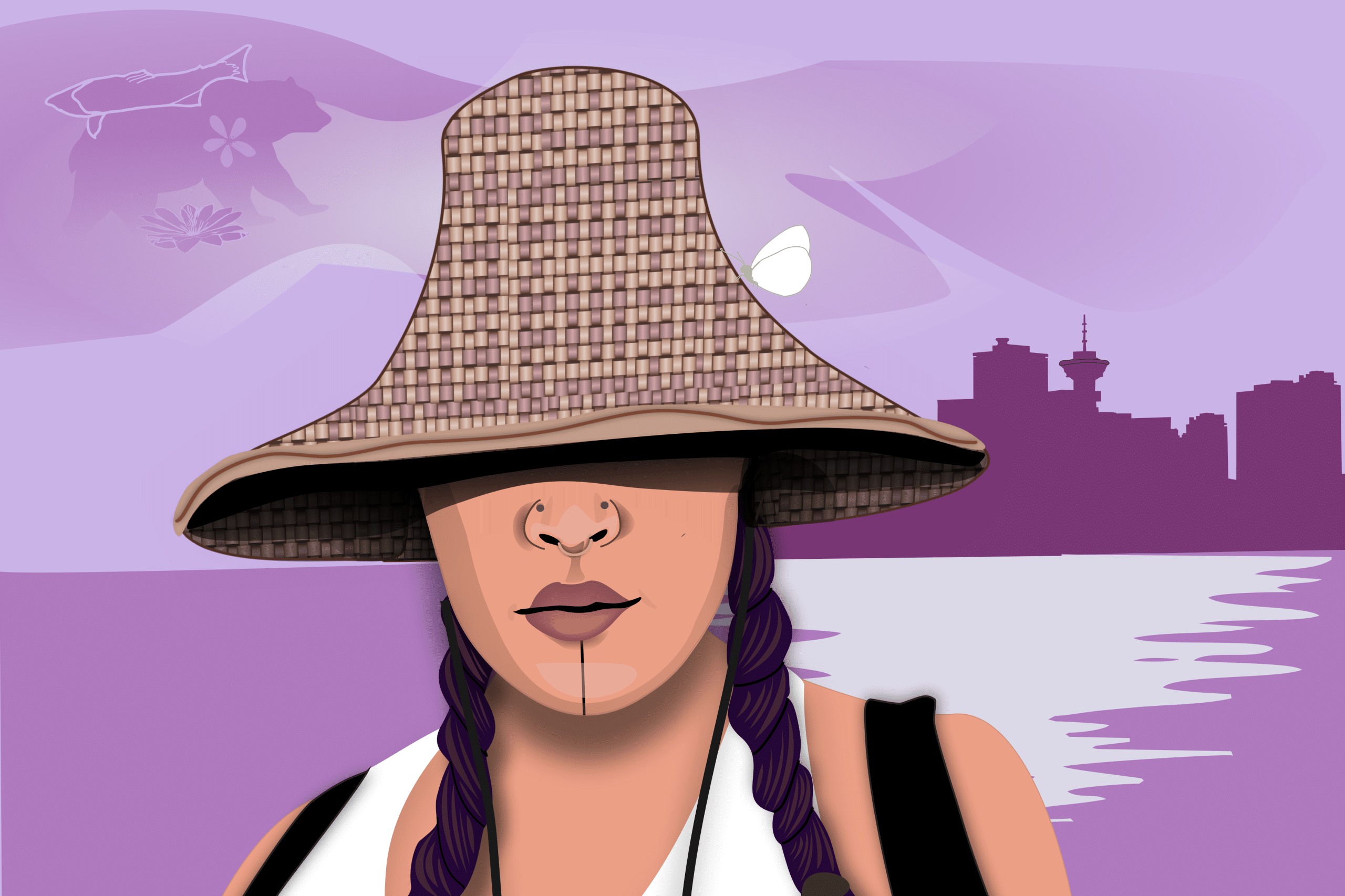

The search for Kwemcxenalqs

After losing their beloved relation, the family wants VPD to come to syilx homelands to apologize for a lack of sensitivity

This is the second story in a two-part series. The first part, a tribute to Kwencxenalqs, can be viewed here.

