Report details ‘intimidation and harassment’ of Wet’suwet’en people by RCMP protecting pipeline company

Amnesty International investigated human rights abuses by police, government, private security and CGL and is now calling for a halt of operations

Content warning: This story includes accounts of police violence against Indigenous people. Please look after your spirit and read with care.

Amnesty International is calling for a halt on any operations of the Coastal GasLink (CGL) pipeline in Wet’suwet’en territories after documenting years of human rights abuses against land defenders and their allies.

The international human rights group is also asking both “Canada” and “British Columbia” to immediately drop criminal contempt charges against protestors who they say were wrongly criminalized for exercising their Indigenous rights and their rights to freedom of peaceful assembly.

These recommendations and others are part of a new Amnesty International report which details accounts of alleged surveillance, harassment and intimidation from RCMP and security enforcing a B.C. Supreme Court injunction to protect CGL.

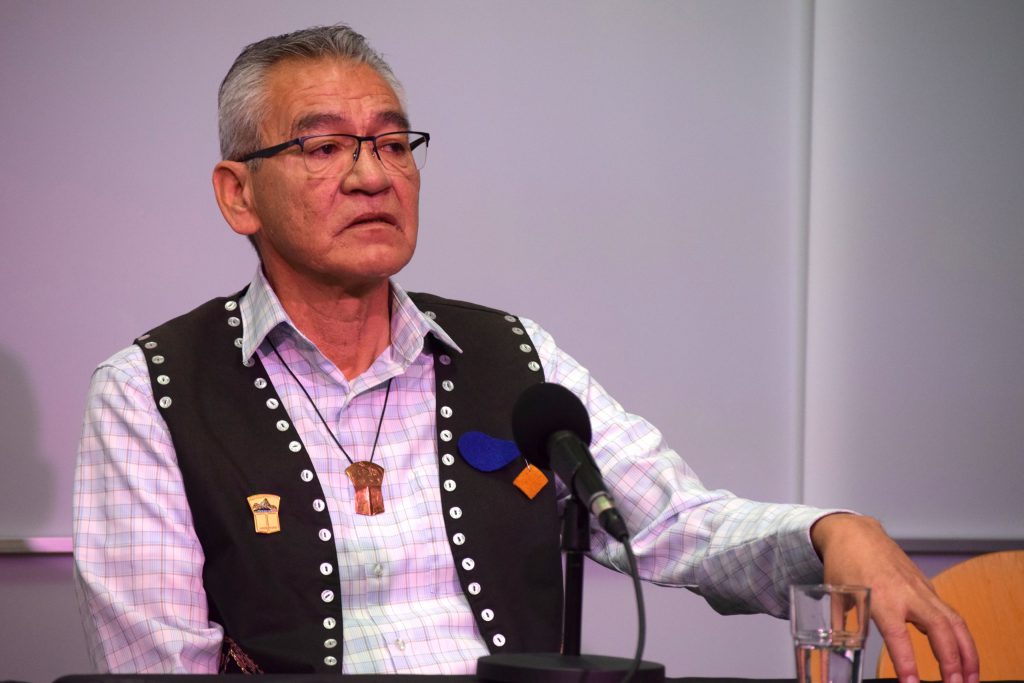

Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chief Na’moks said “Canada’s” human rights abuses in his homelands must be brought to light and referenced his nation’s laws that centre around protecting Mother Earth. Hereditary chiefs from all five Wet’suwet’en clans oppose the project under their jurisdiction.

“Canada itself (is) saying that we are criminals for being Wet’suwet’en, for fighting to drink out of the waters that are on our lands,” he said during a press conference in xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and səlilwətaɬ territories on Monday.

“You shouldn’t have to live with violence on a daily basis. The toll that takes on you physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually can’t even be comprehended. And yet Canada is saying it’s a great country.”

‘A concerted effort to remove them from their ancestral territory’

The ‘Removed from Our Land for Defending It:’ Criminalization, Intimidation and Harassment of Wet’suwet’en Land Defenders report was released on the 26th anniversary of the Supreme Court of Canada’s Delgamuukw v British Columbia ruling, a case that reaffirmed Wet’suwet’en customary law.

The research looks at the consultation process for the CGL project, saying it did not meet the criteria developed by international human rights law and standards. It then delves into an injunction order and how it led to violent enforcement involving RCMP raids.

“A court injunction requested by CGL Pipeline Ltd. and granted by the B.C. Supreme Court has served as the legal justification for the RCMP raids and other forms of criminalization suffered by Wet’suwet’en land defenders and their supporters,” according to Amnesty International.

