Beyond tokenization: Why inclusivity of Indigenous people can be life or death

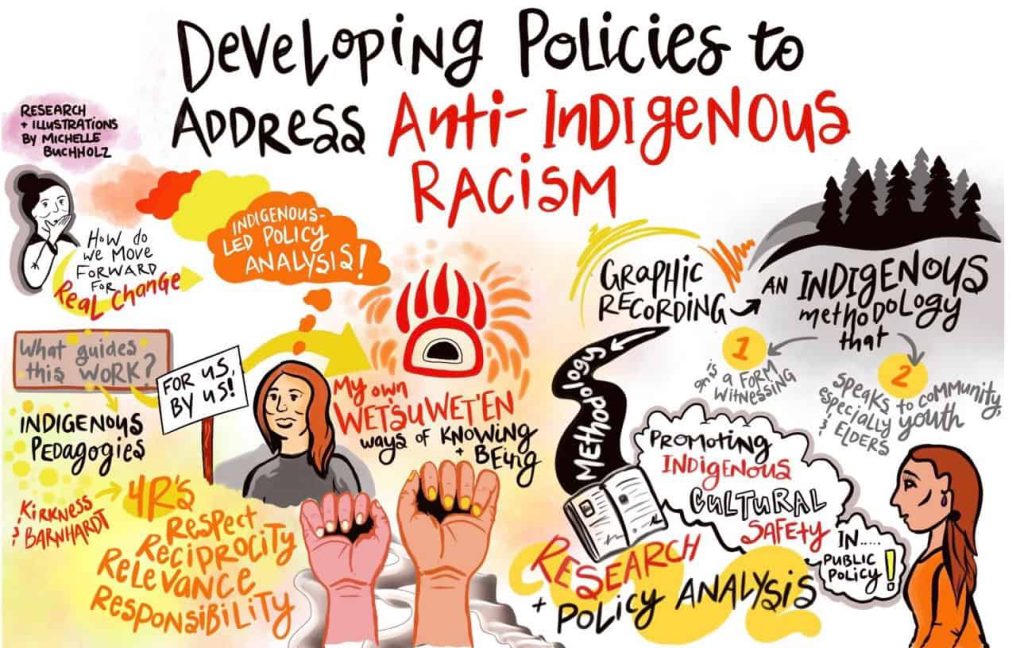

Michelle Buchholz illustrates what inclusion really means — engaging Indigenous perspectives throughout policy and decision making.

Michelle Buchholz is clear about what meaningful involvement of Indigenous people in policy and decision making should look like.

“Inclusivity, with Indigenous people, it’s not just about making us feel good. It’s about saving lives. Really. It comes down to that,” she says.

Buchholz is a Wet’suwet’en woman from the Cassyex (Grizzly Bear) House and the Gitumden (Wolf) Clan. She holds a masters of public policy degree from Simon Fraser University and has a background in Indigenous studies as well as Indigenous research and methodologies.

A co-op placement with Provincial Health Services Authority (PHSA) gave her the lens of healthcare to explore inequities impacting Indigenous people.

“We are not doing as well as the rest of the country,” she says, referencing the many studies on these inequities, and social determinants impacting Indigenous health.

“Why is that? A lot of the research points to anti-Indigenous racism,” she explains.

“It’s so strange to me that people don’t like to acknowledge it or that there’s different language to dress it up, with a word like oppression and discrimination.”

Buchholz thinks about this from the perspective of critical race theory.

“Anti-racism theorists state that racism is endemic to society and Indigenous race theorists say that colonization is endemic to society… It really is a part of how our structures were built,” she says.

Avoiding tokenization

On Oct. 29, Buchholz hosted a workshop called “Facilitating Safer, Braver, and Inclusive Virtual Spaces,” focused on how to avoid tokenization and have inclusive conversations at work.

“Reconciliation has led to increased awareness among all professions, and a realization that there has been a lack of inclusion,” said Buchholz in an interview with IndigiNews after the event.

When Indigenous people are invited to participate in events, it’s important to make sure they aren’t just a gesture to reconciliation she explains.

Buchholz gives the example of events where Elders are invited to open a conference, and then asking them to leave after the welcoming.

“Our bodies are welcome as Indigenous people, but then our experiences and our protocol is not. And to me, that is tokenization.”

Proper Elder care includes how to genuinely engage Elders’ perspective, Buchholz says. In addition, ensuring that they have transportation to and from an event, and that they are paid a proper honorarium.

“Particularly in universities,” Buchholz recommends. “Not just asking them to come and talk a little bit about the culture and then leave. Keeping them part of a curriculum and really being meaningfully involved in policy making and all of the things that make up the university experience for students.”

One example of good practice Buchholz shared was from PHSA engaging a circle of Elders for their support and guidance on a new program to support pregnant women using substances. Elders were involved in “everything from creation of documents, to looking at policies and how the events should be conducted,” she explains.

Another way to make sure people aren’t tokenized is to give people a real voice at the table.

Part of that, Buchholz says, is that people understand the difference between learning about culture and acknowledging systemic racism.

“[We need] less focus on people being aware of our culture, and more focused on contractual policies so that our people aren’t being harmed anymore. This is something that’s been happening since the start of colonization,” she says.

“One way we can address [systemic racism], we can make actual contractual policies to address, to think about that decision making process, who makes the decisions?”

Buchholz has given this a lot of thought, given her direct experiences with “wanting to sit at decision making tables but really being kind of shunned out of them because of being young, being Indigenous, and being a woman.”

She wants Indigenous people to be given leadership opportunities. “[Include] Indigenous people in those health policy decision making tables, why can’t it be an Indigenous person leading various departments?” she asks.

“[We need] less focus on people being aware of our culture, and more focused on contractual policies so that our people aren’t being harmed anymore. This is something that’s been happening since the start of colonization.”

Graphic Recording, a way to witness

As a policy analyst, facilitator and illustrator, Buchholz has found a new way to communicate, through what she calls visual policy analysis.

Buchholz takes her research knowledge and then turns information into illustrations that are easier for people to understand.

“I wanted to be able to share the research with my community and, sending them a 50 page report wasn’t ideal. I wanted to synthesize it, make it really appealing and colorful, using visuals,” she says.

She describes this work as graphic recording and explains that it’s a way of witnessing, similar to the witness role at Wet’suwet’en gatherings. At denii ne’aas, where business and governance is conducted, paid witnesses serve as recorders in an oral tradition. The Wet’suwet’en word for feast, “denii ne’aas” means “people coming together,” although people also use the word potlatch, according to the Office of the Wet’suwet’en website.

If Buchholz is serving as graphic recorder for a workshop, she uses visuals and texts to show the witnessing of the day’s events. It involves genuine listening to highlight the key messages, she explains.

In a world and time filled with competing priorities, Buchholz grounds herself by prioritizing community.

“Whether we’re talking about the Black community, Indigenous communities, urban or rural. And so really drilling down to the local level,” she says, “it’s easiest to start.”

Buchholz hopes that Indigenous youth continue to “move really gracefully into those leadership roles,” and, she adds, “but not just leadership roles, that more Indigenous folk go into these realms where our voices really aren’t heard: politics, public policy, director roles.

“My hope is that Indigenous knowledge is really respected and revered as impactful in future public policy, research, facilitation, healthcare and in everything.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

St. Augustine’s survivor hopes for closure after evidence of 81 unmarked graves released

50 years after the residential ‘school’ closed, shíshálh Nation announces evidence of many burial sites. A Tla’amin Elder wonders how many more children died