Indigenous cradleboard keepers are revitalizing traditional parenting practices

Found across many cultures, the baby carriers are a tangible connection to ancestors, explains Anishinaabe writer Joleen Banning

As I walk down the hallway of the Nor’Wester Hotel and Conference Centre in Thunder Bay, the first room I encounter catches my eye.

There are bright colours and objects I recognize: cradleboards, or tikinagan as they’re known in Anishinaabemowin, of all different shapes, sizes, and materials.

I am struck with wonder looking at the cradleboards made of etched wiigwaas (birch bark) with old pictograph images; fully beaded moss bags; embroidered bags; baby carriers adorned with quills, shells, beads; and an amauti, a coat used by the Inuit.

Some carriers are woven together, while others are solid pieces of wood. Each one tells a different story — but every layer set to be wrapped around a baby is endowed with love, and protection, and belonging.

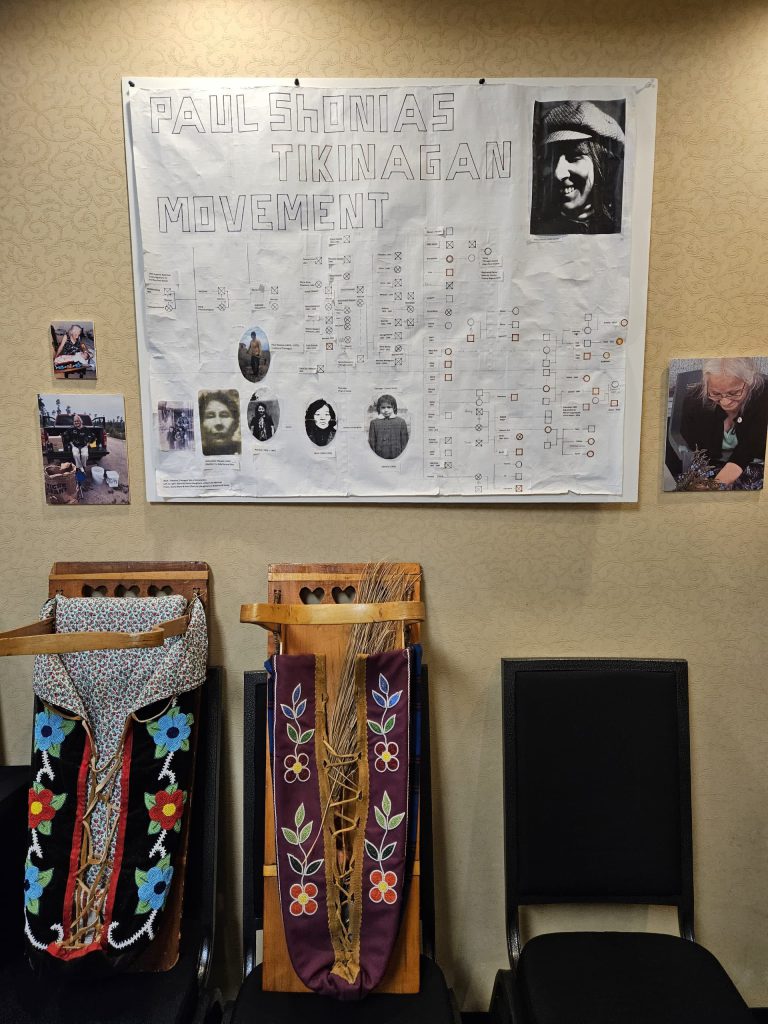

One tikinagan is on a table next to a photo of Patti Nawagesic and an older black and white photograph labeled “Paul Shonias, tikinagan builder.”

Both names are familiar to me.

Then I spot my former college professor, Shirley Stevens. We were both invited to the same event hosted by Anishinabek Nation about Indian Residential School research and methodologies.

I ask her about the collection of cradleboards, and how she’s managed to obtain such a collection.

Stevens has amassed a collection of more than 250 cradleboards, from Nunavut to South America, across the continent, and she has set them up geographically by region. A passion first fueled in an attempt at finding her daughter’s tikinagan, that was lost during a move in 2011

The cradleboard exhibition — Dakobinaawaswaan (Baby in a Cradleboard) — was organized by Stevens and her group the Cradle Keepers Collective, eight Indigenous women whose goal is to educate and revitalize these important cultural items.

But when Stevens started collecting cradleboards nearly a decade ago, it was without much thought about what she would ultimately do with them.

By displaying the cradleboards, the Cradle Keepers Collective want to remind not only Indigenous people, but all Canadians, of how important our children are, to see the beauty of our family life — that we were and still are good mothers.

“I felt really strongly that it was so important to have people in communities, see something within their living memory. So it’s not so far gone that people can’t remember,” Stevens tells me.