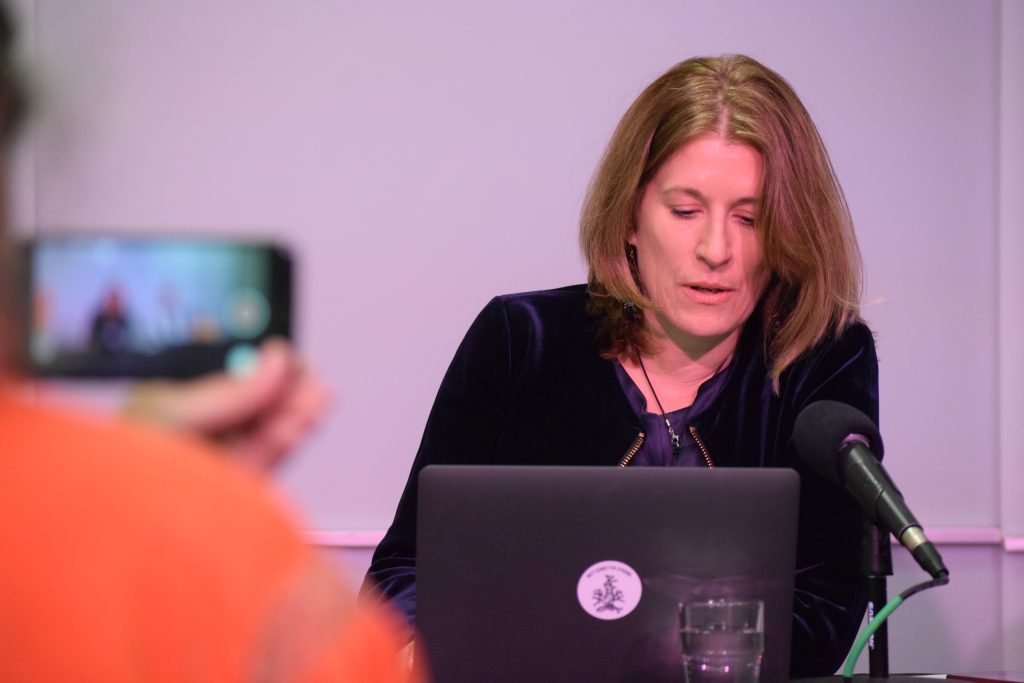

Ketty Nivyabandi, the secretary general of Amnesty International’s English-speaking section, said her organization investigated human rights violations at Wet’suwet’en for several months.

“Our research findings reveal that the Wet’suwet’en Nation continues to suffer severe violations of its internationally recognized rights,” she said.

“The right to self-governance, the right to free prior and informed consent and the right to make decisions related to its territory and its resources.”

The research involved interviewing people on the frontlines, including 22 Wet’suwet’en land defenders, reviewing court documents, United Nations reports, and more.

“So what emerges clearly from our report is that the intimidation, the harassment, the unlawful surveillance and the criminalization of Wet’suwet’en land defenders were part of a concerted effort to remove them from their ancestral territory in order to allow the pipeline construction to proceed.”

Wet’suwet’en people detail harassment

Between January 2019 and March 2023, there were four large-scale RCMP raids targeting Wet’suwet’en land defenders and their supporters — during which officers were equipped with “semi-automatic weapons, helicopters and dog units,” Nivyabandi said

The report emphasizes a December 2019 interlocutory injunction that banned land defenders and their supporters from blocking the Morice forest service road. That injunction order included an enforcement clause authorizing the RCMP “to arrest any person that they have reasonable and probable grounds to believe is contravening the injunction.”

France-Isabelle Langlois, the executive director of Amnistie Internationale Canada Francophone, said the overly broad injunction led to the arrests of more than 75 Wet’suwet’en and other land defenders solely for exercising their Indigenous rights and their rights to freedom of peaceful assembly. Several were charged with criminal contempt.

“Amnesty International calls on the authorities of Canada and British Columbia to ensure that injunctions are not used to restrict the human rights of Indigenous Peoples and that the criminal contempt charges against Wet’suwet’en and other land defenders are dropped without delay,” she said in a press release.

According to the report, tactics used by the RCMP during the four militarized raids on Wet’suwet’en were also disproportionate to the situation they were responding to, as there is no evidence of land defenders using violence or representing a threat.

During the first high-profile raid in January 2019, the RCMP arbitrarily arrested 14 land defenders in an operation involving about 50 heavily armed officers, helicopters, and surveillance drones, the report states.

