Púti kwu aláʔ (we are still here): Sinixt people journey ancestral waters after court victory

Decades after displacement and attempted erasure, Sinixt people and supporters crossed the colonial border to canoe through their lands in ‘British Columbia’

During a week-long canoe journey through their ancestral waterways, a group of Sinixt people burned a letter that falsely declared their people “extinct” in 1956 — rejecting a longstanding attempt to erase them from their homelands.

The ceremony was one of many stops on the journey, which occurred between June 12 and 19, where Sinixt people living in the “U.S.,” joined by supporters from other nations and communities, crossed over the colonial border to reconnect with their territory in “British Columbia.”

Remey LaCombe, a Sinixt archaeologist whose great grandfather was pushed out of northern Sinixt homelands in the early 1900s, joined the canoe journey with his wife and three children.

LaCombe said being on the water was “overwhelming at points,” largely because of the intense connection he felt to his ancestors.

“I would get emotional to think…200 years ago, 300 years ago, there was another Sinixt person who was paddling and going over these same waves, in this same spot, in this same type of canoe,” he said. “And I get to have that connection with them, through history, through time.”

The sn̓ʕaýckst place of the bull trout (“Arrow Lakes”) and a northern section of sn̓x̌ʷn̓tkʷítkʷ swift river (the “Columbia River”) are a part of about 80 per cent of Sinixt territory that has been kept out of the reach of many Sinixt people for more than a century.

The influx of early mining settlements and boomtowns forced their ancestors south of the border, often by violent means. Miners also brought a second wave of smallpox into the territory. The waterways, which served as highways for Sinixt canoes, were heavily dammed. This, combined with the implementation of the Canada-U.S. border, constrained Sinixt movement through the territory.

Kelly Watt, who was the canoe bowman during the paddle, said his uncle Robert Watt was one Sinixt person who tried to live within the northern part of the territory as caretaker of their burial grounds at “Vallican” beginning in the early 1990s. He was later deported by Canadian immigration services.

“It never made sense to me why we couldn’t cross [the border], even though we were always from that part,” Watt said, adding that the canoe journey and corresponding ceremonies made him feel like he was “finally catching up on the northern side.”

Canada’s reserve system was another key factor in the displacement of the Sinixt.

“When they set up the Oatscott reserve…it was never going to be sustainable; it was never going to work [for us],” said Shelly Boyd, one of the canoe journey organizers, who added that the small, inhospitable area where Canada corralled the Sinixt people in 1902 was part of a deliberate plan to extinguish her people.

Annie Joseph was the last “legally recognized” Sinixt person living at the Oatscott reserve, near “Burton, B.C.” Shortly after she passed away in 1953, the federal government didn’t hesitate to declare the Sinixt people extinct, despite hundreds of Sinixt still living elsewhere.

“We are satisfied that this band has become extinct,” reads the 1956 letter by Indian Commissioner W. S. Arneil, which goes on to render ownership of Oatscott to the province.

On June 14, a copy of the letter was passed around the circle of about 25 canoe pullers and journey support crew standing across from the reserve, who then burned it in a fire on the lakeshore.

As the declaration letter quickly turned to ashes, each member of the group enjoyed a handful of ancestral foods including salmon, serviceberry, camas and bitterroot.

“Always remember that this food that you eat tonight is the same food, the same tastes, that our people ate,” said Boyd.

“When we were here before, there was such an abundance of salmon…My tupia (great grandmother) said that they could walk across the lake on the backs of the salmon.”

Like the Sinixt who came to paddle, the salmon have also returned home — for the first time in over half a century.

“The first salmon in probably 65 years came up above [Hugh] Keenleyside Dam this year,” Boyd said.

These returning Chinook were likely those released into sn̓x̌ʷn̓tkʷítkʷ swift river by Sinixt and other Colville Tribes in 2019.

“This is a new day for everybody,” said Boyd.

