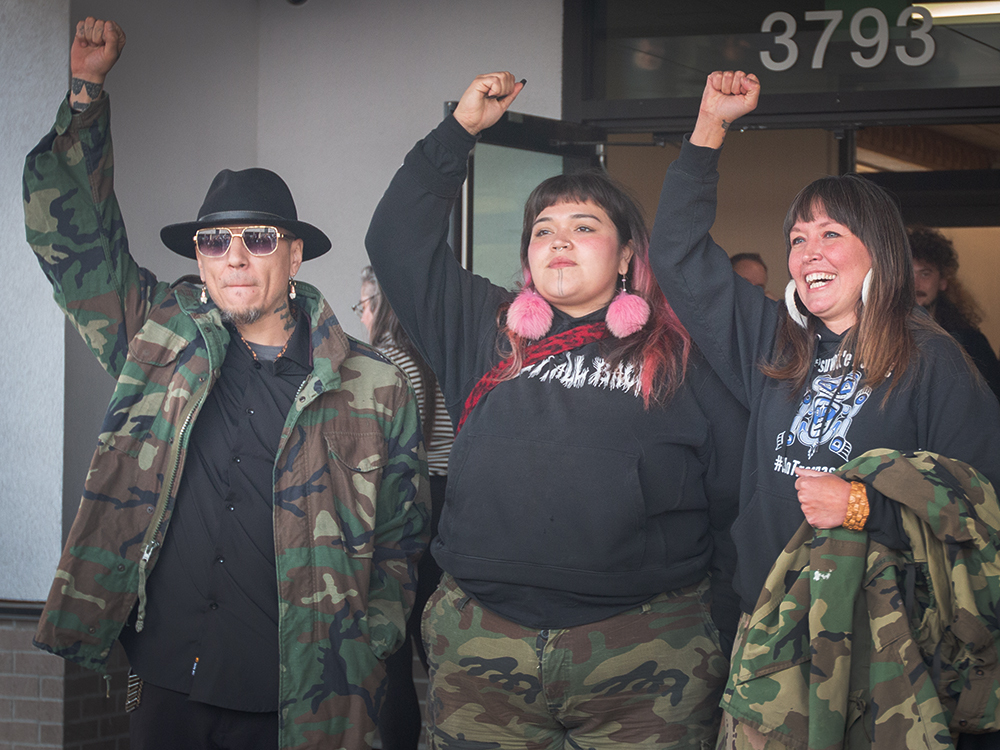

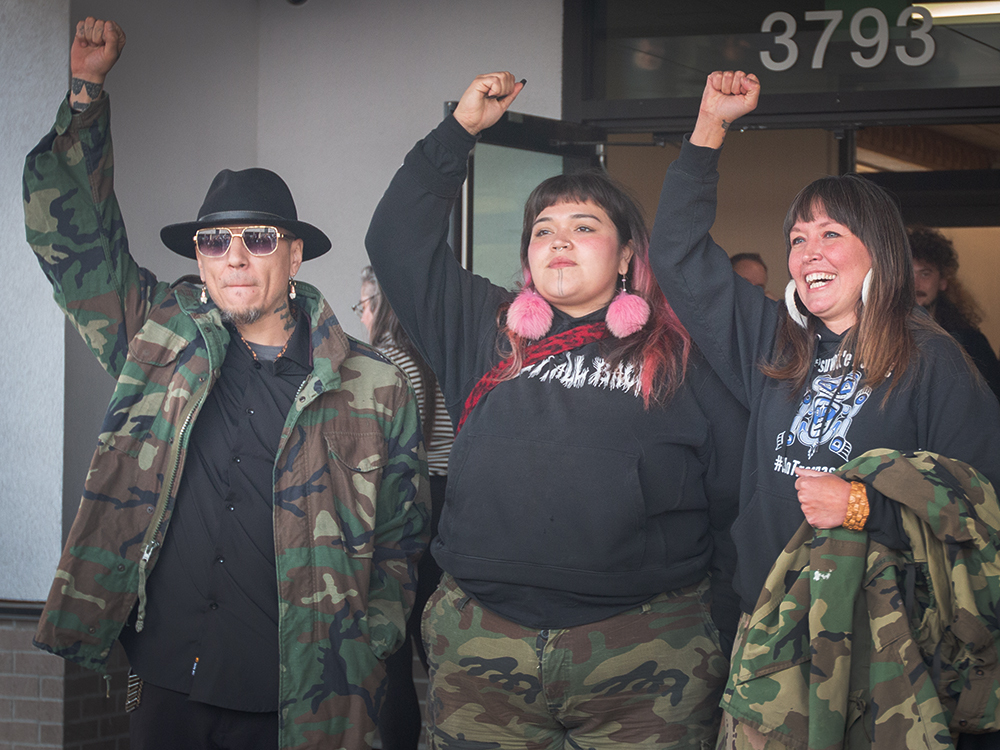

Sleydo’ Molly Wickham, Shaylynn Sampson and Corey Jocko will avoid jail time after B.C. Supreme Court Justice Michael Tammen handed the three suspended sentences, rejecting a Crown submission that they spend time in jail.

The trio were arrested, along with several others, along the Coastal GasLink pipeline route on Nov. 19, 2021.

The sentencing closes a chapter in the years-long conflict over construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline through northern “B.C.,” which sparked solidarity protests that shut down transportation corridors across the country and made international headlines.

Construction on the 670-kilometre gas pipeline was completed in late 2023 after years of opposition by Wet’suwet’en hereditary leaders and several high-profile police actions. Earlier this year, the LNG Canada export terminal in Kitimat began shipping gas transported through the pipeline.

Inside the courtroom, some supporters became emotional as Tammen acknowledged the Wet’suwet’en hereditary leaders’ decades-long fight to affirm the nation’s rights and title — and the “B.C.” and “Canadian” governments’ failure to engage meaningfully in negotiations over the outstanding claims.

He said these broader issues created “unique circumstances” that directly led to the land defenders blocking access to the pipeline route, and he took them into consideration while determining whether they should receive jail time.

“If, by suspending the implementation of the remaining jail sentence in this case, I can advance the goal of reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples even infinitesimally, I should seriously consider it,” Tammen said.

Crown prosecutors had argued that Sleydo’, Sampson and Jocko should receive 30, 25 and 20 days in jail, respectively, plus credit for time spent in custody following their arrests. They also suggested the sentences be reduced further due to police conduct during the arrests, cutting the sentences by roughly half.