“Because there are still people using them. I really wanted people to recognize that they’re still really important, they’re so symbolic of all kinds of things.”

People have seen the exhibition, heard Steven’s message, and are taking action to continue the education and building of baby carriers such as Anishinaabe artists Shannon and Ryan Gustafson.

The couple are sought out throughout North America offering courses to build your own tikinagan. They share their personal story of using one, traditional teachings and nearly someone in every group has a story to share of knowing someone in their family that builds them or being raised in one themselves.

The Gustafsons are helping us to remember our original core family values, to give our children the best start in life, to give us something to strive for, to remember who we are.

Layers of love and protection

The exhibition was back in October; I’ve since been invited to become a member of the Cradle Keepers Collective and have witnessed the power of belonging, female friendships, kinship, and learned more about these sacred items.

Before seeing the exhibit, I couldn’t see my own connection clearly. But as I take a look around at all the cradles, I can’t help but think of my own complicated and unique personal history.

Although I’ve always known who my father was — Paul Myles Pervais — I didn’t actually meet him until the early 2000s when we both attended a local college at the same time. During that time at college, my placement supervisor for the term was Nawagesic, who also taught me how to bead using two needles.

My paternal grandfather was also like me — he didn’t know all of his family at a young age. My dad tells me my grandfather was only 10 years old when his mother left her reserve of Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek (Gull Bay First Nation) and moved to Fort William First Nation.

He never knew all of her family — but knew his uncle Paul Shonias. He later learned from a local community historian, his nephew, that his mother had 14 other siblings.

My grandfather grew up believing he only had one uncle and named my dad after him: Paul. And now I know that is the same Paul Shonias who made the tikinagan for all the babies within his family, chronicled by Nawagesic.

What I’ve grown to realize is that we are all connected and interconnected with so much love and prayer — and the tikinagan is the best representation of exactly that.

The tikinagan is a great representation of our world values, that spans across all Indigenous nations around Turtle Island, or North America. In our worldviews as Anishinaabe people, we pray for the seven generations to come while also knowing that we have been prayed for by the seven generations before us. These cradleboards are a tangible connection to our ancestors who guide us.

In Anishinaabe values, as in many Indigenous values, the baby is the most important being to join a family.

The baby holds a strong connection to the Spirit World and Creator. So the family wraps them up tightly — in their cradleboard adorned with beautiful images of protectors and helpers beaded onto the fabric, or carved onto the wood, or etched in the birch bark — to show the love and belonging the baby has within the family unit.

‘A resurgence of our old ways’

One member of the Cradle Keepers Collective is Elder Marlene Pierre. All her children were reared in a tikinagan. She says not only do these baby carriers show beauty and craftsmanship but they also capture how the child will be raised.

“You can see today the historical impact of the government and church breaking up our cultural and traditional way of life and replacing it with something that wasn’t ours, and trying to destroy our spirituality almost to extinction, but this exhibit shows that was not us,” she says.

“This exhibit is a resurgence of our old ways.”

From the start, the baby is wrapped in layers upon layers of love and protection from immediate to extended family and community.

When tribal groups made a treaty or peace with each other, the cradleboard was often given as a gift because it symbolizes and it recognizes the importance of children and the generations to come, the interconnectedness of it all, explains Stevens.

Kimberly Murray, the Independent Special Interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites associated with residential “schools,” was also among the invited guests at the Nor’Wester Hotel.

The Interlocutor’s report contains the work done over a two-year period. Within that time there were national gatherings, meetings with survivors, knowledge holders, Elders, families and communities, searching records of residential “schools” and other institutions.

Her findings of children that died while in residential “schools,” or Indian hospitals or asylums, were not missing children at all but rather victims of “enforced disappearance” because they were made to disappear by the state. All information obtained is available for the public to read yet denialists continue to disregard the truth and spread false narratives that there are no unmarked graves.

After Murray saw the exhibition of cradleboards in Thunder Bay back in October, she invited the collective to attend the release of her final report on the Missing and Disappeared Indigenous Children and Unmarked Burials in Canada and asked that we bring the cradleboards to Gatineau, Quebec.

Everyone at the table immediately said yes and got to work.

One member of the Cradle Board Keepers was calling different transportation moving companies, another was calling about flights and train tickets, while another was getting everything into a spreadsheet to create the budget. I volunteer my time and offered to drive.

The women in the Cradle Keepers have been friends, and interconnected in each other’s lives, for the last five decades.

One family in the collective were part of the Indian Homemakers’ Association, doing advocacy work that led to the creation of late night talks in the early days of the Thunder Bay Indian Friendship Centre; those discussions, in turn, led to the creation of the Ontario Native Women’s Association, which led to groundbreaking reports on violence against women, upheld by colonial law.

