Province commits to ‘new vision for child welfare’ after 11-year-old’s preventable death

The ‘incomprehensible’ and ‘shocking’ abuse case was investigated by the RCY in a new report that shines light on system failures and calls for change

CONTENT WARNING: This story details abuse and neglect in the child “welfare” system that may be distressing or triggering. Please look after your spirit and read with care.

The provincial government is committing to “a new vision for child welfare” after an investigation exposed dozens of failures that led to the preventable death of an 11-year-old First Nations boy in a “Fraser Valley” foster home.

The Representative for Children and Youth (RCY) released a report this week that delves into the story of Colby — whose real name and specific community have been withheld to protect his identity — and the horrific abuse he endured that led to his untimely passing.

The mistreatment of Colby and his eight-year-old sister — which included starvation, beatings and torture — was called “shocking” and “incomprehensible” by a provincial court judge who sentenced their two caregivers to 10 years in prison in 2023.

After the RCY’s report was unveiled on Tuesday morning, “B.C.’s” Minister of Children and Family Development (MCFD) Grace Lore apologized and acknowledged that the system failed.

The province said in a statement that it’s committing to systemic changes and a more collaborative and prevention-based approach to child welfare based on the report’s recommendations.

“The story of Colby and his family could have been different if they had what they needed when they needed it, and for that, I am sorry,” Lore said.

“We are committing today to a new vision for child welfare in this province … A new approach that will take all of government working together, guided by the work of the representative and her team.”

‘This was an innocent young boy’

RCY Jennifer Charlesworth’s new 200-page report “Don’t Look Away” details how when Colby was born in 2009, he was considered a “miracle baby” because he was delivered by emergency c-section and had a twin who did not make it.

A relative recalled in the report that “he was a sweet, sweet baby, but he made me really nervous” because he was so small, quiet and fragile. He had various complex health problems that required regular attention and medication but took on these challenges with “a remarkable, positive spirit.”

Colby loved to play soccer, read comic books and play Minecraft, and his favourite subjects in school were science and math. He loved learning about his First Nations culture and took part in an honouring ceremony in his community when he was nine-years-old.

Colby also expressed love and care for everyone around him, and liked to give each of his classmates a hug when he arrived at school and often held his little sister’s hand in the hallway. He was one of five children.

However, Colby did not receive that same affection in return from the adults that were trusted to protect him.

Facing a turbulent home life, Colby was removed from his mother’s care in 2019 and placed in the home of her cousin and her partner in the “Fraser Valley.” While he was in their custody, he was isolated from the rest of his family and regularly absent for school and medical appointments, the report says.

Colby died of a head injury in 2021 after being severely beaten, and investigators found shocking video evidence of an inhuman level of abuse that occurred at the hands of these extended family caregivers, who locked Colby and his sister in a dark closet, subjected them to severe physical violence, tortured and starved them.

Charlesworth said the RCY identified more than 40 points in Colby’s life where opportunities to intervene were missed.

“This was an innocent young boy, who should have had no worries except perhaps whether or not he scored a goal in a soccer game, or getting to the next level in a video game,” she said.

“He should have been able to be happy, carefree. Instead, he became the center of headlines, homicide detectives … and debates in the legislature. His bright smile was eclipsed by a dark, dark chapter in B.C.’s child welfare history.”

The report says that MCFD and other agencies did not adequately follow up and a social worker responsible for Colby’s wellbeing did not see him for seven months before his death.

The report found “a failure to adhere to legislation, policy and practice requirements designed to protect the safety and rights of children including missed criminal record checks.”

There were also “inadequate assessment and follow-up to reports of family violence, flawed decision-making regarding placements for the boy and his siblings and confusion over roles and accountability between the ministry and Nation that the boy belonged to.”

Thousands of reports of death and injuries: RCY

Charlesworth ultimately concluded that a transformation of the current system is required and it must be through a “whole of government approach” to child welfare.

“It would be too easy to point the finger at a worker, or the caregivers or MCFD and blame them for this tragic outcome. But what we see when we look at the totality of this boy’s story are multiple missed opportunities by many people and agencies, not just a single person, or a single ministry,” said Charlesworth in a statement.

“In spending almost a year looking very closely at what happened to Colby and his family and examining the systems of care more broadly, we are saying unequivocally that significant change must happen.”

