Comox Valley educator wants Indigenous youth to feel belonging and pride

Jeannine Lindsay, a new teacher and former Indigenous Support Worker, aims to give students the experience that she never had growing up

An Indigenous educator in the Comox Valley is aiming to give local students the inclusive schooling experience that she didn’t have growing up.

Jeannine Lindsay — a former Indigenous support worker and new teacher — was 13 years old when she first learned she had Indigenous ancestry. It was something that was kept hidden in her family for fear of shame.

When she had her son, who is now in Grade 8, it was a turning point for her, she says, because she realized she wanted him to be able to have a sense of belonging and pride.

“When I was in high school we didn’t talk about First Nations issues, social justice, residential schools,” Lindsay says.

“We didn’t learn about any of that.”

Lindsay comes from a diverse ancestry of Anishinaabe, Cree, Scottish and Irish bloodlines and is adopted Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw and Wuikinuxv. Her bloodline comes from the Tootinaowaziibeeng Treaty Reserve in Manitoba and Cote First Nation in Saskatchewan.

Lindsay’s Anishnaabe name is Aaabawasige and says she introduces herself this way to her students first.

Over the past five years, Lindsay has played a key role in integrating Indigenous culture and values into Comox Valley Schools as an Indigenous support worker. In 2018, she received a Premier’s Award for Excellence in Education for her efforts at Lake Trail Middle School in Courtenay, B.C.

That award motivated her to go after a Bachelor of Education degree at Vancouver Island University, which she recently completed. She has also been influenced by her mother, who was an educator.

“I really wanted to be able to have my own classroom and be talking about Indigenous issues, being able to teach First Nations studies, being able to teach social justice,” she says.

“Really helping to develop that out of my growth within the education system, but also for my son and future generations to feel comfortable talking about those kinds of issues because I feel like for a long time it was hush-hush and we weren’t supposed to be talking about it.”

Towards reconciliation

This past fall, Lindsay returned to Lake Trail Middle School for her practicum, where she hosted a reconciliation-focused workshop for Grade 8 and 9 students.

The workshop was part of the Youth Leading Reconciliation initiative, which is typically a Vancouver Island-wide conference where more than 100 students from various districts gather.

Comox Valley Schools have participated in the event that began in 2016 for the past three years, but this year things looked differently because of COVID-19. Lake Trail Middle School was the only school in the district to put on a workshop of their own, thanks to Lindsay organizing it.

Mary Lee, who is the manager of communications for Comox Valley Schools, says the conference is part of a wider effort by the school district to bridge the gap and work on incorporating the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendations.

“It’s for both (Indigenous and non-Indigenous students), so that they can create that dialogue,” she says.

“Creating that environment and mimicking that in a conference is exactly what we see every day … is that we’re culturally embedded together.”

During the half-day workshop in November, students spent time working on what they think it means to embrace the concept of reconciliation in their communities.

Within one afternoon, Lindsay says that the ideas the students shared showed that there was an understanding of what reconciliation was and that actions they take on a daily basis lead to reconciliation.

“We went in with the model that we wanted the youth within the classroom to be able to use to carry on the conversation and understand what reconciliation could look like,” she says.

“(It) can be being a good ally to Indigenous peoples, it can be having conversations, it can be learning about the cultural connections of the original inhabitants of the land that you live on.”

One of the participants, Kadence Klassen, says she learned a lot in a short amount of time about the Indian Act and residential schools.

“And how it was just wrong what we’ve done and how we should just change it and try not to repeat those things,” Klassen says.

Another participant, Liam Thomson, says he recognizes that Canadian history is more grim than many people realize.

“Everybody thinks that we’re so great but there are a lot of dark corners in our history,” he says.

Looking forward

Lindsay says she is proud to work for the Comox Valley School District, where integrating culture is now “normalized,” in classrooms, she says. Her son has even been learning to bead at school.

“There are land acknowledgments and there is sharing of cultural protocols in classrooms and it’s not something that is looked upon as out of the ordinary, it’s expected and normalized here,” she says.

Eventually, Lindsay says she would love to go back to complete a master’s degree so that she can help create programming for Indigenous education, but for the time being she is happy where she is and looks forward to organizing more events such as Youth Leading Reconciliation.

“This type of workshop would be beneficial for everybody within a school district, not just youth,” she says.

“I believe that we’re all in this journey together and that reconciliation isn’t an Indigenous issue, it is something that we’re all working towards.”

Katłįa (Catherine) Lafferty is an education reporter for IndigiNews on Vancouver Island. You can follow her work here.

Editor’s Note, Jan 6, 2021. A previous version of this story stated that she grew up on the Tootinaowaziibeeng Treaty Reserve in Manitoba and Cote First Nation in Saskatchewan. That is incorrect. The story has been edited to state that Her bloodline comes from the Tootinaowaziibeeng Treaty Reserve in Manitoba and Cote First Nation in Saskatchewan.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