There are family connections now as these young women, neechees (meaning friends in Anishinaabemowin) grew and evolved into powerful women. When Stevens started collecting her cradleboards, her best friend, Nawagesic, watched on and got curious about her own family tikinagan and the history behind it.

She started thinking about how many babies had their start in life in her family cradleboard and did her own family genogram. A diagram of all her family members, extended family members, dating back. The family genogram demonstrated how the cradleboard was constructed by her uncle Paul Shonias of Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek, and passed down through the women who raised their children in the cradleboard.

What she was able to show was the cradleboard being moved amongst a lot of children. Roughly 27 children have started off in the family cradleboard made by her uncle Paul.

In her final report, Murray’s message was loud and clear; that is just the beginning. We need Indigenous-led searches, protection for burial sites and justice and peace for families. Many families were often not told when a family member had died or when or where they were buried. The report is horrific.

It pains me — especially as a kokum of two young grandchildren, with a third on the way — to read that the federal government has allowed vulnerable, young children to experience acts of violence, starvation, neglect and other atrocities.

Stevens says they couldn’t turn down the invitation and sees the cradleboards offering a comfort, a soothing balm on an open wound, that they somehow temper the horror of children’s unmarked graves at residential “schools” — reminding them of their start in life with family, community, love and protection. Elder Pierre agrees with the sentiments of the energy the cradles offer, but is also looking ahead to the possibilities for Anishinabek people.

“I’m focused on getting our own people to see the beauty of our family life and that we weren’t terrible parents,” she says.

She says Anishinaabe were misjudged by a colonial system with laws to support further breaking of family units and community.

“It was the government, police, social workers, imposing their value system on us,” she said, “and that allowed them to take our kids and put them into Indian residential schools, undertake the 60s Scoop, and force us into their child welfare system.”

Indigenous ingenuity

Karen Peterson, a lifelong friend and ally to the Cradle Keepers Collective, speaks of how the cradleboards are a reminder of Indigenous family structures.

“The cradles are an eye opener for a lot of people because they haven’t been exposed to that type of connection to community and people,” she says.

“It’s changing the narrative in a subtle way.”

The cradleboard is a prime example of Indigenous ingenuity and unparalleled knowledge because the boards did more than simply hold a baby. Sure there is the artistic aspect of making it — adding beauty and culture — but it provided so much more.

“The board was meant for protection. If the cradle fell over, the child would be protected. You could also protect them from the sun,” says collective member Beverly Sabourin.

“You could hang a blanket over the cradle, and make it dark for them to sleep. The wrapping makes them feel warm and comforting.”

While immersed in this project, Sabourin says she reached out to family on social media, and learned her own grandmother had made a cradleboard for each of her grandchildren.

“Those cradles represent that very rich cultural aspect of parenting, showing how Indigenous people parented, and the disruption that occurred with residential schools and all these missing children,” she says.

“I think all those cradles are now helping tell that story. These are rich, spiritual human beings coming to help restore those lost children.”

Patience, tolerance, protection

Peggy Smith, member of the Cradle Keepers Collective, was raised in a Roman Catholic family, with the parenting belief of “spare the rod and spoil the child,” she explains. But the cradleboards give her an alternative vision of child rearing.

“That’s the message that comes through all the time for me. Is how we treat our children. Everybody has something to learn from that,” says Smith.

“Treating children in a better way and giving some respect back to Indigenous ways of child-rearing.”

Her sister had children with a man from Sandy Lake First Nation and she watched how he raised her niece and nephew. He takes his time to teach them, to talk to them, which is something completely different from what she experienced growing up.

Patience, tolerance, protection and learning by observing are all cradleboard teachings.

“I’d like to see those cradleboard teachings spread loud and clear over a long period of time. It’s a message worth hearing and a message worth delivering.”

I spent the earlier part of my life trying so hard to fit into colonial systems. Going to public schools that aim to assimilate, buying all the brand name clothing and jewelry, only to learn, I don’t need to fit into a world that isn’t mine.

The story of the cradleboard, the tikinagan, the moss bag all have the same agenda; to bring us together, united with love, protection, culture and beauty. They let us know we belong.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Truth, courage, care’: Esk’etemc leader honoured with ‘B.C.’ reconciliation award

Charlene Belleau has been ‘leading voice’ of justice for survivors — documenting truth and supporting community healing

-

Across the border, Indigenous fears spike amidst ‘U.S.’ immigration crackdown

With ICE operations, multiple First Nations warn members about travel risks — despite treaty rights. Why Indigenous communities are on the frontlines defending rights for all