In 2023/24, the RCY received 6,437 reports of deaths and injuries impacting young people in provincial “care” or receiving related services and programs, according to the office, “with close to 3,000 of these meeting the criteria for critical injuries and deaths that are within RCY’s mandate for reviews and investigations.”

“Every month, the RCY receives hundreds of reports of critical injuries and deaths of young people in care or receiving government services,” Charlesworth said.

The RCY’s report delves into the stories of 14 more children who, like Colby, died or experienced catastrophic injuries while in MCFD custody. These harms disproportionately affect Indigenous children, who make up 70 per cent of the children in provincial “care” despite making up less than 10 per cent of the entire child and Youth population.

“Some have described the current B.C. child welfare system as the modern-day residential school,” the report says.

“When you examine Colby’s story — and those of other Indigenous children who have been harmed by the system — it’s difficult to argue with that description.”

An ‘archaic’ and ‘colonial’ child welfare system

Weaving in the stories of affected children, RCY makes a series of short and long-term recommendations in five key areas: enhancing child wellbeing, addressing violence, supporting families and “kinship carers,” enhancing accountability and supporting jurisdiction.

Minister Lore said MCFD is in the process of hiring an Indigenous child welfare director, and looking at creating an Indigenous-led body that can support First Nations governments with taking on jurisdiction.

“There have been many years with Indigenous children overrepresented in our system, and we need to do everything together, working together with Nations and community, to support the safety and wellbeing of kids as we pursue and work together on jurisdiction,” she said.

Charlesworth said the onus must fall not only on MCFD but the entire system to ensure that changes are made and the child welfare system — which was called “archaic” and “colonial” by leaders attending the report release — does not keep failing.

She described the current momentum as a “collective lift” that she said has involved consulting with thousands of people who are all eager to make and see change. She said this included hours-long interviews with family members of Colby.

“It’s simply not sustainable with the system that we’ve got, and it’s not working with kids,” said Charlesworth. “So no better time than right now to reimagine where we’re going.”

