St. Augustine’s survivor hopes for closure after evidence of 81 unmarked graves released

50 years after the residential ‘school’ closed, shíshálh Nation announces evidence of many burial sites. A Tla’amin Elder wonders how many more children died

Content warning: This article contains details about the deaths of children at residential “schools.” Please read with care for your spirit.

An Elder from Tla’amin Nation hopes more children who died at a residential “school” in “Sechelt” can be identified, so their communities can find closure and healing.

Yahum (John Louie) — a survivor of the former St. Augustine’s Indian Residential School on the “Sunshine Coast” — spoke with a shíshálh Nation research team to help identify areas to scan around the institution’s grounds.

It was part of a years-long investigation into children’s deaths there, which culminated in shíshálh Nation announcing in August that archeologists had found evidence for 41 unmarked and shallow graves — in addition to 40 it identified in 2023.

Yahum said he believes the number of deaths at the institution is far higher than 81, however.

The Elder attended St. Augustine’s for eight years, from ages five to 13, and wonders how families and communities can begin to find closure from the horrors that happened there.

In the 50 years since the institution closed in 1975, he said he has been haunted by traumatic memories of a furnace room at St. Augustine’s.

“They found those ones that are buried,” Yahum told IndigiNews. “But there were… little babies that were thrown into the furnaces.

“How many of those ones? Even the parents didn’t even know about them.”

Finding ‘every child that was disappeared‘

Yalxwemult (Lenora Joe), shíshálh Nation’s lhe hiwus (Chief), said her nation is deeply saddened by the evidence of dozens of unmarked graves. But shíshálh members aren’t surprised.

“We have always believed our Elders,” Yalxwemult stated in an Aug. 15 news release.

“This wasn’t a school — it wasn’t a choice, and the children who attended were stolen.”

The nation’s research included interviews with survivors, historic documents, and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) scans by archaeologists from askîhk Research Services.

The technology has been used by forensic investigators for decades, according to the Indigenous-owned company’s website.

Pushed by hand over the surface, GPR scanners send radio waves into the earth — creating an image of underground layers to help see “what is under the ground without digging.”

GPR cannot “explicitly” find human remains, the company notes, but “the images can be used to identify where disturbance has occurred.”

To ensure findings are as accurate as possible, askîhk’s website states, “We use multiple lines of evidence, such as survivor truths.”

Archeology researcher Micaela Champagne, the company’s CEO and co-founder, acknowledged that her ground-penetrating radar results can bring up trauma and be difficult to hear.

So askîhk’s intention is to complete the GPR surveys in a trauma-informed way, she said, so there is no uncertainty about where a child may be buried.

“We will continue to search for areas identified by survivors, by knowledge keepers, by families,” Champagne said.

“We want to make sure that every child that was disappeared is found.”