‘Coming here is bittersweet’

The canoe journey began two days after a large gathering in “Nelson, B.C.,” on June 10 where around 100 Sinixt people came to publicly celebrate a 2021 Supreme Court victory, which recognized that the Sinixt have inherent rights to hunt and harvest on their homelands in “Canada.”

It was 2010 when Sinixt ceremonial hunter Richard Desautel was arrested for hunting an elk on his people’s territory north of the border. He took the case to court, and ten years later, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in favour of the Sinixt.

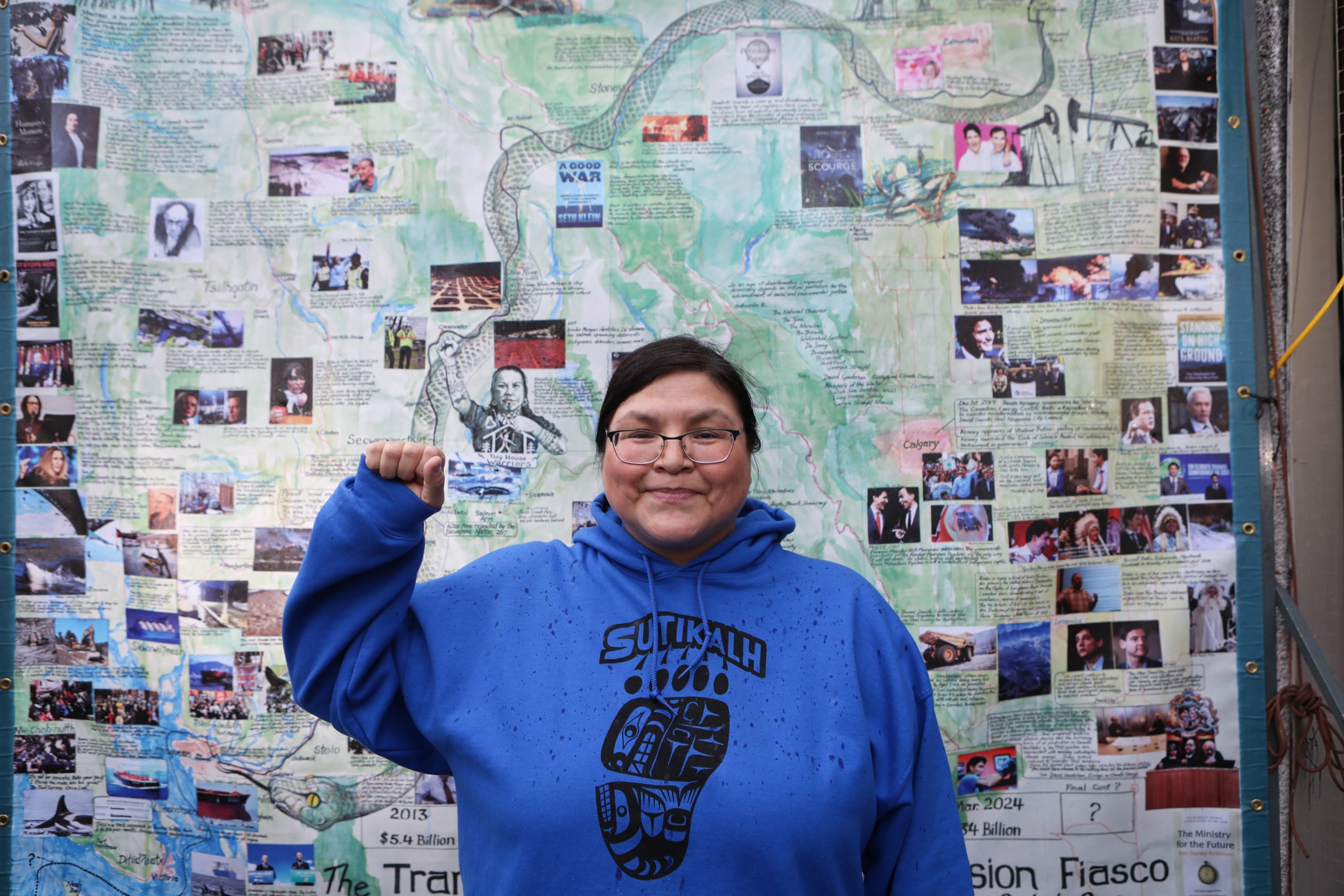

At the June 10 celebration, 300 copies of the extinction letter wrapped in cedar leaves were also burned by those in attendance. Sinixt musician Tony Louie, who performed at that event and also was part of the canoe journey, said this work has been long in the making.

“There’ve been a lot of generations before us that paved the way and sacrificed a lot,” he said, adding that many of them passed away before seeing this day.

“[They] didn’t get to see it but they fought for us and our future children to be able to do this.”

LaCombe’s grandfather, Michael Paul, was one of the many Sinixt people who fought to preserve their way of life, both working to keep their language alive and bringing his children back to northern Sinixt territory.

“My grandfather was working to try to achieve that goal [of reinstating our presence here],” said LaCombe, adding that legacy has inspired his own path.

“As a Sinixt person, I spent my entire life knowing I was going to go up and over the border, and I was going to do as much as I possibly can to bring us back.”

Fiona Fitzpatrick, an 18-year-old Sinixt youth who also joined the paddle with her father Aaron, said being back on the land of her ancestors felt like “walking in the footsteps of those that came before.”

Fiona grew up picking huckleberries with her grandmothers, listening to stories and learning about what it means to be Sinixt.

During the summers, she continues to pick berries with her father, whose berry basket has been used in the family for over four generations. Woven with bear grass in the traditional criss-cross pattern at least 125 years ago, it is one of the oldest Sinixt berry baskets in use today, said Aaron.

