Stickgames, songs and sobriety: a secwepemc mother’s message of hope

‘It was a good time to share in some love, share in some traditional foods, share in our tradition, and share our hearts,’ says Vi Manuel who was uplifted by her community last week

Stickgames, songs and sobriety are a part of Secwépemc mother Vi Manuel’s story of hope.

It’s been 30 years since Manuel made the first of many decisions to create a new life of sobriety, she shares with a large crowd gathered in the large Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc powwow arbour on July 7.

When the people of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc hosted fire evacuees who went to seek refuge after the Village of Lytton and surrounding areas evacuated to flee Lytton Creek wildfires, they were greeted and continued to be warmly hosted by the community.

Manuel, who was uplifted at one of the day’s events, says she’s proud of her community.

“We’re practicing our ways again— practicing hosting, practicing feeding the people, practicing praying for the 215 spirits, and praying alongside others also going through this,” she says.

“I wanted to do it in a sense where I gave a chance for us to sing freely, to sing in a way where we’re not in mourning.”

Coming together like this is the Secwépemc way, she adds.

“I just wanted to send the message out that we’re here to love you, we’re here to look after you, and that helps us at the same time. It encompasses us, we’re all inclusive of one another, and we will be there for one another for time immemorial,” she shares.

‘Our children are only lent to us’

Standing at the mic in front of over 150 people, including fire evacuees welcomed into the celebration, Manuel says it was her responsibility to change the direction of her family. She spoke about how residential “schools” negatively impacted her family for generations.

“My parents didn’t get a chance to raise me, my grandparents didn’t get to raise them, and my great grandparents didn’t get to raise their children, because of the residential school,” she says.

People ate and shared gifts, while singing and drumming continued, sounds vibrating throughout the arbour and lifting up into the starry night sky.

Manuel spoke about the importance of becoming sober.

“My family had been traumatized for generations, and I was the first generation that actually had the gift of being able to raise my child,” says Manuel sitting on one of the bleachers of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc powwow arbour.

With this gift came great responsibility, she explains.

Children are “only lent to us,” she says, a teaching she came to understand after 34 hours of labour. Her daughter, Whitney Alphonse, has given her a gift of knowing what it means to nurture the passion of the youth, she explains.

“I was going to one day face the Creator and answer about how I looked after his child, or our child, before she came back,” Manuel says.

She remembers taking her daughter, who was ten years-old at the time, to an All Natives Basketball Tournament.

“What she ended up witnessing were educated academic athletes, and it inspired her,” she says.

Her daughter loved watching Indigenous women, not only be academic athletes, but being strong, and “standing in their own power,” Manuel says.

“She had these dreams, and I knew that it was my responsibility to help her make these dreams come true,” she says. “That’s what helped me with my parenting, and what helped change our direction.”

Manuel began to follow the sounds of drums wherever they could be heard, and attended stickgames, powwows, and ceremonies. It was the healing vibration of the music that kept her on her path, as well as honouring the life ceremony of her daughter, she explains.

Alphonse, now a mother of three, a University student, and successful business owner, says her mother has given her the greatest gift of her life.

“I always watched my Mom do everything she could for me — she would never take no for an answer if I needed anything — she is the type of mother that would move the stars around the galaxy for me,” says Alphonse who will soon graduate and pursue her career in Indigenous Archeology.

Now Manuel says it’s time for Alphonse to continue her work.

“I told [Whitney]…now it’s your turn to decolonize and carry it on,” says Manuel.

Alphonse says she intends to do exactly that, and since her mother made the brave choice to heal, she will continue the work.

“Because of that intergenerational healing she’s decided to take the step forward and do that healing herself, and transferred onto me and now her grandkids. It will always be reflected in her legacy,” says Alphonse.

Healing Power of Song

It’s drumming, singing, and sharing in old ways that keep her grounded in who she is, Manuel says.

She stood in the centre of the arbour while drummers came to honour her journey and new life and path she created for so many others.

“I was so grateful, because those young men and women have pulled me through the toughest times of my life. Singing songs and prayers literally pulls my spirit back into my body when I need to ground myself. I’m super grateful for that, super grateful for their talents,” she shares.

In these times of grief, mourning, and facing truths that are hard on the spirit Manuel shares a token of advice, and an offer of love to those who may be struggling.

“Go find a place where they are singing,” she says, as the vibrations of the drums vibrate the air around her.

“Go let the prayers surround you, let yourself feel the love, let yourself talk to the ancestors through the song, let your feet touch the grass, release and let the Creator take care of you.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