Editor’s note: This story was written in consultation with Juanita Lindley and family with respect for grieving protocols. In accordance with this, we respectfully ask other media to refrain from extracting from this story in any way. IndigiNews cites UNDRIP article 31 which upholds our right to control and protect our stories and histories.

Content warning: This story involves content regarding Canada’s ongoing genocidal epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two Spirit and gender-diverse. Please take care of your spirit and read with care.

It was a warm summer night on the homelands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and səlil̓wətaʔɬ, and people were beginning to pour onto the beaches to take in the Celebration of Light in what has been briefly known as “Vancouver.”

Seventeen family members of Kwemcxenalqs Manuel-Gottfriedson had split up on foot to the parks, streets and beaches — searching for their beloved who was reported missing two days earlier.

As exhaustion overtook them, her mother, aunties and sister came upon a group of officers from the Vancouver Police Department (VPD) and asked for help. But instead of receiving assistance and care, the family says they were completely ignored — “confronted by the hard reality of the invisibility Indigenous lives often take,” a family statement says.

As the evening went on and the family was in immense crisis — they say the police demonstrated a lack of cultural safety and trauma-informed care towards them. The family, which has a swell of community support behind them, has now released a series of recommendations aimed at the police, media and the coroner’s service.

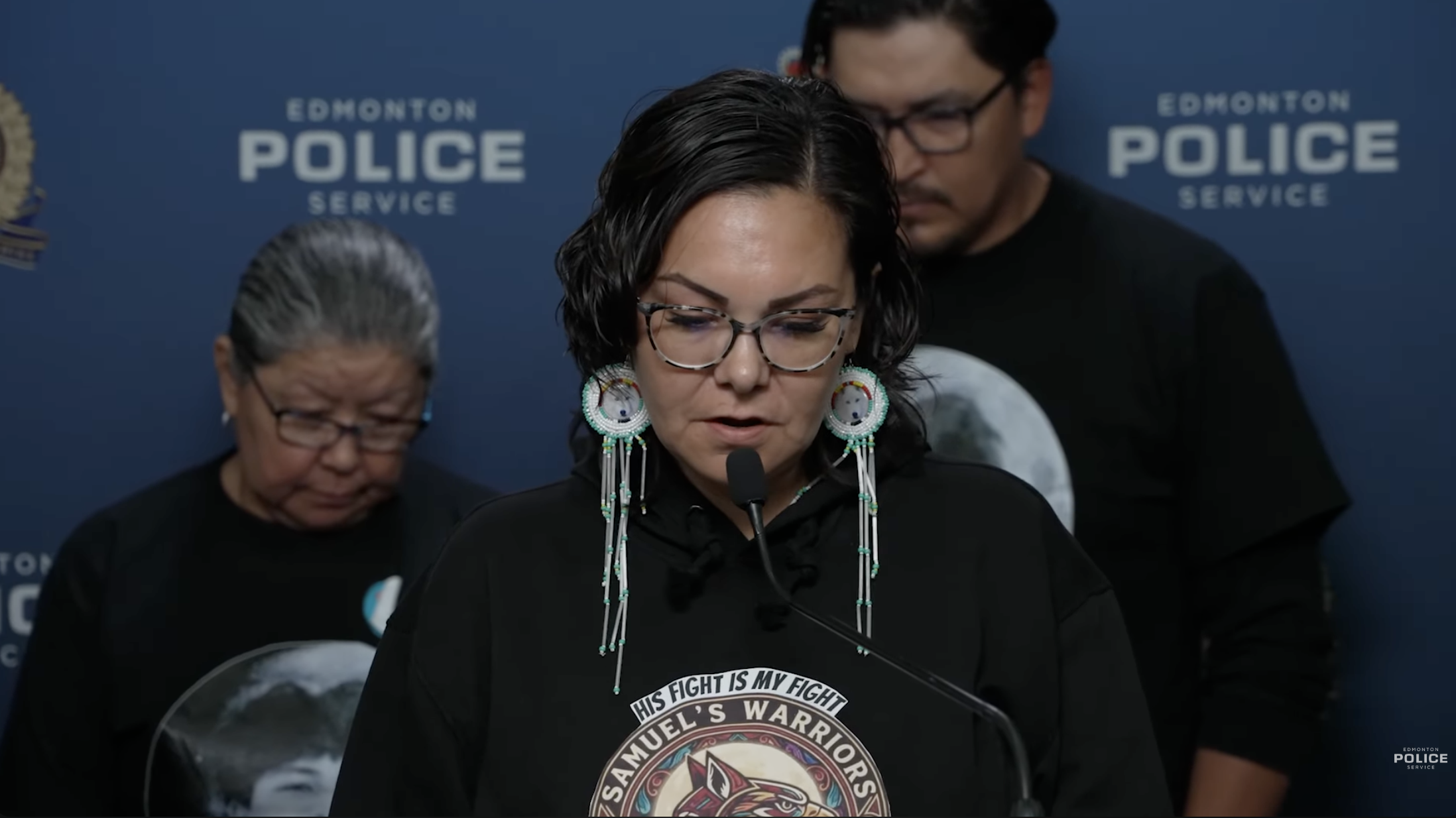

“This is our pathway forward,” Juanita Lindley, mother of Kwemcxenalqs, says with a warm but strong voice.

“To me, experiencing it and making the recommendations was a part of prayers, prayers for the people who are also going through this, who will go through this, or who have gone through this.”

The family’s recommendations echo those that have come up previously — specifically in the MMIWG inquiry final report — but with renewed urgency after families like theirs continue to be failed by colonial systems. They are also asking for an apology.

“VPD needs to come to syilx territory and apologize to us on our homelands,” Juanita says.

Daniel Manuel, Uncle of Juanita and Kwemcxenalqs, shares that having the VPD come to syilx homelands is so they can move their grief ceremony forward and receive an acknowledgement of the harms that were caused.

“All we want is simple recognition of who we are, that our ceremonies are valid and important,” he says.

