A love letter to unhoused youth in Nanaimo

How a local magazine is creating a sense of place for youth experiencing homelessness

Across the country, people are being told to stay home or “shelter in place.” For unhoused youth living in so-called Nanaimo on unceded Snuneymuxw territory, the challenge of finding safe spaces and a sense of belonging during a global pandemic has been compounded by the overdose crisis and the displacement of the Wesley Street tent community.

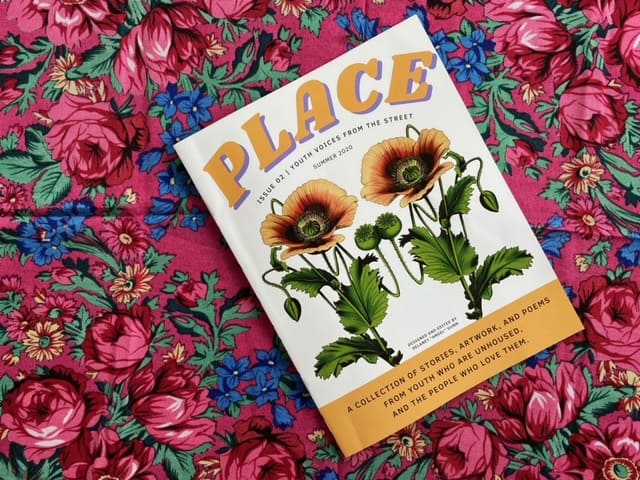

For Delaney “Angel” Gunn, the youth literacy coordinator at Literacy Central Vancouver Island (LCVI), the latest edition of PLACE magazine serves as a “love letter” to youth experiencing homelessness and to those who care for them.

Gunn was part of a youth outreach team that gathered stories for the magazine between May and December of 2020. The resulting publication features stories, art and poems by unhoused youth, many of whom were displaced from their homes when the Wesley Street tent community was dismantled on Dec. 4, 2020, says Gunn.

The magazine also features Elders’ perspectives, and essays by outreach workers who supported youth while they were being displaced.

The magazine aims to “uplift the voices of those affected by colonization most, and to celebrate the power of young people, their resiliency, and their creativity.”

“I wanted something visually beautiful to come from a really, really awful year,” Gunn says.

Wesley Street displacement

“When COVID-19 happened, we realized our community has literally zero services for people who are 15 to 30ish and all of the services that were available were geared at, like our Elders or seniors on the street,” Gunn says.

Gunn worked with members of the Nanaimo Aboriginal Centre’s Youth Advisory Council to form a mobile youth outreach team focused on delivering supplies to young people in the downtown area who were unable to access services or shelters.

“As we delivered supplies, we also made space to listen to stories of people living on Wesley Street,” Gunn writes in the magazine.

The Wesley Street tent community was located in downtown Nanaimo, adjacent to Nanaimo City Hall.

“This encampment started as a small cluster of shelters in 2019 a number of months after the closure of the Port Drive Tent City,” according to a statement from the Nanaimo bylaw department.

“As things usually go, the encampment grew in size over time, and began to develop many of the same characteristics that made the Port Drive Tent City untenable,” the statement reads.

After a fire broke out on Wesley Street on Dec. 3, 2020 — reportedly destroying multiple tents and triggering “a number of propane tank explosions,” — the Nanaimo Fire Rescue issued an order requiring occupants to “be dispersed.”

“Due to the ongoing risk and danger to occupants and the public, the encampment has been removed and the street is being reinstated to a clear state,” reads a statement from the City of Nanaimo on Dec. 4, 2020.

In PLACE, youth and Elders who were “displaced from Wesley Street” share their perspectives.

“I wanted to affirm everybody who witnessed — on the ground — what happened,” says Gunn. “And I wanted to preserve it. I think it’s, you know, it’s politically important. I think it’s just emotionally important for our clients.”

