Ocean’s ebb and flow becomes ‘grounding force’ behind new exhibition

Vancouver Art Gallery’s ‘We who have known tides’ brings together nearly 40 pieces that reflect how Indigenous people have been shaped by their coastal territories

Nestled among an expansive collection of contemporary Pacific coastal artworks, a looping two-minute video by Nicholas Galanin radiates a quiet joy that reaches across the Vancouver Art Gallery.

The Lingít (Tlingit) and Unangax̂ artist’s film — k’idéin yéi jeené (You’re doing such a good job) — is a simple, profoundly human anchor within the new exhibition We who have known tides.

The five-room display gathers work from twenty Indigenous artists — with each exploring their relationship with the ocean and offering powerful visual expressions of respect for the sea and its beings.

On screen, Galanin’s young son looks towards him, then out to sea on Lingít territory, as his father speaks soft words of affirmation in Lingít.

With each phrase, the boy’s face shifts, often blooming with delight. Hearing the language, seeing the words, and watching his expressions invites visitors to experience a tenderness that moves through you and settles deep in the body.

“I hate to show bias, but it’s one of my favourite things I’ve seen in a long time,” said curator Camille Georgeson-Usher.

“You just see the reaction and the joy and this loving nature that Nicholas has with his son.”

It’s a disarming way to enter this section of the exhibition, and exactly as Georgeson-Usher intended, she said. Then, visitors are drawn toward a dramatic centrepiece of undersea masks — an early signal of the emotional tide she wants visitors to feel as they move through the displays.

Ocean flows became exhibition’s ‘grounding force’

We who have known tides — which opened November 6 and runs until April 12 — is Georgeson-Usher’s inaugural exhibition as the gallery’s newly appointed Audain Senior Curatorial Advisor on Indigenous Art.

She is Coast Salish from her grandfather’s side, and Dene through her grandmother from “Fort Good Hope” in the “Northwest Territories,” but has spent much of the last 15 years away from her Coast Salish home territory.

Living in “Montreal” and “Toronto,” she would find herself running toward any body of water she could reach.

“I’d go to lakes and rivers trying to remember the ocean,” she said. “But obviously it’s not the same.”

Instead of trying to replace those memories, she wrote poetry “in memory of the ocean,” which she offers as gentle prompts throughout the exhibition.

But the prompts aren’t instructions, she noted.

“They’re suggestions,” she explained, “of a feeling that I’m hoping you’ll get in the space.”

This longing for home waters became Georgeson-Usher’s anchor as she sifted through the gallery’s expansive collection of Indigenous contemporary art.

“I had too much to choose from,” she said with a smile.

The ocean, and the concept of tides — not merely literal, but also political, personal, and social — became her way of shaping the exhibition’s narrative.

“The ocean really became the kind of grounding force,” she recalled. “The idea of tides is this kind of ever-flowing ebb, in and out … all these things come and go.

“I wanted us to feel that push and pull, that flow of a wave.”

Her two-year position, which she began in May, is an endowed position funded by the Audain Foundation. It is the first role of its kind at the gallery, located on xʷməθkʷəy’em (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh, and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) territories.

Georgeson-Usher, an established art historian at the University of British Columbia, said it was important the exhibition’s curator “be from here,” because whoever fills the role should be grounded in relationships and responsibilities within local lands and communities.