In the subsequent raids in February 2020 and November 2021, the report notes the RCMP deployed dozens of officers armed with semi-automatic sniper rifles, dogs, bulldozers, and helicopters. Land defenders reported being assaulted during arrests, with officers wearing masks, refusing to identify themselves, destroying land defenders’ property and cutting off communication channels among the defenders.

“[Police] were pulling the Indigenous men’s hair,” Sleydo’ (Molly Wickham), a wing chief of the Cas Yikh House of the Gidimt’en Clan, told Amnesty International. “They piled on two of the Indigenous men really hard … kicking them and punching them in the head.”

Land defenders said they were held in custody for four to five days prior to their bail hearing, and several interviewees told Amnesty International that Wet’suwet’en and other Indigenous land defenders were treated more severely than non-Indigenous detainees.

“Only the Indigenous were in shackles,” according to Chief Na’moks, who noted that members of the media — who were also detained — were only handcuffed while Indigenous people were “in shackles, in their underwear” and made to appear in front of a judge this way, he said.

‘I feel less safe now’

Some members of the Wet’suwet’en no longer feel safe on the Yintah (land), resulting in loss of connection to their ancestral territories and, consequently, their ancestors, negatively impacting cultural transmission to future generations, according to the report.

“I feel less safe now that [my daughter] plays outside knowing there’s a strange man across the river watching; that there are drones up in the sky,” Karla Tait, a Wet’suwet’en matriarch and a director of programming with the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre, told Amnesty International.

Besides the large-scale raids where land defenders reported experiencing harassment and intimidation, Amnesty International documented a pattern of ongoing intrusive and aggressive surveillance, including discriminatory, degrading and highly culturally insensitive conduct.

Further, multiple people from Wet’suwet’en reported being followed by police and CGL’s private security, surveilled, harassed, and racially profiled.

One matriarch told Amnesty International about being subjected to “two police stops in one day while on the highway under the pretext of sobriety checks,” while others reported being photographed, filmed by drones and followed.

RCMP officers repeatedly interrupted cultural activities at the Gidimt’en Checkpoint, according to the report, including a ceremony mourning a community member’s death — despite repeated explanations of what was happening and requests not to enter.

Amnesty International asked the RCMP to respond to these various claims but told the group it “would be improper to comment,” according to the report. The RCMP also told Amnesty International that it “continues to support and participate in the investigations by the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP (CRCC) with respect to the allegations made against our members during the enforcement of various [B.C.] Supreme Court Injunctions.”

Sleydo’ thanked Amnesty International for revealing the depths of the police violence that has occurred against Wet’suwet’en people. She further said the report is “a warning call” to others.

“Private industry and governments … should not have their own private security and police force harassing and intimidating Indigenous people, Indigenous families and children on their own lands,” she said.

“If we allow this to continue to happen, this will set the precedent for all future projects in this country in this province.”

Meanwhile, Hereditary Chief Woos (Frank Alec) spoke of the consultation process with CGL and how the company undermined Wet’suwet’en house chiefs as it pushed to obtain environmental approvals for its pipeline.

The report details testimony from Wet’suwet’en members about how “corrupt” the consultation process was, with one saying that CGL would “have big, massive door prizes, like big TVs” every time they came to the community to entice people to go to their events.

Amnesty International also heard that neither CGL nor the province considered recommendations made by hereditary chiefs throughout the consultation process.

“CGL, B.C. and Canada undermined the house chiefs,” said Chief Woos.

“They forced this project into Wet’suwet’en lands.”

Amnesty International asked CGL about the agreements and alleged divisions created within the community. Representatives told them their work “is lawful, authorized, fully permitted and has the unprecedented support of local and Indigenous communities and agreements in place with all 20 elected First Nation councils across the 670 km route.”

The company also wrote a letter stating that “we respectfully disagree with many of the draft findings.”

However, the report concludes that CGL “failed to obtain the free, prior and informed consent of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs for the CGL pipeline project” and calls on the company to halt operations in the territory and for the provincial and federal governments to rescind any permits for the pipeline. According to CGL, the pipeline is now in the final stages of construction.

‘This report is telling the truth’

To conclude their report, Amnesty International made a laundry list of recommendations to the main parties involved: the provincial and federal governments, the RCMP and C-IRG, CGL and TC Energy, the privately-contracted Forsythe Security and the international community generally.

However, Nivyabandi said what they’ve heard back so far isn’t very comprehensive.

“In the process of putting this report together, we did reach out to various government officials, to all the parties listed in the report, including Coastal GasLink,” she said.

“Unfortunately, what we have heard does not begin to answer or address the recommendations we have made in full.”