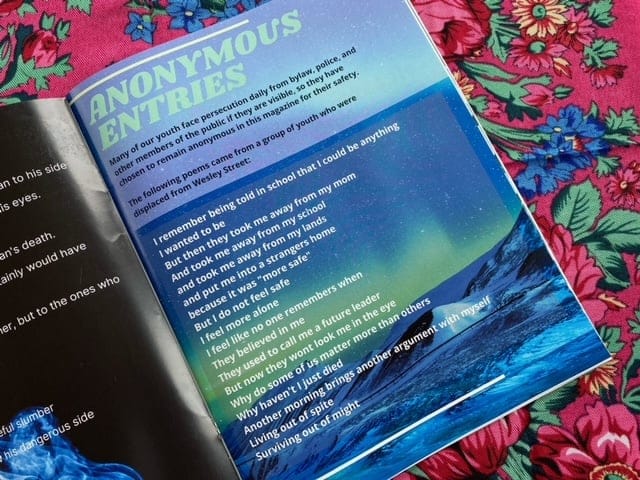

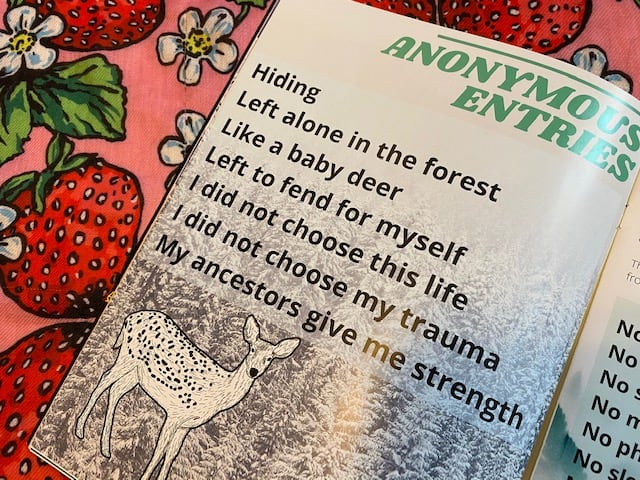

“Left to fend for myself, I did not choose this life. I did not choose my trauma. My ancestors give me strength,” writes one youth, who chose to remain anonymous.

Some folks with lived experiences contributed to the magazine anonymously, for safety reasons, explains Gunn.

“If our youth are visible, there are locals in Nanaimo who seek out homeless youth to beat up, or even set their tents on fire,” they say.

“I am a Nanaimo resident,” writes an Elder. “I was born and raised here. My mother was born and raised here. I am not going away.”

Multiple pandemics

The dismantling of the Wesley Street tent community is hardly the only challenge unhoused youth have had to deal with over the past year, and Gunn wanted this complexity to be reflected in the magazine.

“We are experiencing record numbers of overdoses in our province,” Gunn says.

A report by the Coroners Service of B.C. says that there were 1,548 illicit drug toxicity deaths in B.C. in 2020.

“I wanted [the magazine] to feel current to the fact that we are working through multiple pandemics at once … the COVID-19 pandemic, the housing crisis and the overdose crisis,” they say.

“If not for the action of a nearby friend, it most certainly would have been a very painful end. Not only to the life of a father, friend, and brother, but to the ones who tried to save [him] from being just another number,” reads a piece from Amy Chalifoux, a local poet and advocate.

The impacts of the overdose crisis are represented not only in the stories, but also in the artwork.

The magazine’s cover features two poppies designed by Lenae Silva, who co-runs the peer-run Open Heart Collaborative, which provides trauma-informed care, outreach and advocacy for “the most marginalized in our community.”

“Ideally, we could have a 24-hour drop-in center for youth in this community because they need a physical place to go,” Gunn says. “But, you know, I couldn’t offer them a physical place to go, so that’s where the name of PLACE magazine came from.”

The magazine is available at the Literacy Central Vancouver Island and the Vault Cafe in Nanaimo for $10, and all proceeds will go to future publications of the magazine and to the Youth Literacy Program.

Since the Wesley Street community was demolished, Gunn says they have lost touch with many of the youth they worked with during their outreach, but they see them as “amazing examples of community care.”

Gunn says they want displaced and unhoused youth to know they are “not alone” and the “community wants them.”

”You are literally the most crucial members of our community, especially Indigenous youth.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