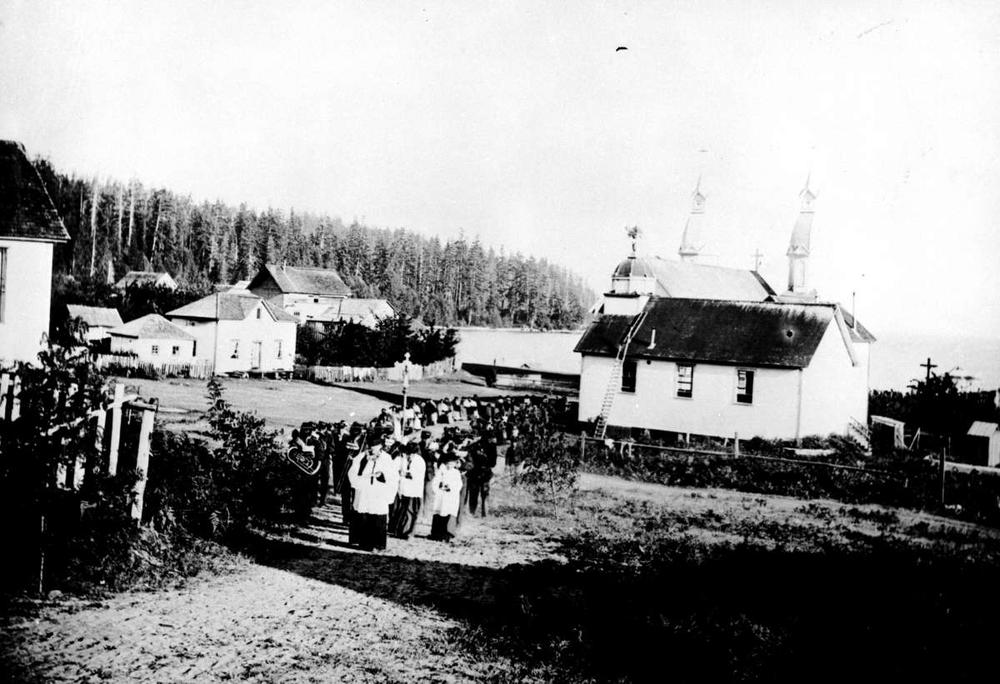

Canada and the Catholic Church ran St. Augustine’s residential “school” — also known as Sechelt Indian Boarding School and Sechelt Industrial School — from 1904 until it burned down in 1917.

It was rebuilt five years later, operating until 1975 when it was destroyed by arson, according to National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation records.

The Manitoba-based centre’s website lists 12 names of children confirmed to have died at St. Augustine’s.

“When I think about the finding of the young ones there, I often think about how many times — how many of them?” Yahum said in an interview.

“Did they have the opportunity to say anything? No, they didn’t. They were punished just because of who they were.”

Punished for what survivor saw in furnace room

Yahum shares similar feelings to lhe hiwus Yalxwemult; he said he’s always known about the deaths.

As he helped archeologists identify places to scan, Yahum asked the researchers “if they had checked over there, and there,” pointing out what he remembered to be fellow students’ burial places.

“Those of us who went to the ‘schools’ at that time knew about them,” he said.

Yahum said he often thinks about fellow students who died at the institution, and believes the number of deaths are far higher than officially documented.

Yahum told IndigiNews he witnessed what he believes was a baby being thrown inside a furnace in the “school” during his time there.

His account echoes what many survivors at other institutions across the country also say they witnessed.

Similar accounts were the subject of the Oscar-nominated documentary Sugarcane, which investigated stories of babies being fathered by priests at the St. Joseph’s Mission in Williams Lake and then thrown into an incinerator at the facility.

Survivors of the Alberni Indian Residential School also recalled babies being burned in an incinerator.

For many years, Yahum and other survivors say they were afraid to speak about what they had seen — citing concerns about being punished or disbelieved.

According to Yahum, the incident happened when he was roughly seven years old. One Saturday, he and other children were kicking a ball in a field when his shoe split open.

One of the Catholic lay brothers — a man who took religious vows but was not a priest — told him to find someone in the “school’s” furnace room to repair his shoe.

“There was a long staircase that went down to the base of the furnace room,” Yahum recalled. “And right across from the door was the huge furnace, and the furnace door was open. There were two nuns plus a priest.”

Yahum recounted seeing both nuns outside the furnace “carrying something in white” wrapping — as the priest conducted what appeared to him to be a Catholic ritual for the dead.

“When he saw me, he yelled at me — told me to get out of there,” Yahum said.

“So I ran out, and then I went and hid behind the school on the side of the building, scared.”

Roughly 20 minutes later, he said, someone called his name to come out from hiding.

“I got punished right in front of everybody on that field,” he said, struck with a strap 10 times on each hand.

The lay brother who’d sent him to the furnace room “wouldn’t even say anything.”

But the punishments didn’t end there; for two weeks, he recalled being denied supper.

Decades later, Yahum is a long-time advocate for cultural healing and wellness. He currently supports an ʔayʔaǰuθəm (ayajuthem) language class at the high school in “Powell River.”

Though shíshálh Nation said some survivors were uncomfortable returning to the former site of St. Augustine’s to assist researchers, Yahum was willing to go — seeing it as part of his healing process.

Secrecy and fear carried ‘back to their communities‘

Being disciplined for witnessing something traumatic has made it “very hard to tell a story like that,” the Elder explained.

“And sadly, there’s a lot of our people that are like that. They carry it and they don’t want to share it.”

Like many residential “school” survivors, Yahum remembers being punished simply for trying to talk with his own siblings there, because staff forcibly segregated brothers and sisters.

“We did try to, but we had to talk to each other in a kind of secrecy and of fear that we might get punished,” he said. “So you learn pretty quickly.

“A lot of our people carried that back to their communities.”

Separated from their parents there, the kids didn’t receive the teachings of their cultures, such as love, respect and honour.