“Now that everything is done we have to look after our feelings, and do it in a culturally appropriate way because we don’t want anybody else to be hurt. And our cultural practice is to deal with that in ceremony.”

The search

The family says the systemic mismanagement around their case began at the very start of their search and continued far after receiving the news that she had started her journey to the Spirit World.

Because Kwemcxenalqs was living in “Coquitlam,” it took a couple of days for her family in her syilx homelands to find out she was missing. It was Friday, July 29, and Juanita and her daughter Nexpetko were getting ready to go to the Kamloopa Powwow.

While sitting outside of a small cafe on the unceded homelands of the syilx and Nlaka’pamux peoples in “Merritt, B.C.,” they received news that Kwemcxenalqs, 25, hadn’t been in contact with anyone since that Wednesday. After meeting with the rest of the family and confirming police had been informed, they made their way to the coast to begin the search.

“I started making plans because I was like, ‘Alright, I’m gonna go down to the city, and we’re gonna have to go and look for her,’” Nexpetko shares.

By the time they made it to “Vancouver” it was already very late at night, heading into the wee hours of the morning. They searched around “Stanley Park” until around 4:00 a.m. before they headed back to a family friend’s home in xʷməθkʷəy̓əm.

The next morning the family woke up, printed posters and started their search once again. By this time it was Saturday, July 30, and every moment that passed felt agonizing while they frantically made phone calls, scouring streets, parks and beaches, seeing if anyone heard anything from her.

In “Vancouver” that weekend was both the firework festival Celebration of Light as well as Pride. With the city bustling with people, the family split into four search groups.

“We didn’t even know where to start looking, so we went to Hastings first and we bought cigarettes to hand out to people so that they would know who we are, and that we’re not coming in a malicious way,” Nexpetko says.

From there, the family moved from “East Hastings” to “English Bay,” hanging posters where they could. Eventually, they moved up to “Second Beach,” and after hours of walking and searching in the heat of the summer, running low on energy, Nexpetko shares that’s when she had a sinking feeling.

“[Kwemcxenalqs] had been missing since Wednesday. So it had already been two days since she was gone. And by this point, I just thought she would have already called,” she says.

“It’s almost the end of the day, and we’ve already walked around so much. No one’s recognizing her so there was this powerlessness. Like no one wanted to help.”

