Indigenous people: take care, non-Indigenous people: take action, everyone in-between — do both.

A message from IndigiNews managing editor before reporting on residential “schools”

This article contains content about residential “school” that may be triggering. IndigiNews is committed to trauma-informed ethical reporting, which involves taking time and care, self-location, transparency and creating safety plans for those who come forward with stories to share.

I raise my hands up to IndigiNews reporter Kelsie Kilawna who has been leading the way in trauma-informed reporting, including asking reporters to self-locate, and take care, before reporting on residential institutions.

The process of locating ourselves — explaining who we are, where we’re from and how we’re connected to the subject we’re reporting on — is an important part of decolonizing journalism. While intended neutrality serves journalism in some ways, assuming that people can be objective, as if they haven’t been shaped by their families, cultures, societies and education systems, is false. This kind of thinking can prevent meaningful accountability and lead to inaccurate and even oppressive reporting.

IndigiNews was co-founded by The Discourse and APTN last year. Prior to becoming managing editor of IndigiNews in October 2020, I was asked to be an advisor on the project. I was told they contacted me because of my efforts to amplify conversations around decolonizing journalism.

Before taking on this role, I led a series called “First Nations Forward” by Canada’s National Observer, dedicated to stories of success, strength and self-determination in communities across the west coast of the country.

Some form of journalism or communications has run through my family for a long time and when connected, I’ve never doubted my responsibility to pick up the pen, microphone or camera, and to continue to tell the truth, raise awareness and document history in the making.

Knowing how and when to speak and when to listen is an ongoing learning journey for us all.

My great Uncle Ted Chartrand, who is currently in a period of transitioning at 95 years-old, once the best trapper in The Pas, had a video camera glued to his hand as soon as he got one. I’ve watched old videos of my family, captured through his eyes, and I see myself in him, the curiosity, the awe of life itself, and the desire to mark precious moments in time.

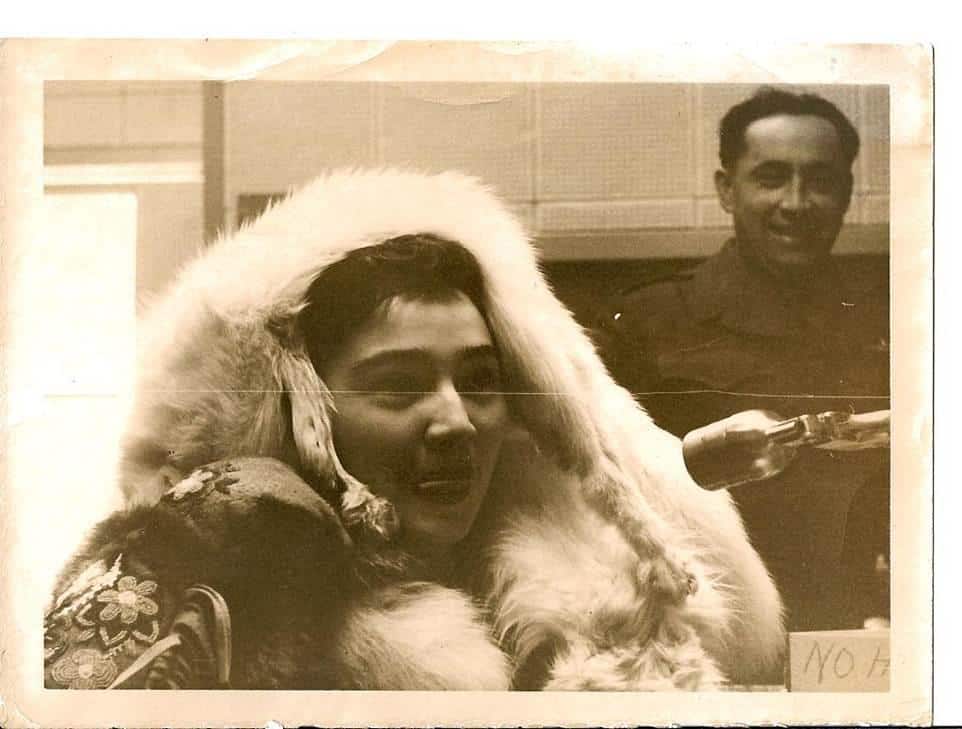

My late grandmother Irene Chartrand, often the star of her brother Ted’s short clips, had a stint as a radio DJ in Churchill, Manitoba in 1953-54. Born and raised in The Pas, despite the harsh climate and colonial practices she grew around, she was a confident woman, and I know she was causing all kinds of trouble on the airwaves. I often share this photo of her, with her brother laughing away behind her, because I see myself in it, in her. I’m told she mostly reported on polar bear activity, but after knowing her for over half of my life, I trust she used her voice for much more.

My late great Uncle Al Chartrand was once one of Manitoba’s Native Chief Court Communicators. He was also the founder and president of the Native Clan Organization, a non-profit that supports Indigenous “offenders and ex-offenders to reintegrate back into the community.” In 1975, he started Neechewan (meaning friend or brother in Cree), to support Indigenous youth in securing jobs and to help them avoid being incarcerated by a system set up against their success. I’m told he was a fighter for justice, like me, and I take pride in his ability to use his voice to find solutions.

