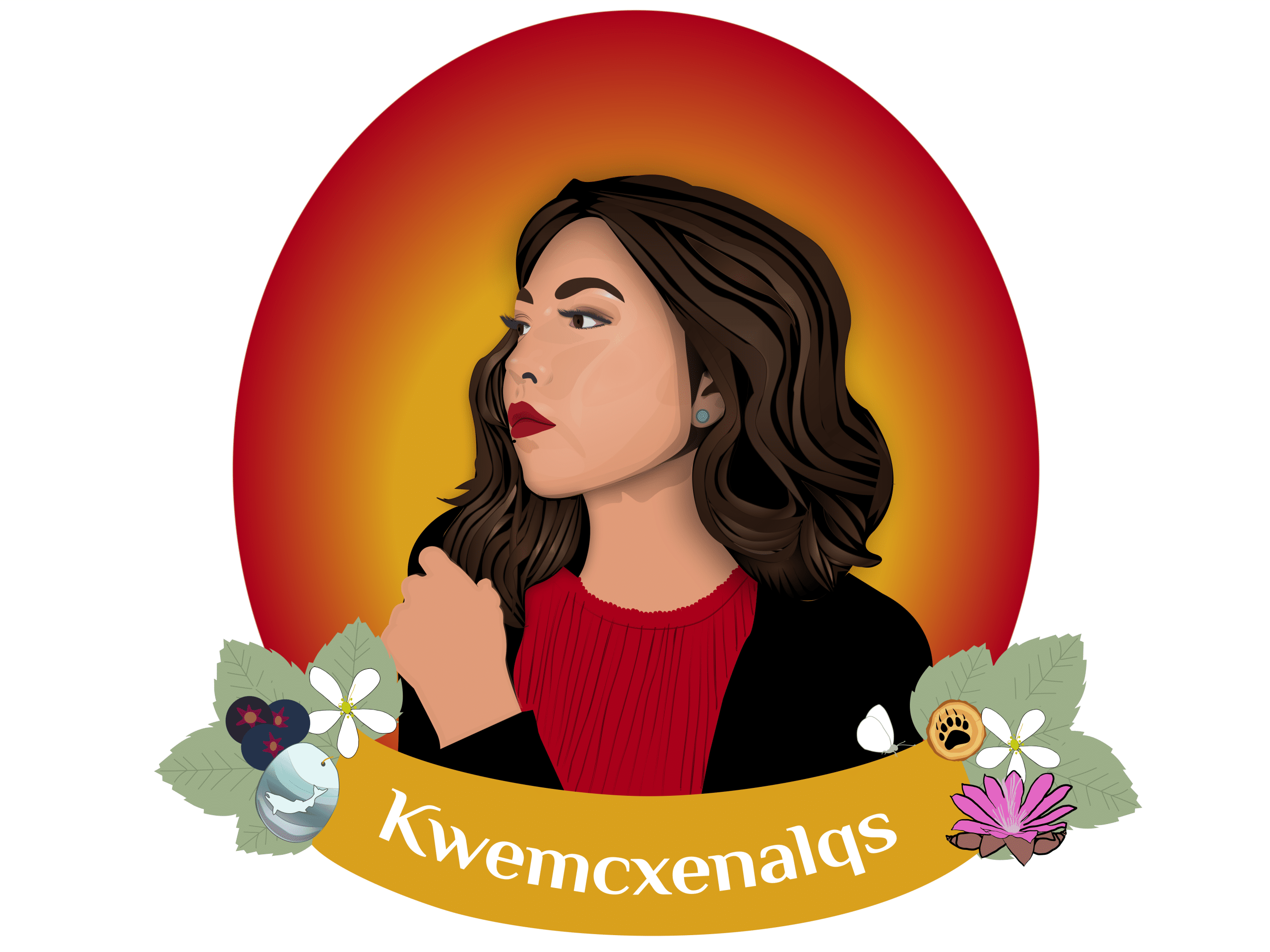

Their name was Kwemcxenalqs

A beloved relation who embodied her name — a sqilx’w young person remembered for her strength

Editor’s note: This story was written in consultation with Juanita Lindley and family with respect for grieving protocols. In accordance with this, we respectfully ask other media to refrain from extracting from this story in any way. IndigiNews cites UNDRIP article 31 which upholds our right to control and protect our stories and histories.

The family has released a separate statement directed at police and media here — they ask you to please not publish any of it, but instead use it to inform your practices.

“She’s just behind the house, sitting under the tree.”

Susan Manuel points towards the back of the Manuel homeplace in innłq̓iłmlx (Quilchena), a small community outside of the unceded homelands of the syilx and Nlaka’pamux peoples in what has been briefly known as Merritt, B.C.