Nearby, VPD officers were filing out of a police van. Nextpeko’s aunties told her to go and give the officers one of the missing posters they had made. She ran to them with a large printed poster of her sister in hand and began raising her voice so they could all hear her. She recalls she said “excuse me” several times, and the police kept walking by as if she wasn’t there.

“It was obvious they were ignoring me, they acted like they didn’t see me, not even acknowledging me. But they saw that I was standing there — holding a missing poster,” Nexpetko begins to tear up but continues to share.

As the officers — some smiling, some talking to each other — continued to walk by blankly, Nexpetko felt her spirit break.

“I was already looking for my sister all day,” she says. “And you know, you think, or you’re told, that the police are supposed to help. And I just thought they would at least acknowledge me.”

‘What I just witnessed’

Juanita saw her daughter turn around, and she had tears streaming down her face.

“I just hollered for her, ‘come here,’ and she came running to my arms,” Juanita shares.

“I remember thinking to myself, I can’t let my baby see me walk by the VPD without saying anything. I have to do something to fix this.”

With each step full of purpose, Juanita walked towards the VPD — now, with dozens of officers on site standing in different groups. She addressed the officers in nsyilxcen when she put forward her sqilx’w skwist (Indigenous name), “xas cənitkʷ,” and began to command their attention by looking them each in the eye.

With unyielding love for her children she told the officers that ignoring her family was racist and called them out for lack of cultural safety.

“From what I understand is that the VPD are supposed to be in good relation, in good standing, and building relationships with Indigenous people who are experiencing this,” she recalls saying. “But, what I witnessed you do is shameful.”

As Juanita shared this to each group, Nexpetko followed behind her mother and handed a flyer to every officer there.

Across town

While this was happening at “Second Beach,” across town on “East Hastings” Roipellst, Kwemcxenalqs’s brother, was also asking the VPD for help after finding out from people in the area that his sister was last seen at the Woodbine building.

In the hotel, he showed the police the missing poster, he says, and was told that investigators were working on the case but they couldn’t say anything about it.

“Then I said, ‘Okay, well, if you can’t tell me anything about it, is there anything you can do to help? Or is there anything you know about [finding missing people] that could help me maybe find her?’” he shares.

“And he said, ‘No, just leave it alone.’”

Frustrated, Roipellst looked over at one of the nearby officers and felt a moment of connection — she told him to pass on his name and phone number.

“I just sort of knew because the looks on their faces and the way that they handled the situation I knew that it was my sister in the apartment that I was standing outside of,” he shares.

“I just stopped searching after that because I already knew what had happened. And I didn’t tell anybody about it because I didn’t want to make anybody else worried that I found out, that I came so close to her,” he says with a calm and steady voice.

“Later that night it was confirmed.”

The responsibility of being Indigenous

The family says that when they were informed that Kwemcxenalqs had passed on, there was also a lack of cultural care that worsened an already-traumatic experience — and that lack of sensitivity continued as they began following sqilx’w grieving protocol.

Daniel and his wife went to “Vancouver” to take part in the ceremony work that needed to happen when Kwemxcenalqs passed onto the Spirit Realm. He shares that the process of moving through their sqilx’w grieving ceremony was interfered with by the VPD and the BC Coroners Service. Both placed their policy and process as more important.

“The death ceremony, we put our loved ones who passed away in high regard as soon as we receive that news. We don’t wait. Their process is still disrupting our ceremony,” he says.

“We have so far to go with Truth and Reconciliation, we have barely scratched the surface. All we’ve done is put on orange shirts. But the deep roots of colonization are embedded in every bit of legislation and policy.”

Kukpi7 Judy Wilson, of Neskonlith Indian Band, and secretary-treasurer of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs (UBCIC), agrees with Daniel and says that the work has yet to happen. She finds strength coming from Indigenous people through her own personal experiences with Missing Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Two-Spirit, and gender diverse.

“Our lives are on the line. And police violence happens way too often. Any hesitation to implement the radical change amounts to the ongoing systemic racism. So when any Indigenous person is harmed by the police, we feel as a community the loss of a relative, and it is huge, it has huge impacts,” says Kukpi7 Judy.

“And, you know, not just the historical losses we have faced, but the loss over how our relatives are no longer in the community, the future losses over our young generation, and what they would contribute to the community.”