“Coming here is bittersweet,” said Fiona, “because neither of [my grandmothers] got to see it. But it also makes it more special because I know they would want us to be here.”

Pulling through sn̓ʕaýckst place of the bull trout and a northern section of sn̓x̌ʷn̓tkʷítkʷ swift river in a hand-carved, ancient cedar tree canoe was profound, she added.

“You think about the age of the cedar and how much that cedar has seen in 600 years. Six hundred years ago, Columbus had just touched down, so this tree essentially was born right as westerners were making first contact with Indigenous people in the Americas,” she said. “This tree has witnessed all of that, so for it to also witness the return of our people is pretty cool.”

Sinixt paddler Donovan Timentwa said his great-great grandparents spent a lot of time in the northern part of Sinixt territory, and his grandmother was one of those Sinixt people who was “forced down” below the border.

Seeing the Sinixt win their court case and to now be back in the northern part of the territory has provided a sense of healing, Timentwa said.

“It’s like one of those happy cries, you know? Meaningful is an understatement. Before the court case, I felt very overlooked.”

The case has helped reaffirm that “púti kwu aláʔ” we are still here, he said.

Yet while the Sinixt are still here, so are the ongoing realities of colonialism, such as continued difficulties crossing the border and generational trauma.

“The genocidal effects are still echoing through,” said Louie. “It’s kind of this rabbit hole of disconnect after disconnect from your own culture and your own identity.”

Louie says the colonial policies imposed on the Sinixt and other Indigenous people have infiltrated right down to the family level, making it hard to come together as a strong people.

But he is hopeful about initiatives like the canoe journey that help Sinixt people reconnect with their ancestral territory.

“We have our homelands to finally express who the hell we want to be,” he said. “This traditional tǝmxʷúlaʔxʷ — this traditional land — that’s where you start. And where it goes from here, that’s beyond me. I’m just one of the many moving pieces.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

Children’s book tells residential ‘school’ story from a kid’s perspective

‘Shirley: An Indian Residential School Story’ — released today — was written by Joanne Robertson with, and about, Elder Shirley (Fletcher) Horn