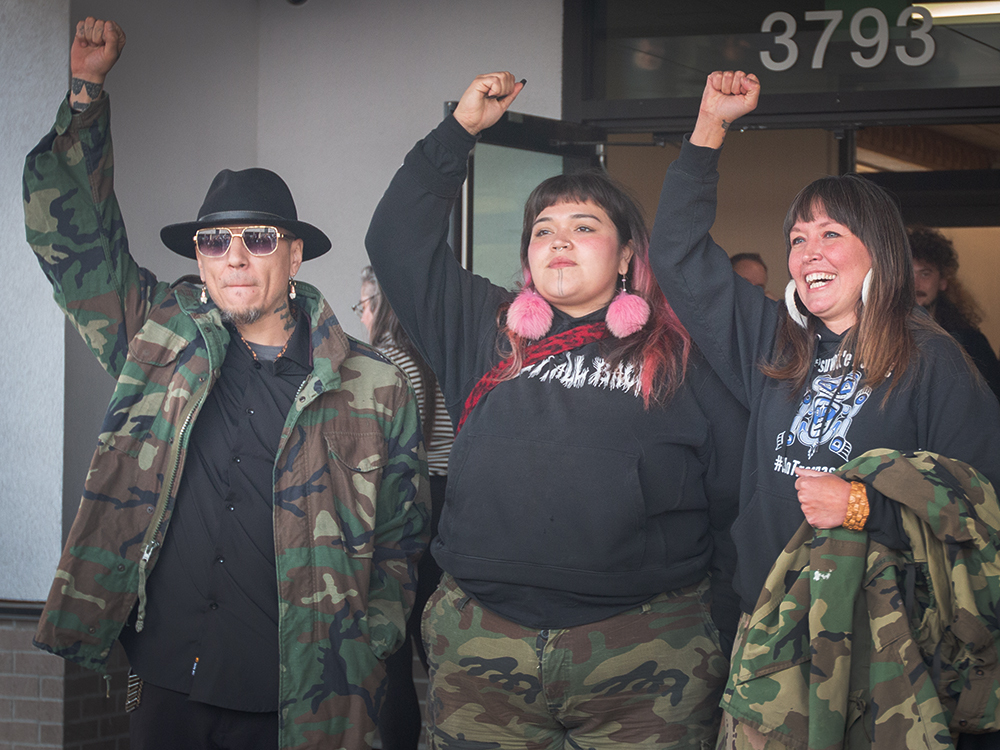

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

-

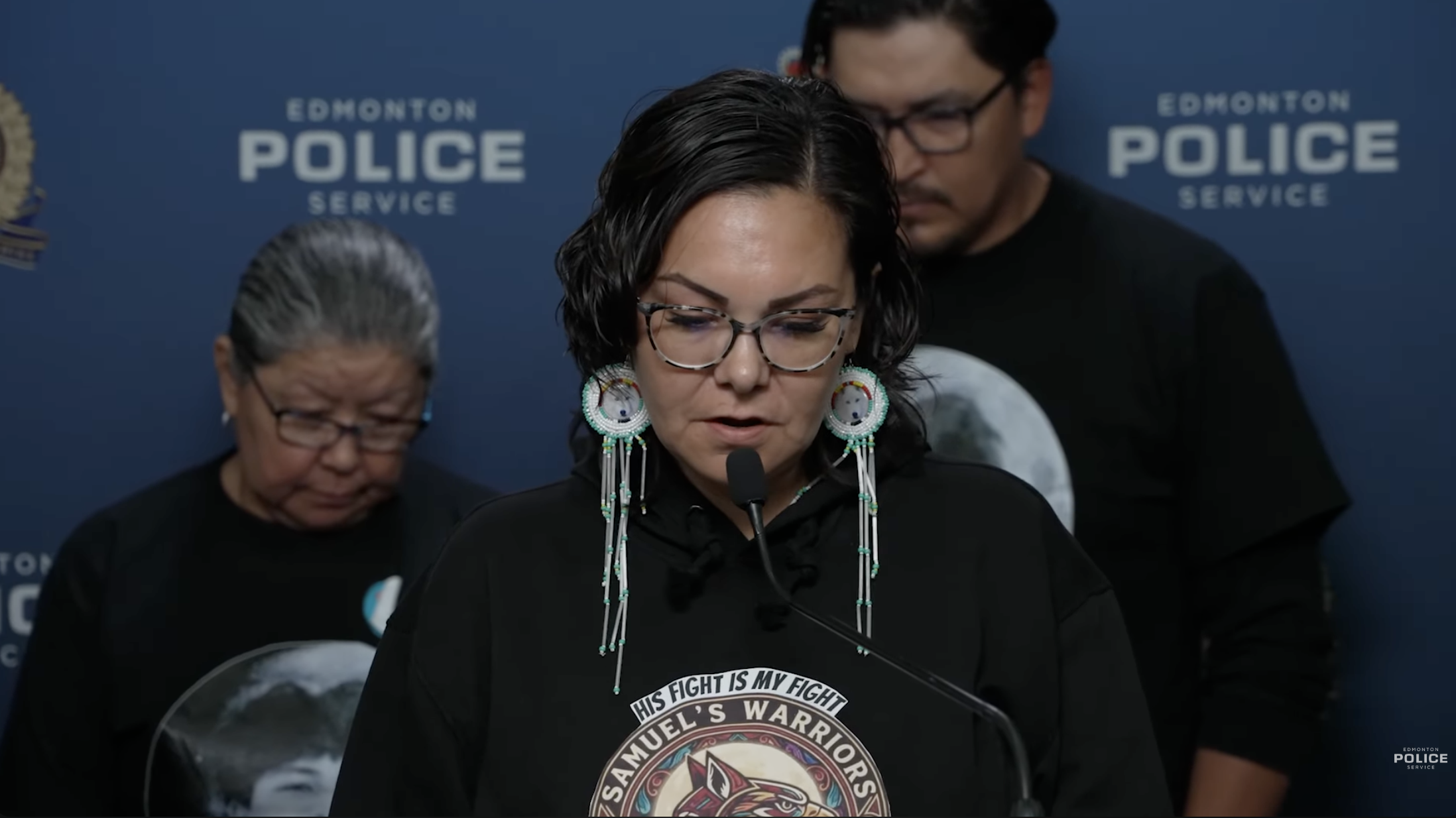

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death