‘It’s their system; it’s not ours’

A family statement adds that the experience with the VPD is likely one faced by many families when searching for missing loved ones — which is why the family is demanding training for officers in cultural safety and trauma response.

“This event was not an example of the VPD being in good relations with Indigenous Peoples and was absent of even basic acknowledgement of our humanity,” the statement says.

“The City of Vancouver and VPD needs to invest in an Indigenous crisis response team so that there is cultural care integrated into every aspect of cases of MMIWG2S+. It is pertinent to have Indigenous people in these roles and working with our people.”

Juanita shares that the recommendations were created alongside her friends and family as a call to action to address the continued harms caused to Indigenous Peoples and families of the missing. She hopes to set a new standard going forward so other families don’t have to deal with the same thing.

“The current colonial processes and procedures in place are systemically harmful to Indigenous survivors and family members,” the family’s statement says.

“Our family is speaking the truth, and it is up to the non-Indigenous communities, governments, institutions, and media outlets to hear our experiences and create a better response to MMIWG2S.”

The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls released it’s final report on June 2019 and made 231 individual Calls for Justice directed to governments, colonial institutions such as police, social service providers, industries and the Canadian population.

Call to Justice 9.5 ii states that police must improve communication with the families of MMIWG2S+ from the first missing persons report “with regular and ongoing communication throughout the investigation.”

In response to the family’s statement, the VPD shares that they were following provincial police protocol.

“Provincial policing standards dictate how police agencies conduct missing persons investigations. These provincial standards include risk assessment, response, and expectations for next of kin notifications,” the VPD statement says.

“The importance of cultural sensitivity and trauma-informed practices can’t be understated, especially when working with families of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. When appropriate, our Indigenous liaison officers, Indigenous Protocol Officer, and Victim Services Unit staff accompany officers when informing families about the deaths of their loved ones.”

IndigiNews reached out to the VPD several times asking whether they would honour the family’s request to come to their homelands for an apology, but they did not respond to that question.

“Unfortunately, in so many cases I’ve been involved in and supported in and even with my own sister that died tragically, I know there’s no cultural safe space or processes for our Indigenous women and girls, Two Spirit and gender-diverse,” says Kukpi7 Judy in response to the VPD’s statement.

“The lack of justice and police accountability, the mishandling, the distrust causes these situations and the discrimination by the police is horrendous and is continuing today. And I believe that the colonial history of forced assimilation, discrimination and racism, oppression and violence by police towards Indigenous women is a big root cause of that.”

Daniel shares that the VPD’s response about standards and practices is meaningless when it comes to actually addressing the ongoing violence experienced by Indigenous Peoples.

“Kwemcxenalqs’s death occurred in that system,” he says.

“And it’s their system; it’s not ours. It’s a colonial system of practice that has deep roots in colonization; they made it themselves. Nobody has to tell them that we’ve been colonized. And when we interact with police, there’s friction. Their system cannot accommodate the deep-rooted nature of our practice.”

When reaching out for responses to the family’s recommendations, IndigiNews heard back from the Coroner’s office, The City of Vancouver, and the B.C. Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions, which underlined their commitments to cultural safety.

Global News also responded regarding the recommendations directed at the media, saying it has “engaged in community consultation initiatives, education and training for our staff” and commits to doing more.

Juanita says although the responses aren’t everything she hoped for — specifically the VPD ignoring their request for an apology — she has faith that things will work out as they are meant to.

“We have laid tobacco and remember that the Ancestors are working with us on this issue that is bigger than us, so the answers might not translate into this world as we think things should be; you have to be able to see far into the future and past to understand the present,” Juanita shares.

“So we have to be ready not to get an answer or [for] anything to change, but we may be inspiring others to speak on what needs to be done through these experiences.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

Samuel Bird’s remains found outside ‘Edmonton,’ man charged with murder

Officers say Bryan Farrell, 38, has been charged with second-degree murder and interfering with a body in relation to the teen’s death

-

Book remembers ‘fighting spirit’ of Gino Odjick, hockey’s ‘Algonquin Assassin’

Biography of late Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg left winger explores Odjick’s legacy as enforcer in the rink — and Youth role model off the ice