There are too many family members to mention, but I remember these three now, for their determination to speak up and out.

I call myself a Michif nomad. I am Métis, Filipina, and third- and fourth-generation settler. My mom’s family comes from Ireland and Scotland. I have mostly Cree, but also Saulteau and Ojibwe relations through my Métis side. While all of my Métis family comes from or continues to reside in The Pas, I was born and raised in London, Ontario, the traditional territory of the Anishinaabeg, Haudenosaunee, Attawandaron, and Wendat Peoples. I left London at 17 years-old, and have been nomadic ever since, living in Hamilton, Montreal, Vancouver, Central and South America, and now in W̱SÁNEĆ territory, just outside of so-called Victoria, B.C.

My grandmother didn’t attend a so-called “Indian Residential School” — otherwise known as a forced-assimilation institution — but she did attend a day “school,” where she was forced to sit at the back of the class and labelled a “savage.” My family is still researching whether or not she had dental and medical experiments done on her, which likely contributed to her life-long health issues and ultimate passing. She kept quiet about some of her earlier experiences, and she left The Pas and the extreme assimilative practices taking place in Northern Manitoba with good reason. My father, a visibly racialized Métis and Filipino man, attended a Catholic school in Delaware, Ontario, where he experienced violent racism for the majority of his childhood.

I’m not going to get into the details here of how patriarchal, assimilative, colonial institutions like the Catholic Church and the Canadian government have drastically impacted myself, my family, and our connections to our cultures. Suffice to say that my cross-cultural experiences, values, teachings, and intergenerational wisdom all inform my writing, in a way that is both necessary and valuable.

I am not a pie that can be sliced into neat pieces. I have also inherited the strength and wisdom, and also the privileges of my mother, maternal grandmother and grandfather. With privilege comes responsibility, which is why my work is dedicated to restoring justice and shedding truth. My mother, who grew up barefoot on a farm, taught my sister and I the power of preserving your imagination, and it was from her mother and her love that we learned compassion and humility. These teachings also inform my relationships and my work.

I carry my Filipino grandfather and relatives with me as well. We are people from thousands of islands, with an understanding of the interconnection of living ecosystems and an indomitable sense of kinship.

As a mixed person who has been nomadic for half my life, I have learned to shape-shift, code-switch, and take my responsibilities as a visitor seriously.

I am the seeds my ancestors planted

If and when I report on the ongoing discovery of bodies on the sites of these horror institutions, I do so from the place of a Michif (Métis, mixed) person. I do so as someone who understands their responsibility to raise awareness in a trauma-informed, anti-oppressive and accurate way, and someone committed to balancing my privilege as a part-settler, white-passing person, with a responsibility to commit to varying forms of labour when asked and required.

In our newsroom, we often discuss when it is appropriate for us to cover a story, and how to do it in a safe, conscious and compassionate way. We have done spiritual work to clear low frequency energies of fear, self-doubt, shame, guilt and judgment, and we work together to carry on the work of our ancestors, to tell the truth that needs to be shared and to not repeat cycles of abuse, deceit and injustice.

Intention is crucial to the work of a storyteller, and my intention (despite the ways mainstream messaging rewards narcissism and self-promotion), is not to win a prize, attract clout or be rewarded. My intention as a storyteller is to use my strengths and skills to raise awareness, hold truth to power, and be accurate and accountable. My intention in my role as managing editor is to do everything in my power to support emerging storytellers, to create more space for Indigenous voices, and to plant seeds for a more just, equitable and sustainable future.

I saw a post by Adina Williams on Twitter that read: “Indigenous people: Take care. Non-Indigenous people: Take action,” to which I responded: “And those of us in-between: do both.”

I am grateful to work with a team of thoughtful, strong, fearless storytellers — Indigenous, non-Indigenous, mixed people — committed to holding truth to power, and not causing more harm, while valuing accountability in our practice.

Over these next few weeks, reporter Kelsie will be dedicating time and emotional labour to creating trauma-informed resources for anyone in the Canadian journalism industry to utilize. She’ll be drawing from her 15 years experience working in trauma-informed community-based spaces, as well as her experience reporting in her home community for IndigiNews Okanagan.

You can support Kelsie’s work to support the creation of trauma-informed reporting resources, as well as Kelsie’s ongoing reporting and efforts to decolonize journalism here.

A National Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former students and those affected. Access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866 925-4419.

Within B.C., the KUU-US Crisis Line Society aims to provide a “non-judgmental approach to listening and problem-solving.” The crisis line is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Call 1-800-588-8717 or go to kuu-uscrisisline.com. KUU-US means “people” in Nuu-chah-nulth.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

‘This is the vision’: Inside Nlaka’pamux Nation’s quest to build ‘B.C.’s’ first major solar project

As the province fast-tracks development, the Southern Interior tribal council has lessons to share on how to build for the future

-

Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Youth connect to their lands — and relatives — with annual Rez Ride

The Menmen tl’a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh mountain bike team pedals through ancestral villages — guided by Elders, culture and community spirit