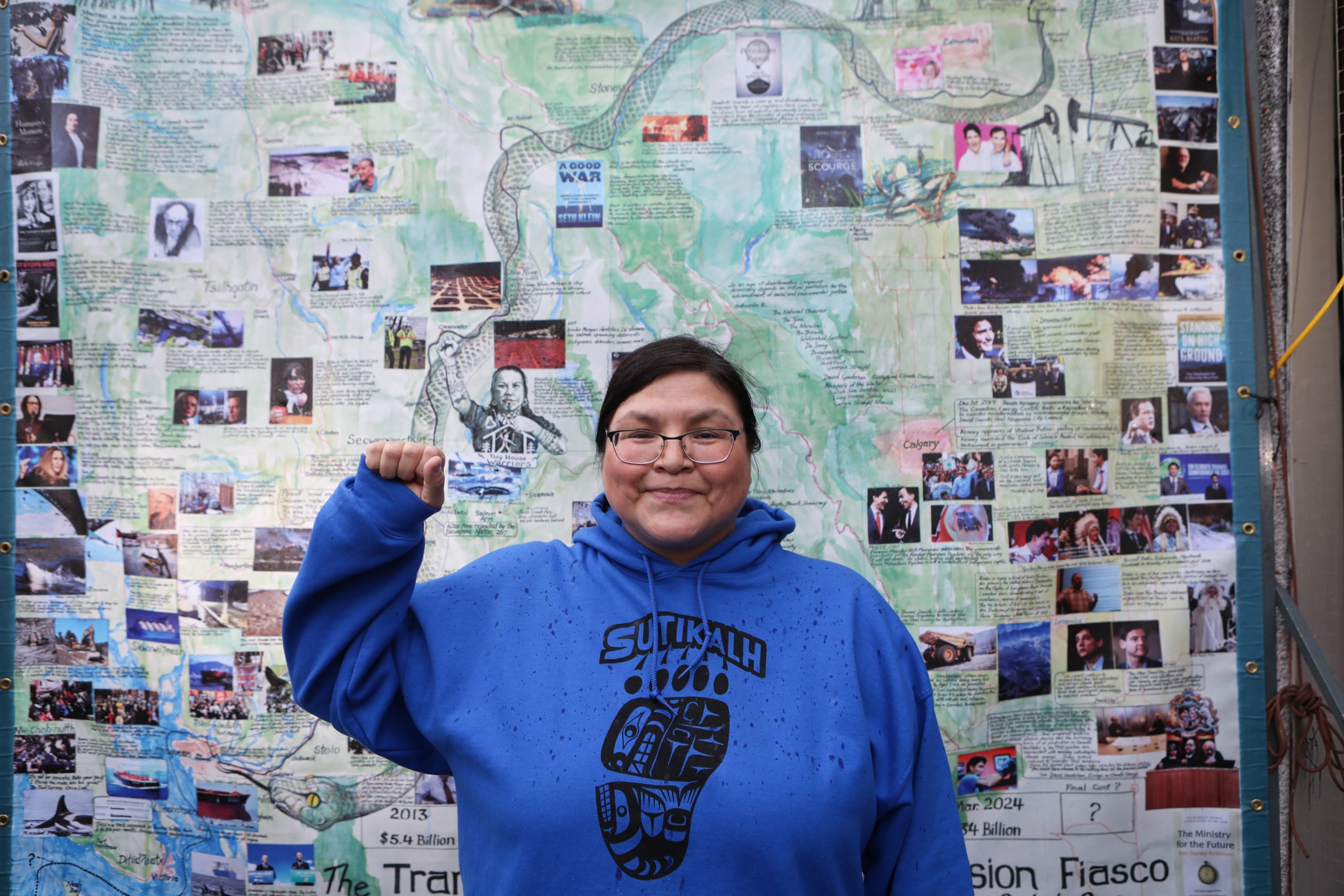

Through this lens, she began weaving together works by artists who represent living lineages of artmaking on the Pacific coast. They include Qwasen (Debra Sparrow), Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, Susan Point, Skwetsimeltxw (Willard “Buddy” Joseph), and Walas Gwa’yam (Chief Beau Dick).

A ‘lull in the tide’ — and a living current

Entering We who have known tides from the gallery’s spiraling rotunda stairwell, visitors encounter the exhibition’s title — a newly commissioned, brightly coloured text-based work by Haida and Québécois artist Raymond Boisjoly, stretched across an ice-dyed canvas.

Using a dyeing method that resists control, Boisjoly’s canvas becomes a shifting surface of colour and texture, with patterns resembling tree stumps.

“You can’t really predict what the piece is going to look like,” Georgeson-Usher said. As she sees it, the sprawling canvas’s lively neon words and patterned dyes interact to challenge viewers’ expectations about language and legibility.

The next room, which she described as a “lull in the tide,” shows artworks intended to bring a sense of peace.

At its entrance is a coat by xʷməθkʷəy̓əm Elder-in-Residence Skwetsimeltxw (Willard “Buddy” Joseph), a leading figure in the revitalization of Salish weaving.

“I love the drama of it — the tassels, the texture,” she said. “I absolutely fell in love with this coat.”