But instead of sending the three to jail, Tammen suspended the sentences on the condition that they complete 150 hours of community service work, abide by a court injunction issued to the pipeline company and be on good behaviour.

After the decision, Sleydo’ — a member of the Wet’suwet’en Gidimt’en Clan — thanked the Dini ze’ and Ts’ako ze’ (hereditary chiefs) who have stood up for the nation’s land rights.

“What they did and how hard they fought and the fact that we still have lands and territories … today, that really showed,” she said outside the courthouse.

“It feels really good today to not be going to jail,” Sleydo’ added, to cheers from those gathered.

A series of conflicts

The Coastal GasLink project was approved in 2014 despite long-standing opposition from Wet’suwet’en traditional leadership. The federal and provincial governments have pointed to benefit agreements signed between Coastal GasLink and five of six Wet’suwet’en band councils as evidence of support for the project.

The dispute first boiled over in January 2019, shortly after Coastal GasLink obtained an injunction preventing anyone from blocking access to pipeline access roads and work sites.

Sleydo’ was among those arrested but was not charged.

Further police actions occurred after supporters of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs closed the Morice Forest Service Road, which provides access to the pipeline route, in 2020 and 2021.

In September 2021, pipeline opponents occupied a remote work site where Coastal GasLink was preparing to drill under the Wedzin Kwa (Morice River). The river is a major tributary of the Skeena River and has been the focus of concern over damage to water quality and salmon populations during pipeline construction.

On Nov. 14, 2021, the standoff escalated when Wet’suwet’en hereditary leaders ordered the closure of the Morice Forest Service Road, stranding more than 500 workers at a remote camp, the company said.