Chief Na’moks said, for him, the report lets the world clearly know what’s happened to his community.

“It is letting the world know to question the narrative,” he said.

“Do I think it’ll make a difference? That is up to the elected officials, but you know what, you’re the ones who elect them. They’re supposed to listen to you. We’re telling the truth, that’s what we’re doing, and this report is telling the truth.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

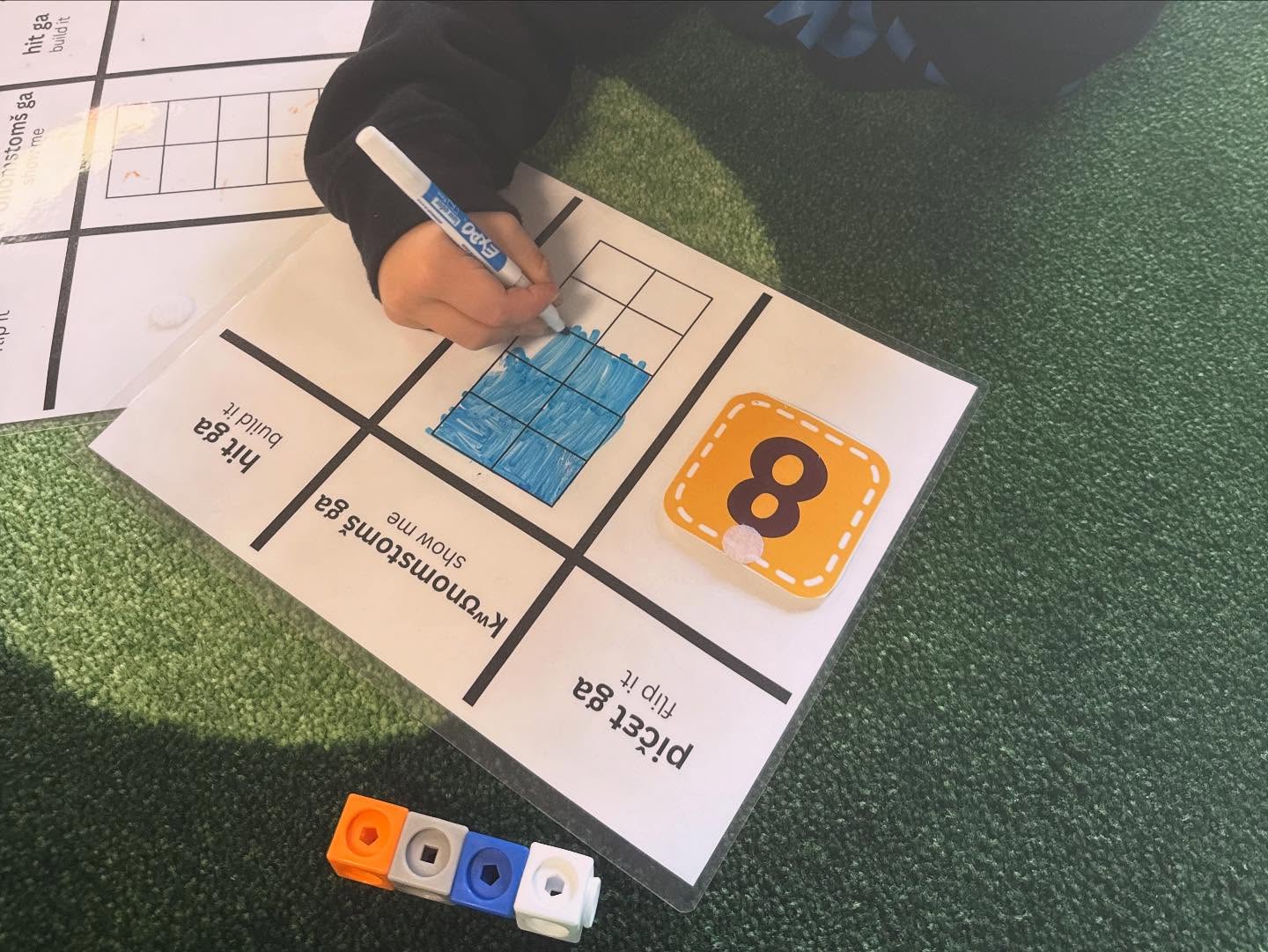

‘Witnessing our ancestors’ wildest dreams’: Tla’amin children immerse themselves in ʔayʔaǰuθəm

At the nation, a preschool to Grade One classroom is taught only in ʔayʔaǰuθəm— allowing young children to connect to their ancestral language