Without their families around “to guide you and teach you,” he said, instead the institution used “screaming, yelling, punishment, line up, ‘do this, do that’ — really military style,” he recounted.

“So you learned to keep quiet and do what you’re told.”

‘We take our last walk with our loved ones’

Many St. Augustine’s survivors have shared accounts similar to Yahum’s, shíshálh Nation noted.

Some remembered children being led by staff into a nearby forest in the middle of the night, never to return — and those who witnessed it being punished for asking questions about what they saw.

“Survivors have carried these horrors, and the disappearances of their siblings, cousins, and peers, in addition to their own experiences,” Yalxwemult said.

In 2018, Yahum took part in a healing ceremony with community members from Homalco, Klahoose, and Tla’amin Nations, calling home the spirits of lost children from the “school.”

At the time, there was a large survivors’ walk in “Vancouver,” but many Tla’amin members couldn’t attend. Nonetheless they wanted to do something similar in t̓išosəm, a Tla’amin village.

Yahum suggested bringing cedar to the local residential “school” memorial, and to ceremonially brush the area.

“Then we’ll bring the spirits of those individuals that came from here,” he said.

They carried the cedar to the local graveyard, walking up from a church in t̓išosəm village “like we do in our funeral services,” he recalled.

“We take our last walk with our loved ones, so that they’ll find some peace at home here.”

Yahum said the ceremony was “really emotional,” because even though they didn’t know all the names of children who died at the “school,” the community holds a deep connection with them.

“Those were kids that slept beside you, ate beside you, we played with them,” he said. “Some of them didn’t return home, so their spirits got stuck there.

“That’s why we went and did that coming-home ceremony — hopefully to at least release them.”

At the same time, he recalled, they also wanted to show gratitude to the shíshálh people “for looking after our loved ones who never made it back home,” he said.

“It wasn’t their fault that they were stuck in [shíshálh] homeland.”

For the children who never got to go home because of what had happened to them, Yahum is glad the truth is finally coming to light about what happened.

“We need to get the government to be accountable for their part in that, and the church,” he said.

According to shíshálh Nation, children from 53 other First Nations attended the institution. Many were from across the province, but some came from as far away as “Saskatchewan.”

“There are survivors from other communities who don’t want to come to Sechelt because of their trauma from St. Augustine’s,” Yalxwemult said. “They have bad feelings towards our community.

“We understand because this trauma was done to us, and this is our home. We want to heal together.”

After the nation released its findings, the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre said it was “deeply saddened by the confirmation of these truths,” according to an Aug. 29 statement.

“We recognize the profound grief that each new finding brings,” the University of B.C.-based centre said.

“Locating these ancestors is an important step toward ensuring they are properly cared for in ways that honour their dignity and the ceremonial responsibilities of their people.”

‘We always had enough proof to know’

Yahum said he doesn’t know if there will ever be an opportunity to find out who every buried child was, or where they came from.

But for their families’ and communities’ sake, he hopes they will one day all be identified.

He said many survivors have until now been afraid to speak publicly about “things that we’ve seen, what we heard, that we were never allowed to talk about.”

“If we did, we would have got punished, and they… would be telling other people we are making up stories.”

By sharing the heavy news of shíshálh Nation’s GPR findings, Yalxwemult explained, “we want to protect our people and our community, and the other nations whose children are directly connected to this.”

On Sept. 17, shíshálh Nation members attended a graduation ceremony for survivors of St. Augustine’s residential and day “schools,” hosted by the nation, Sunshine Coast School District, and Syiyaya Reconciliation Movement.

The event honoured Elders, many who came dressed in traditional blankets, gowns, and woven cedar hats.

Attendees drummed, sang, and recognized survivors — as well as those who did not survive St Augustine’s.

In a statement, Yalxwemult said her community “didn’t need” the ground-penetrating radar results to prove the trauma they’d experienced.

“We always had enough proof to know,” she said. “We are not taking ownership of the trauma because that was done to us.

“But we are taking ownership of our healing, our message, and our future.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

‘This is the vision’: Inside Nlaka’pamux Nation’s quest to build ‘B.C.’s’ first major solar project

As the province fast-tracks development, the Southern Interior tribal council has lessons to share on how to build for the future

-

Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Youth connect to their lands — and relatives — with annual Rez Ride

The Menmen tl’a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh mountain bike team pedals through ancestral villages — guided by Elders, culture and community spirit