T’Sou-ke man fuses the old with the new, sharing teachings with community

Jeff Welch, who has worked with local students in School District 62 for the past decade, explores the combination of tradition and technology in his teachings

Traditionally, a sharp stone tool was used by Coast Salish Peoples, to cut through the tough bark of a red cedar tree grown from a time immemorial. Nowadays, a hatchet will suffice.

The cedar is known as the ‘Tree of Life’ to the Coast Salish who have many uses for it, says Jeff Welch, a knowledge keeper from the T’Sou-ke Nation.

The cedar tree can provide for nearly every need, he explains — medicines, firewood, tools, canoes, mats, capes, skirts, waterproof baskets, hats, rope, fishing nets and house planks.

In exchange, people make offerings, not taking too much, only enough for what is needed and leaving the rest for generations to come, Welch says.

Land-based education

Welch was one of two T’Sou-ke First Nation members featured in a video by the Sooke Region Museum this summer in the middle of a dense forest in T’Sou-ke territory, teaching about the time-old harvesting practice.

If done properly, the stripping of the cedar’s bark will lend itself in one long thick strip, Welch explains. Harvesting is best in the summer, as sap flows steady from the warmth of the sun, covering over the fresh wound, forming a layer of protection once a strip is peeled off.

While still fresh and pliable the cedar must be worked and rolled before it dries, Welch says.

As fellow T’Sou-ke member Thor Gauti works to strip a section from the tree using a hatchet, Welch speaks about the practice of pulling, cleaning and preparing for weaving.

“When we strip a tree, only take one strip of cedar off for the entire life of the tree, so it will only have a minor wound to heal, instead of a huge wound that could kill the tree,” Welch explains.

“It will live for hundreds more years.”

Welch is a full-time traditional knowledge teacher, having worked with local students in School District 62 for the past decade. He also brings teachings to the University of Victoria.

During an interview with IndigiNews, Welch sits in a corner of the Sooke Region Museum, surrounded by cedar weavings created by his relatives.

He recalls sitting in the same area of the museum when he was younger. Nearby is a TV where he used to watch a video they had of his grandfather speaking about their traditional ways.

Now, Welch is called to district schools as an Indigenous mentor and gives presentations about cedar harvesting, weaving, and other cultural practices. He also takes students on tours through the territory, talking about fishing, plants and stories of the land.

“I basically unload everything I know on them,” he says.

He prides himself on being able to share a lot of information in a short period of time, and also for feeding one of the biggest species of octopus by hand once during a dive.

Welch says his favourite thing to teach about is harvesting techniques, because it’s something he’s naturally told others about since he was a child.

“I was taught to harvest my foods of all kinds,” he says. “And I would teach those who would go with me to harvest. So I’ve always been a teacher.”

Indigenous technologies

Prior to teaching about T’Sou-ke ways of knowing, Welch taught scuba diving.

He started in the year 2000 and stopped after about 600 dives, he says. After that, he started moving into the school district after being referred by T’Sou-ke Elder Shirley Alphonse.

“So I used my skills of instructing scuba divers, some of those skills, to teach my culture,” he says. “I found it hard at the beginning, it was very tough for me speaking in public, but I have been known to face my fears and conquer them.”

Welch says he wants to weave his teachings into the future.

He believes it is possible to incorporate traditional ways and technological advancements in a complimentary way. In doing so, he hopes to fuse “the new with the old,” he says.

During his cedar bark stripping demonstration at the museum, for example, Welch spoke about how he and Gauti were using a hatchet to harvest the bark — traditionally, he says, stone tools would have been used.

In the same way, when he was building a cedar canoe years ago, he utilized traditional methods, but incorporated contemporary tools, such as chainsaws.

“First Nations have been adopting technology since time immemorial,” he says. “Some people today … feel we should be using traditional tools from a few hundred years ago, but [I think] that’s not the case.”

Welch believes it’s important to keep up with advances in technology, in order to not get “left behind,” as the world changes, he says.

“Our advancements from now into the next ten to fifteen years is going to happen so fast that it’s going to be hard to keep up with,” he adds.

“We are part of the future and we are leading the way in peace and harmony, and ways of taking care of each other and Mother Earth.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