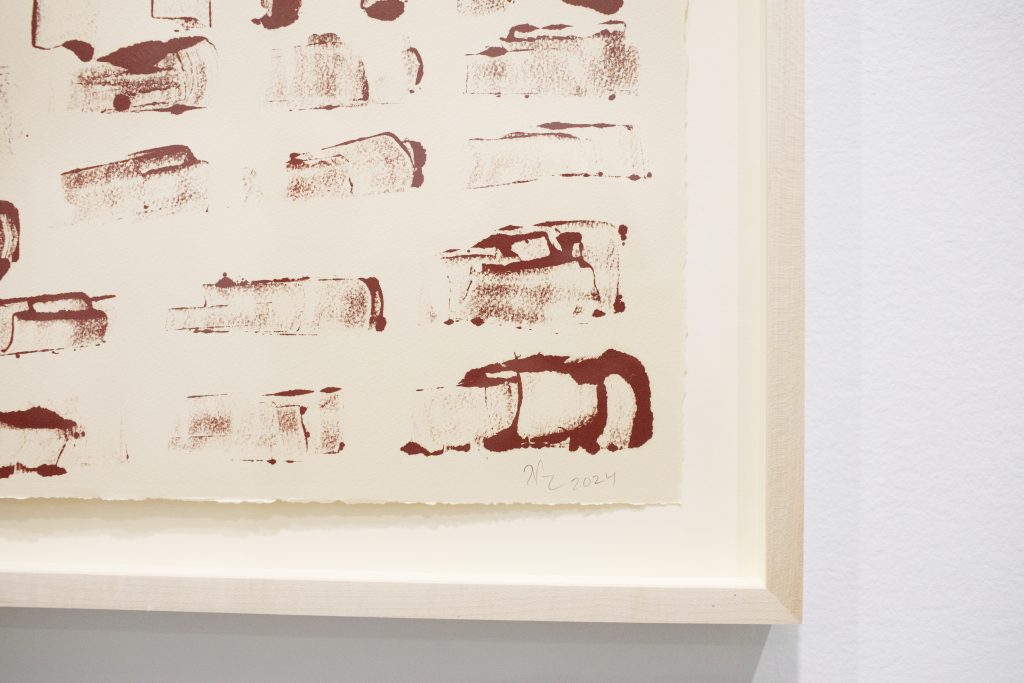

Nearby sit two works by renowned xʷməθkʷəy̓əm artist Susan Point, one a print and the other a carving; the room also features two monotype prints by Galanin, created by rolling cuts of salmon in paint and printing them onto paper.

Sent from the Peter Blum Gallery in “New York City,” the salmon prints were the only pieces shipped to the gallery

At what feels like the exhibition’s centre, the late Walas Gwa’yam’s (Chief Beau Dick’s) Undersea Kingdom showcases a collection of his carved masks, coursing through a long room as if in a sweeping procession, its arc suggesting a living current.

Each of Walas Gwa’yam’s 17 masks in the room is intended to be worn, Georgeson-Usher reminds visitors.

Traditionally, such masks would be danced in a circle, but the gallery’s architecture made this impossible to recreate. Instead, she displayed them in a flowing line — “a gesture toward the circle,” she said.

Some of the renowned carver’s masks are expressive, others unsettling. But all seem to carry a sense of movement and energy, despite being fixed on display in the space.

In Walas Gwa’yam’s Kwakwaka’wakw tradition, masks are performed four times before being ceremonially burned.

“Their lives end,” explained Georgeson-Usher.

Walas Gwa’yam fulfilled this tradition in 2012, when he took 40 masks from his own gallery in “Vancouver” back to his community and ceremonially burned them.

“These ones haven’t been used yet, but they could be,” she said. “That’s what they’re for.”

Turning the gaze upon galleries and museums themselves

One of We who have known tides final rooms brings together works that question what a museum or gallery “collection” even is — and what it’s for.

Drawn entirely from the gallery’s own vault, the exhibition’s focus turns inward, inviting visitors to consider how objects are held, stored, and brought into relation with one another.

Here, Kwakwaka’wakw artist Sonny Assu gathers cedar offcuts left over from log-home developers in his territory. Each fragment bears the scars of a mass-produced economy, while also echoing the shapes of traditional masks. In doing so, each carries an ancestral connection, said Georgeson-Usher, despite its altered form.

Nearby in the gallery are two wall hangings woven by Qwasen (Debra Sparrow), a celebrated and prolific xʷməθkʷəy̓əm weaver.

Her decades of work have been central to revitalizing Coast Salish weaving traditions, helping reconnect her community with its ancestral textiles, and ensuring that cultural knowledge continues being transmitted.

Across the room, a three-channel video installation by Sugpiaq artist Tanya Lukin Linklater — which made its debut in We who have known tides — expands the exhibition’s conversation further by scrutinizing Indigenous collections more broadly.

Her contribution, Quiver, explores Indigenous relationships to ancestral belongings held in institutions like museums and galleries.

The video installation explores the tensions underlying such collections.

She emphasizes a stark contrast: the ease felt by three Youth enjoying the simplicity of being on the land, against the effort required when entering an institutional space just to view belongings stolen from one’s ancestors.

For visitors standing inside a gallery’s own collection while watching a video of Indigenous people visiting stolen objects in a collection, Lukin Linklater’s work takes on an added resonance, Georgeson-Usher observed.

Through the video installation, viewers understand why it’s important for Indigenous people to visit their ancestors’ belongings, “which feel lonely as we watch the portrait of the collection space where they just sit, alone, in silence,” she explained.

But as we transition to the installation’s footage of the three Indigenous Youth, relaxing near the shores, “it feels luxurious how they are simply just being.”

The act of visiting the ocean, she said, becomes a “method of regeneration,” as the Youth spend time in the collections, with important belongings, with each other.

“Tanya is insisting upon a form of community and relationality in these spaces,” Georgeson-Usher said, “where it hasn’t felt previously allowed.”

Editor’s note: This is a corrected story. A previous version said prints by Nicholas Galanin were from his own collection. In fact they were from a gallery. A previous version also said there were nine artists in the show — in fact there are 20. We apologize for the error.

Author

Latest Stories

-

Inquest continues into Winnipeg police shooting death of Eishia Hudson, 16

Non-adversarial probe of teen’s death cannot assign blame, but family and First Nations hope it will recommend meaningful ways to prevent similar police shootings