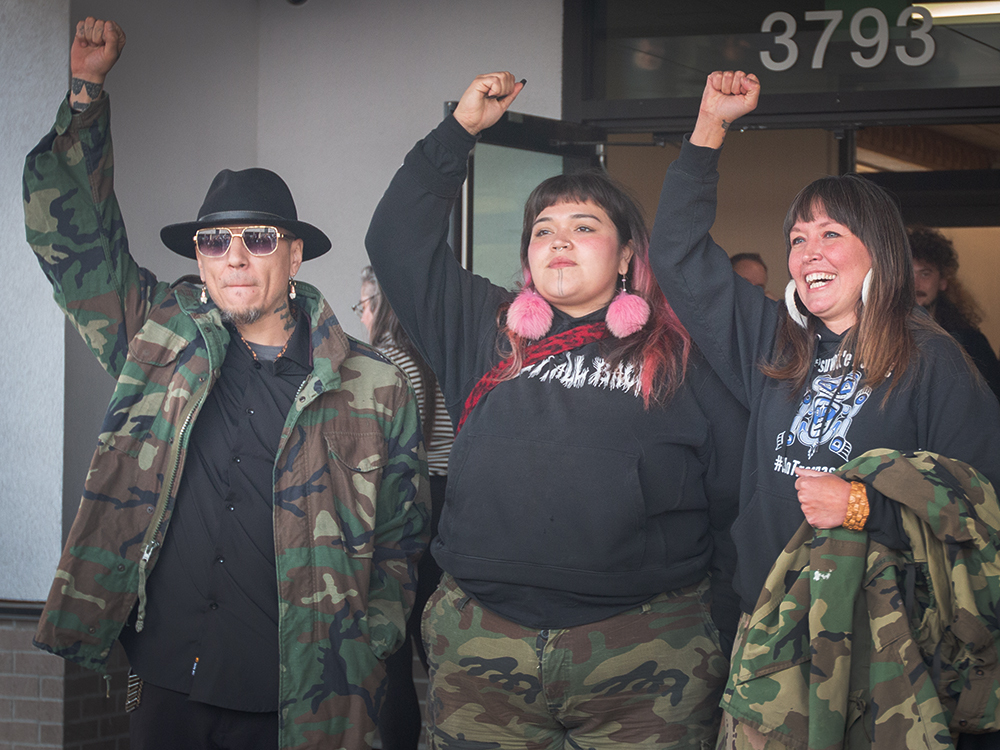

Land defenders who opposed CGL pipeline avoid jail time as judge acknowledges ‘legacy of colonization’

B.C. Supreme Court sentencing closes a chapter in years-long conflict in Wet’suwet’en territories that led to arrests

-

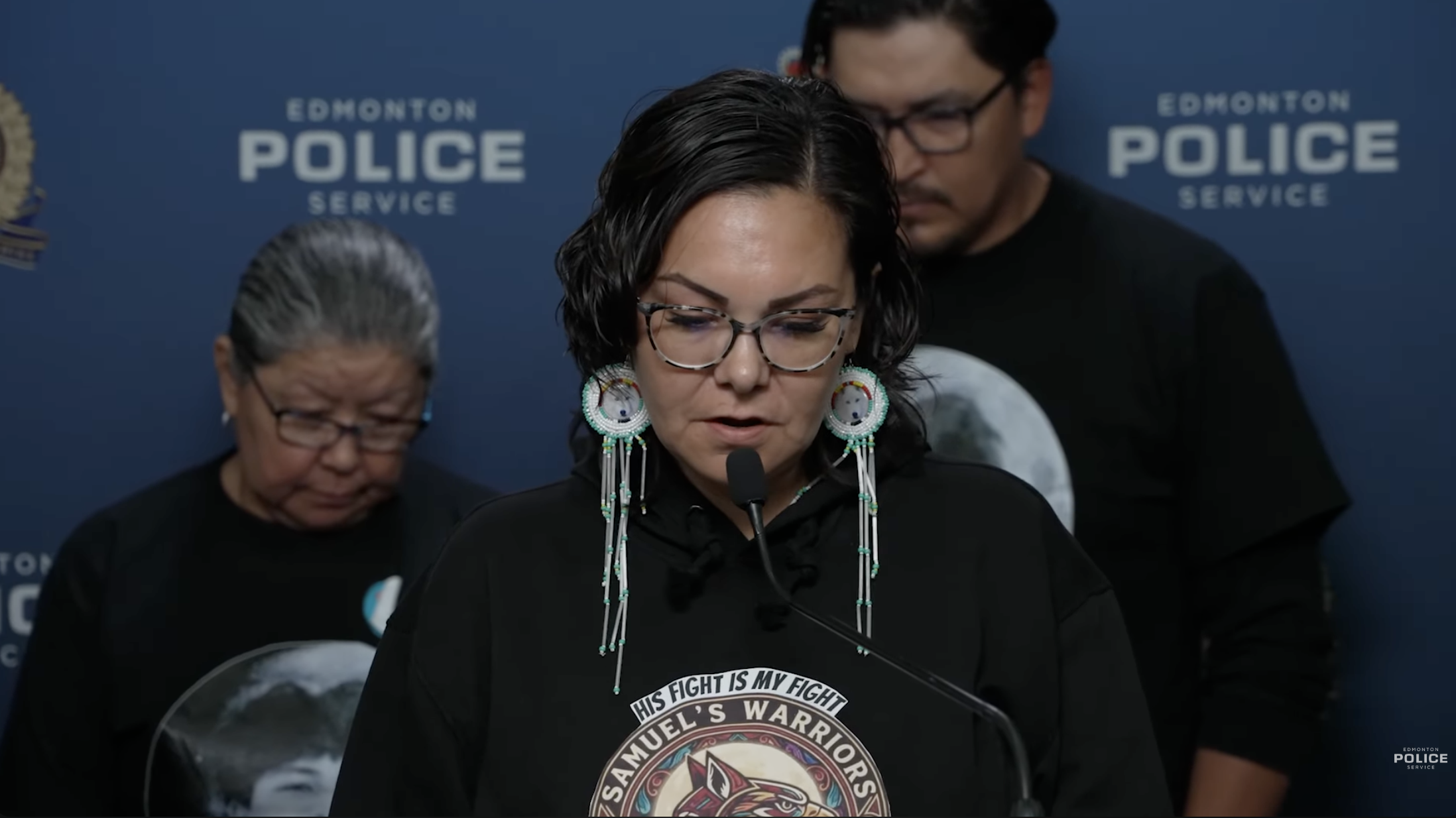

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death