Four days later, RCMP enforced Coastal GasLink’s injunction, arresting 14 people at Gidimt’en Camp, 44 kilometres down the Morice road.

The following day, on Nov. 19, 2021, RCMP moved to make arrests at the drill site another 20 kilometres from the camp.

In total, 30 people were arrested over two days and 19 were later charged with criminal contempt of court. While some pleaded guilty, one person, Sabina Dennis, was found not guilty following a trial in November 2023.

In that case, Tammen determined that Dennis had intended to play a peacekeeping role as police officers moved in to make arrests.

Sleydo’ and Sampson, who is from the Gitxsan Nation, were arrested inside a “tiny house” that was located on a work site next to the pipeline route. Jocko, who is Haudenosaunee and from “Ontario,” was arrested the same day in a separate building that had been constructed on the pipeline route.

Trial, appeal and sentencing

They were found guilty following a trial in January 2024. Immediately after the verdict, the court held a hearing into allegations that arresting police officers had breached the Charter rights of the trio.

The hearing revealed that police had set up snipers in the area prior to the arrests and considered sending a police dog to pull people out of the structures in which Sleydo’, Sampson and Jocko were arrested.

The court also heard recordings of RCMP officers making derogatory comments about red face paint worn by Sleydo’ and Sampson. The paint recognized the high number of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in “Canada.”

“I found those comments to be grossly offensive, racist and dehumanizing,” Tammen said on Friday.

He added that the comments amounted to “serious misconduct” and the need to “take tangible steps to attempt to restore respect for the justice system.”

“The need to take action is acute when the offending behaviour by state actors is racist commentary making light of the plight of the many murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls,” he said.

Tammen also found that the time the defendants spent in transit over several days following their arrests was “the harshest possible conditions of confinement.” That confinement included time spent in holding cells at RCMP detachments, hours of “arduous transport” in vans, irregular meals and no amenities.

Finally, the officers should have obtained a warrant prior to entering the structures and making the arrests, Tammen said.

He added that the “dark shadow of the legacy of colonization looms large in the broader backdrop” to the case.

“The territory on which these offences occurred is part of the unceded Wet’suwet’en lands, or yintah,” he said, referring to the Wet’suwet’en word for territory. Tammen referenced the 10-year-long Delgamuukw-Gisday’wa court case that resulted in a ruling that Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan title had never been extinguished.

The case ended with the Supreme Court of Canada encouraging the parties to reach a resolution through negotiation, Tammen said.

“In the intervening 28 years, there has been no resolution,” he said. “A fundamental issue which appears to be unresolved is recognition by both levels of government of the hereditary chiefs as the appropriate individuals to speak on behalf of the Wet’suwet’en as opposed to the band councils.”

Tammen added that despite the fact the hereditary chiefs were the plaintiffs in the Delgamuukw case, some “maintain that they were not consulted appropriately with respect to the project.”

He further pointed out that negotiations that followed the 2020 arrests led to the creation of a memorandum of understanding between the hereditary chiefs and the provincial and federal governments that recognized the role of Wet’suwet’en leadership in governing the yintah and that committed to further negotiations.

“The honour of the Crown was squarely engaged,” he said, adding that both governments “recognized the hereditary chiefs … as the rights and title holders.”

“What is clear is that the MOU has not been meaningfully implemented in the more than five years since its execution,” he said, adding that the failure was “part of the backdrop to the offending behaviour.”

As he concluded his decision, Tammen recognized the “solemnity and dignity” of those who had been involved in the case and attended the “Smithers” courthouse over several years, where heightened security meant supporters were subjected to bag searches and metal detectors as they entered the courtroom.

“With respect to the people before the court and their supporters who have filled this courtroom … the behaviour has been exemplary,” Tammen said. “That is not always the case in these emotional contempt-of-court cases in this province.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

‘NDN Giver’ exhibition showcases the art — and responsibility — of potlatching

From mugs to prints, masks and blankets, a new Bill Reid Gallery display celebrates the ancient Northwest Coast gift-giving tradition