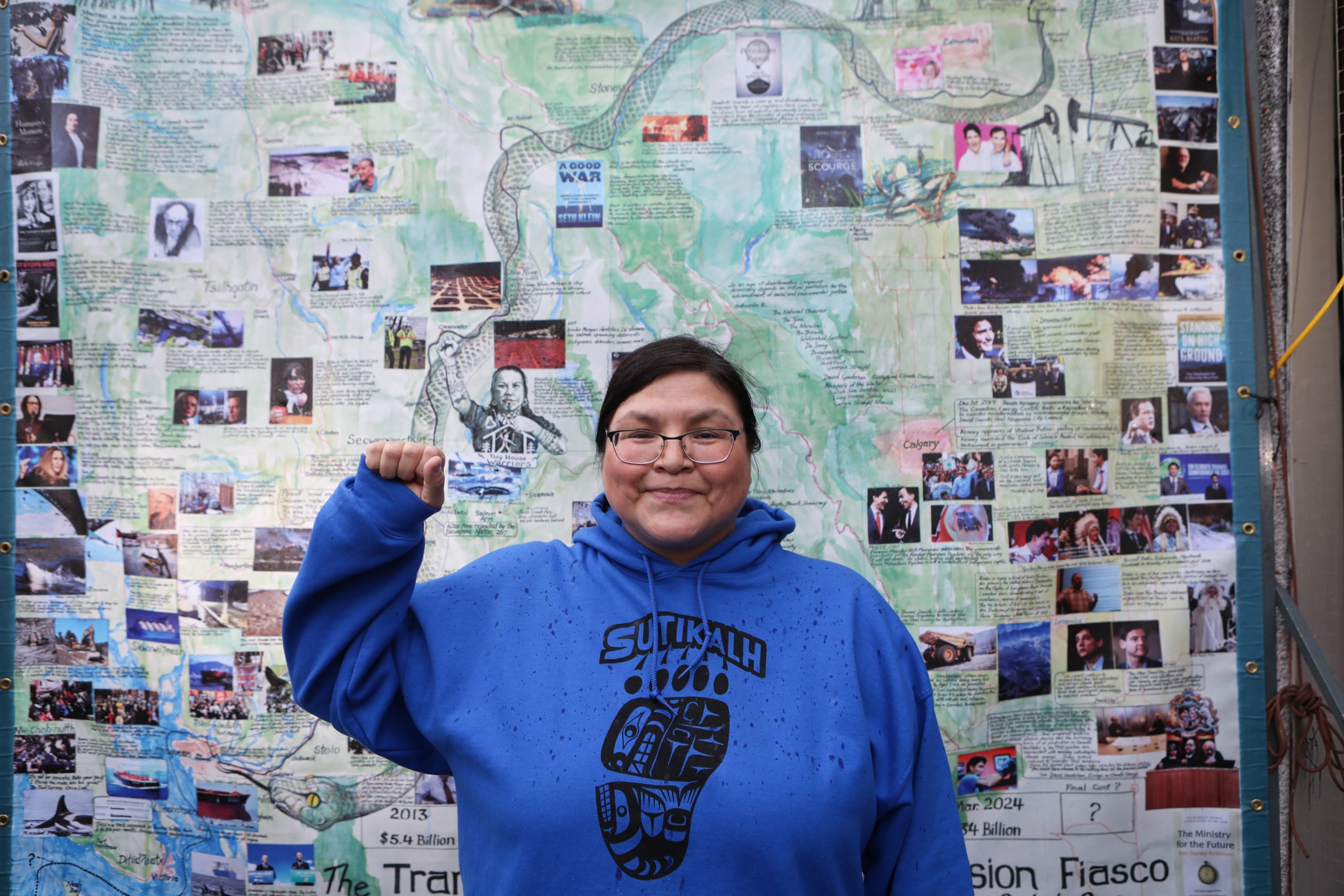

Indigenous groups who have advocated for change in the child welfare system — the First Nations Leadership Council and Our Children Our Way Society — welcomed the release of the report.

“It is unacceptable that these horrific situations have continued to occur in foster homes in B.C. It must stop,” said Cheryl Casimer of the First Nations Summit, in a statement.

“We need to see real and tangible systemic change that includes collaborative and culturally appropriate approaches, as well as strengthened accountability measures, to prevent similar deaths from occurring in future.”

Mary Teegee, the chair of the Our Children Our Way Society, said the provincial government’s commitment to work collaboratively on child welfare is “unprecedented.”

“The Our Children Our Way Society stands ready to work together to achieve the results our children need,” she said, “to hold the government accountable for fulfilling this commitment, and to hold ourselves accountable for keeping our children safe, loved, and well during this time of system transformation.”

‘Time will tell if it’s good work’

Following presentations about the report and actions that will be taken, Willie Charlie of Sts’ailes Nation said he appreciates the effort and intent, but encouraged leaders not to get ahead of themselves.

“There are lots of good reports sitting on the shelf, good recommendations that never get implemented,” he said.

“So we’ll see, time will tell if it’s good work.”

Charlie also spoke about the Coast Salish grief cycle and expressed concern about Colby’s spirit not being allowed to rest.

“He can’t fully go to the Spirit World until we release him,” he said. “And every time we cry for him, every time we grieve for him, every time we mourn for him, every time we get angry about what has happened to him, we’re keeping him here.”

Colby’s family continues to be impacted following his death. His mother passed away 20 months later, and two of her children were placed in an off-reserve group home in December of 2023 and are disconnected from their other siblings, the report says.

Only one of Colby’s siblings is living with a family member “and there remains a lack of family connection for the children despite requests from several family members.”

“RCY has since received a reportable circumstance concerning mistreatment of one of the children by a staff member, witnessed by the other child,” the report says.

“Family members have expressed significant concerns about the well-being of the children in their current placements and continued lack of belonging and connection.”

The report notes that MCFD is involved and there’s hope that some of the children will be able to live together in the future.

Lore acknowledged that people have concerns about whether change will actually happen, given that “this is not the first report. This is not the first story or stories of children that we need to hold close in this work.”

“So we are committed to a new vision to starting this work now, and into the fall, with senior public officials who can get this work going,” she said.

“And answering the call for a government-wide action plan, for an outcome framework, so that we know what steps we need to take, and then are able to measure the impact we have, so that we know that the work we’re doing is improving the lives of kids.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

Children’s book tells residential ‘school’ story from a kid’s perspective

‘Shirley: An Indian Residential School Story’ — released today — was written by Joanne Robertson with, and about, Elder Shirley (Fletcher) Horn