Juanita Lindley sits in the shade of a big tree — the last one standing amid two other large trees that were struck down by lightning just the night before. At first, the rain is sprinkling with the sun occasionally peeking through. Then lightning and thunder fills the sky and air around us as she shares her story.

“I haven’t been able to leave this spot; I just sit here all day,” says Juanita. She looks out on an open field, dotted with hay bales and a treeline where a creek flows through.

Juanita recently returned home after the family had spent days searching for their beloved Kwemcxenalqs Manuel-Gottfriedson in “English Bay” after the Celebration of Lights firework show in the unceded homelands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and səlil̓wətaʔɬ. On July 30, Juanita’s first-born child was found, already on their journey to the Spirit World.

“Being stripped of everything, I’ve never felt so humble,” says Juanita. “Like I just don’t need anything, you know, just your heartbeat … your breath, so it’s a good place to start to just be grateful.”

Kwemcxenalqs

Kwemcxenalqs was gifted an important name when they were born into this place and time. Throughout the evening and during the ceremony for Kwemcxenalqs, the family shared stories of how she lived up to her name.

“I was 18 when I found out I was pregnant; I didn’t know anything about having kids, I was too young still, but I knew instantly what I had to do,” says Juanita.

“I told my mom, [and she had me enter ceremony].” She points down to the creek where part of her ceremony while carrying Kwemcxenalqs took place.

It was some time into Juanita’s pregnancy ceremony with Kwemcxenalqs when her mother told her to go see her uncle Herbie Manuel, who was the Hereditary Chief at the time.

“Uncle Herbie points at my belly and says, ‘that one there is going to be born with a sqilx’w skwist, they’re not going to have an English name — no more babies with English names,’” Juanita shares.

“My mom said, ‘you’re not going to choose your [baby’s] name,’ so I wasn’t even a part of it. My grandma Laura, she dreamt her name, and her name was both of her great-grandmother’s names — so she was Kwemcxenalqs … Rainbow Dress Woman.”

Kwemcxenalqs was the first sqilx’w to have only a sqilx’w skwist (Indigenous name) in her community in more than 60 years.

Nexpetko, Kwemcxenalqs’s sister, says that her name was an important part of her identity.

“Her name really embodied who she was,” says Nexpetko. “She was just such a bright person, like the rainbows after the rain; whenever I’d be down, she would come and make it better.”

Roipellst, Kwemcxenalqs’s brother, also shared that his sister was full of love and lived life for her people.

“She had good morals and a vision for her community, but she just never got to fully express that while she was here,” says Roipellst. “She was always the one to give people that benefit of the doubt because she believed that everybody needed to be loved the same.”

Kwemcxenalqs’s family shares through many stories that even in her silence, she was powerful — she carried the sqilx’w way of accepting and loving each person and honouring their purpose.

“She was very spiritual with the way she moved and viewed life and enjoyed all cultures,” Roipellst says.

“[She] wanted to help other cultures who aren’t Indigenous to these lands to make them feel comfortable and at home and accepted on this land and try to explain things the best she knew how.”

Kwemcxenalqs stood in her sacredness. Being the first to hold only a sqilx’w skwist, without English in it, since residential “schools” meant she had a responsibility to be strong in her sovereignty and who she was. While she was impacted by colonization, the tongues of her oppressors continued to struggle to pronounce the powerful name she held.

“I don’t want people to see her as just another woman that’s gone missing. Because she’s more than that, she’s sqilx’w,” shares Nexpetko, with growing strength in her voice.

“So don’t pity her; she’s not someone to be pitied. And in turn, that goes for all sqilx’w people. We aren’t people who want to be pitied. … She was strong sqilx’w women — strong and beautiful.”

‘Our mental health is so sacred’

The thunder continues to roar, and the rain cleanses the air, carrying moments of calm as Juanita carefully takes her time to share more of her daughter’s story.

“Our mental health is so sacred,” says Juanita, who is also a grief worker.

“When we pass, of course we are sad, but it’s part of the human experience and the lessons that she leaves behind … there are lessons in the way of our agreements that we make with Creator about how we’re going to leave when we’re going to leave, and why we’re going to leave, the grief is part of that transformation. We are sacred during these times and grief brings change,” Juanita shares.

“And as I experience all of this, I still believe that. I’m grateful to have been entrusted with her, she was greatly loved.”

Nexpetko says that during her time with Kwemcxenalqs on this earthly plane, the lessons she brought her were the importance of love, laughter, and what it means to carry strength peacefully.

“She just loved everybody, and she was friends with everybody. You couldn’t meet her and not fall in love with her. She loved everyone, animals, the land, and our people,” Nexpetko shares.