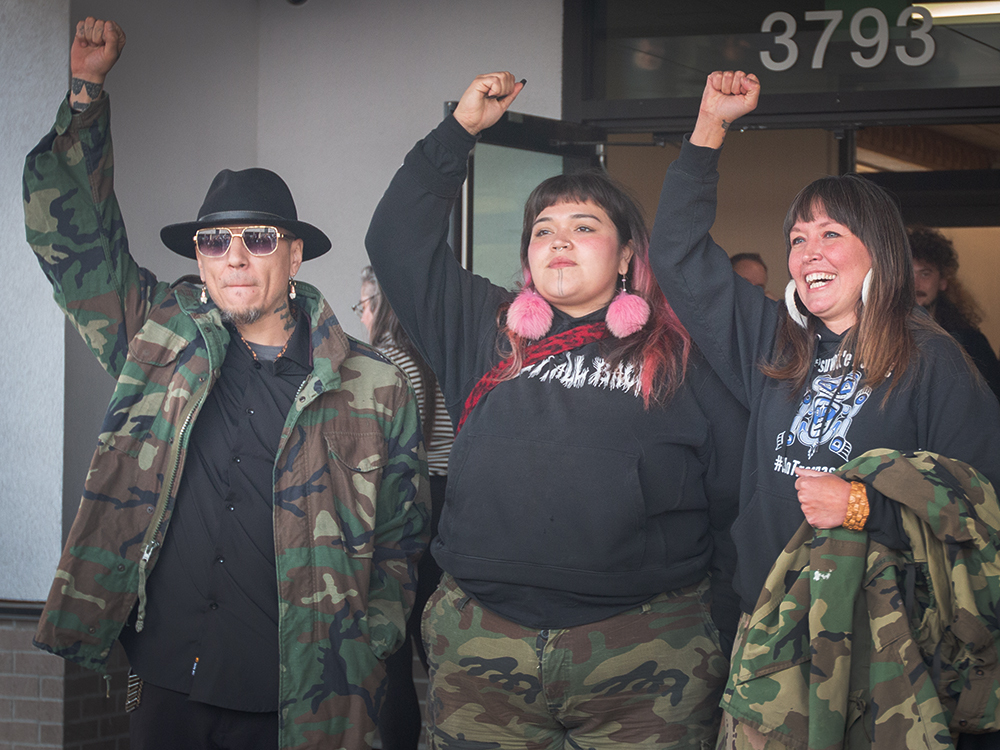

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

-

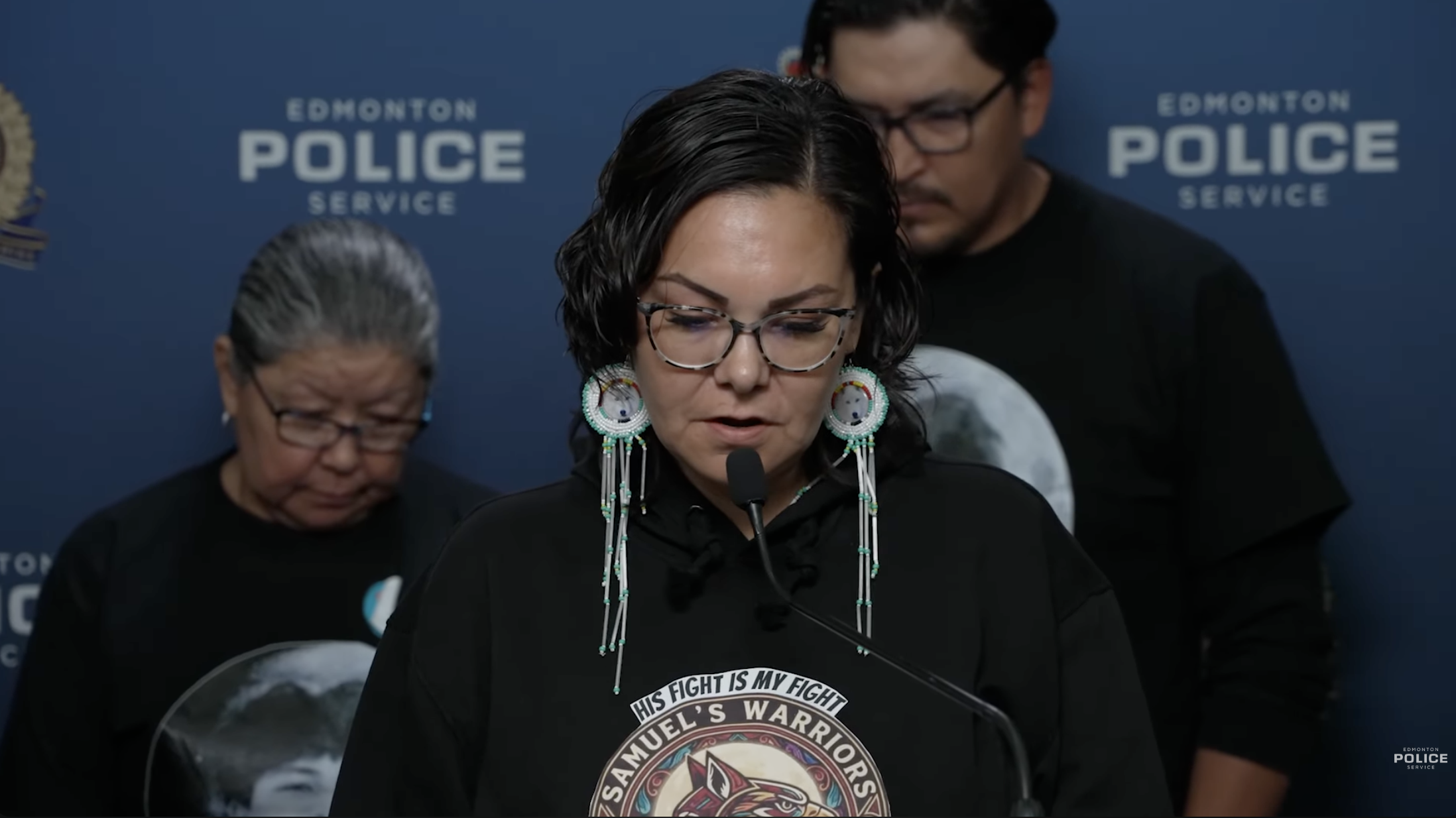

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death