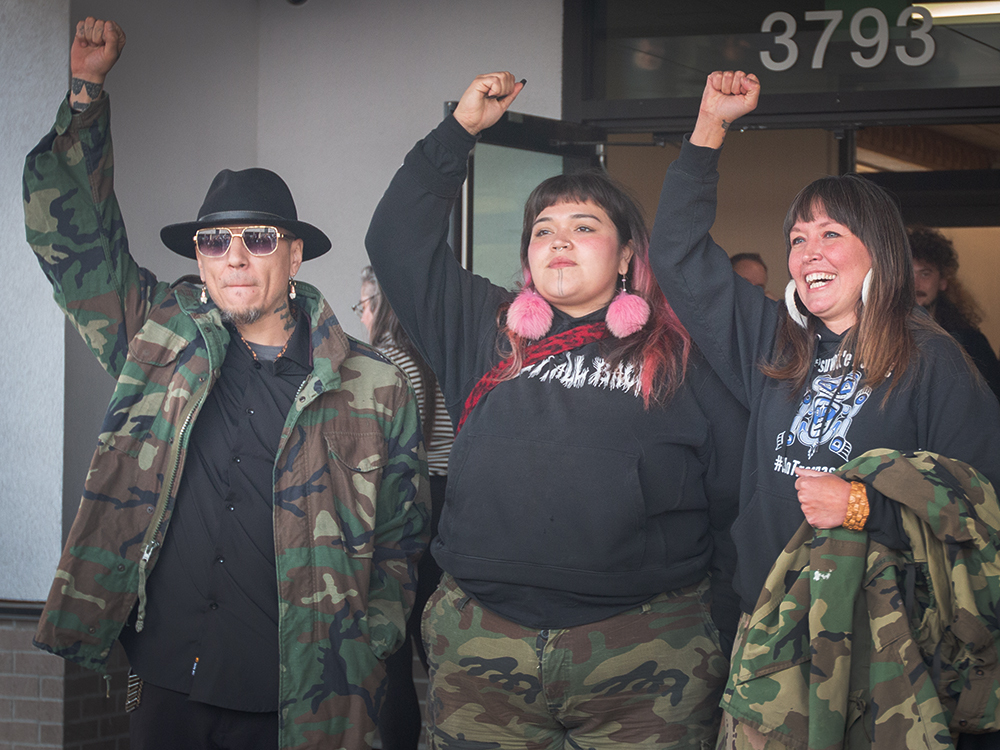

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

-

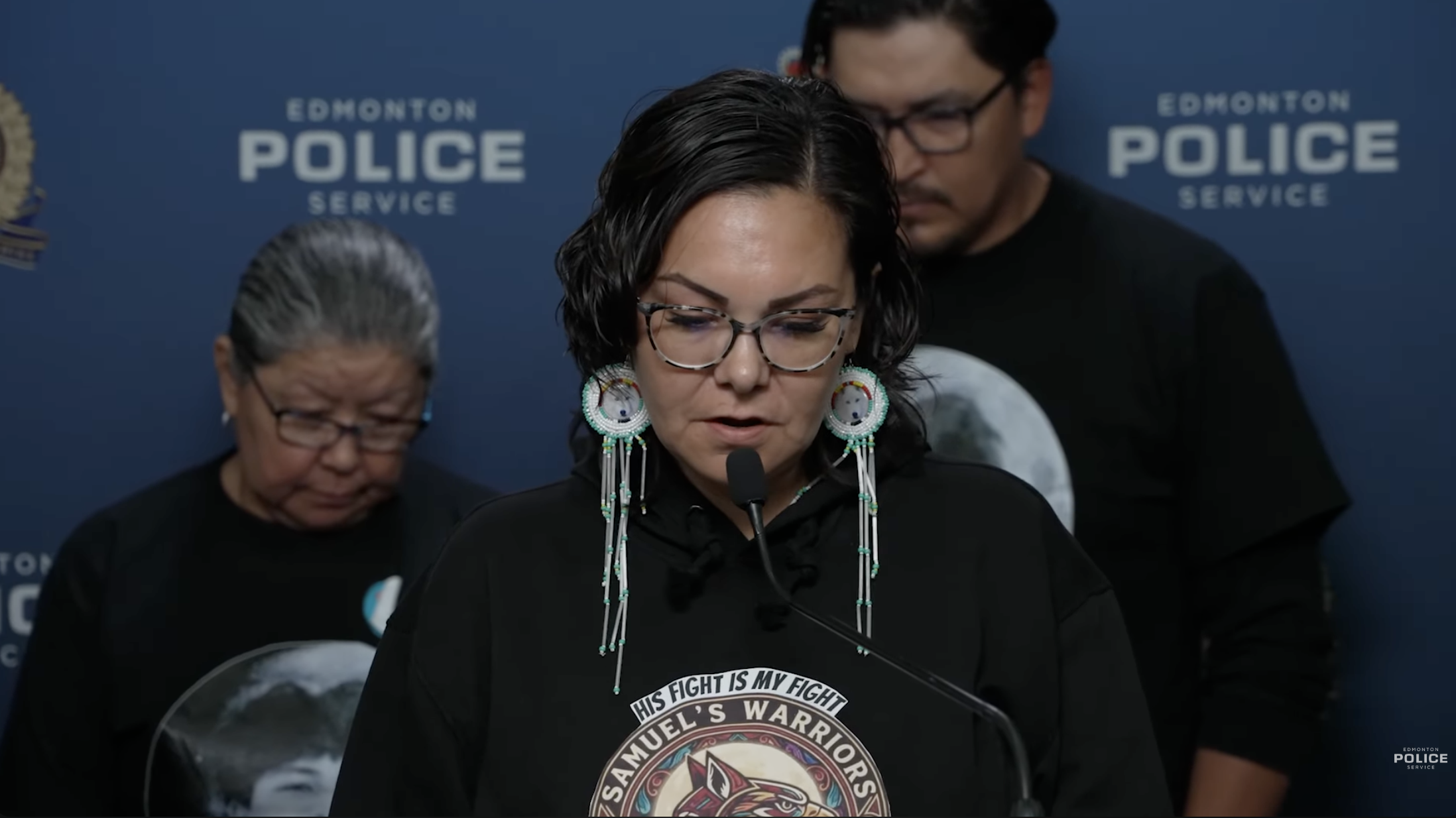

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death