Whether it was during a kitchen dance party between the sisters, or swapping stories of love, Nexpotko remembers she would watch her sister with admiration — the way she carried herself with such independence and grace. She would sometimes sit quietly around the corner, hoping Kwemcxenalqs wouldn’t notice her so that she could listen to her in her own space, singing to herself, because it was so powerful.

“And that’s her sovereignty,” Juanita says. “She was always adamant about her space and who she was.”

As Juanita looks out over the field, the rain picks up, and she starts to close her story.

“I don’t know how low [the grief] gets yet, or what it’s going to be like, but I stay to live for my kids, I love them so much, and that’s all I have to hold onto right now,” she says.

“I know at some point in time I’ll get up again, but until then, I’m just going to sit here.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

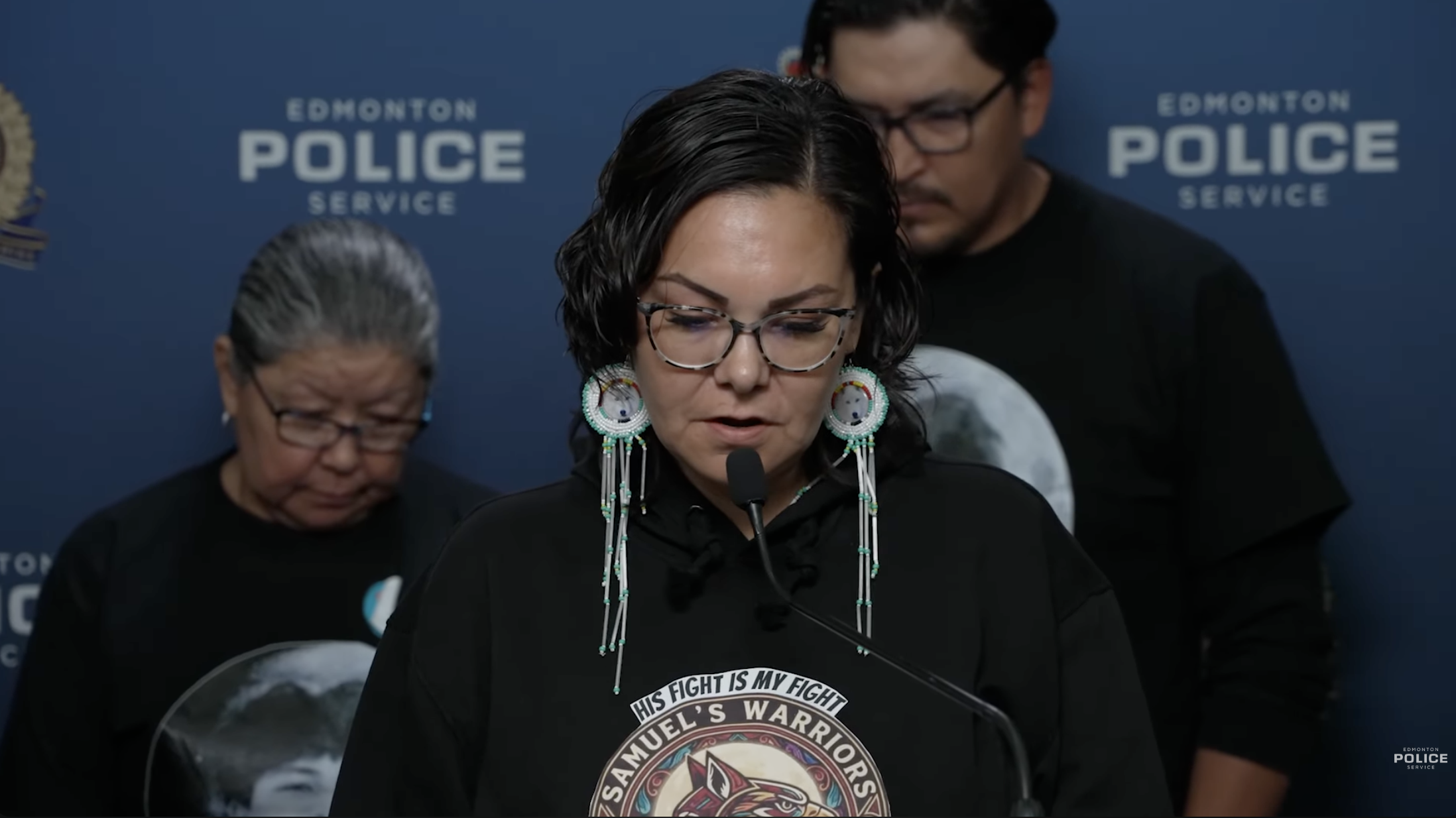

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death

-

Book remembers ‘fighting spirit’ of Gino Odjick, hockey’s ‘Algonquin Assassin’

Biography of late Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg left winger explores Odjick’s legacy as enforcer in the rink — and Youth role model off the ice