‘Witnessing our ancestors’ wildest dreams’: Tla’amin children immerse themselves in ʔayʔaǰuθəm

At the nation, a preschool to Grade One classroom is taught only in ʔayʔaǰuθəm— allowing young children to connect to their ancestral language

As the school day begins in Tla’amin Nation’s ʔayʔaǰuθəm language immersion program, children gather around for the morning exercise: tikkity tikkity məmyɛgi (bumblebee).

The kids clap to keep rhythm, and then, each student introduces themselves and shares how they are feeling — entirely in ʔayʔaǰuθəm.

ʔayʔaǰuθəm is the ancestral language of the Tla’amin Nation, a Coast Salish community located on “B.C.’s” Sunshine Coast.

Koosen Pielle teaches at the language immersion program, called qaymɩχʷqɛnəmšt (qay-mixw qeh-numsht), which translates to “we are all learning the language together.”

“It’s like a little emotional check-in to start off our day and we have our morning protocol together, which includes drumming and singing,” Pielle told IndigiNews.

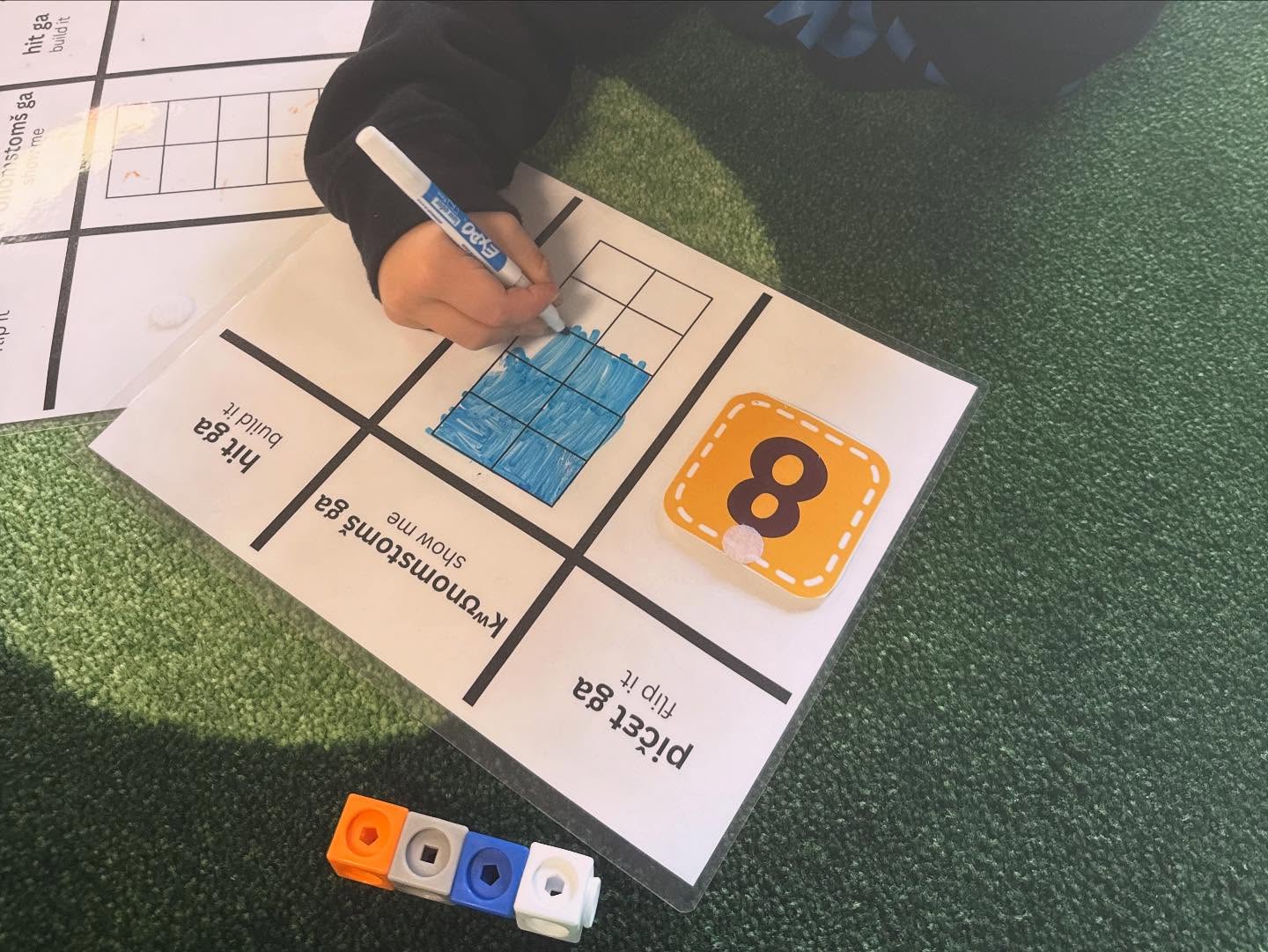

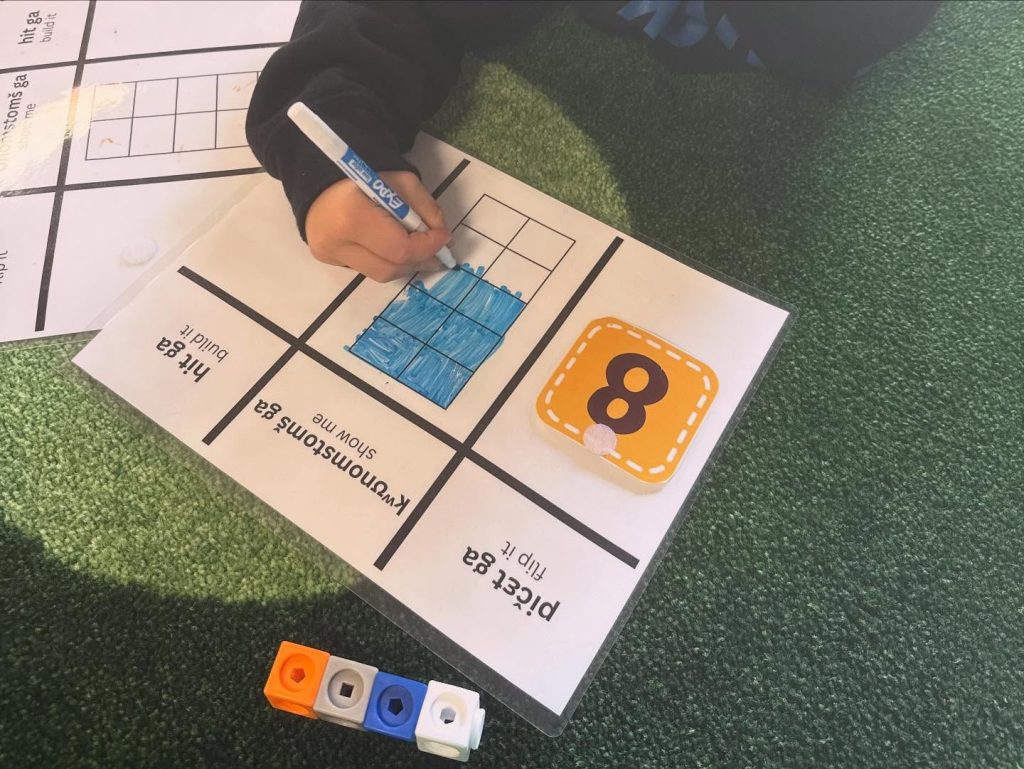

The classroom is an ʔayʔaǰuθəm only space, and each subject or learning activity is taught through the language.

‘I picked up where they left off’

qaymɩχʷqɛnəmšt — a collaboration between Tla’amin and the qathet School District — is currently for preschool students and a combined Kindergarten and Grade One split class, which happens for a full school day, twice a week. Pielle teaches the older group of kids, with a rotation of teachers for each subject.

Teaching the language to preschool-aged children has been ongoing since the ’70s and an ʔayʔaǰuθəm language class has been offered in schools since the ’90s. The immersion program however, launched its pilot year in 2023, and continues to grow each year.

After their morning check-in, Pielle said the class jumps into daily calendars, looking at weather and dates in ʔayʔaǰuθəm. Following daily calendars is math and a snack break.

“And then we usually have some sort of literacy and writing, reading as well — like journal reflections with the students. And we switch back and forth between science and social studies,” said Pielle.

Pielle and her family have been key knowledge keepers and teachers for Tla’amin’s language and school programs for decades. She said she is following the footsteps of her granny and aunts in teaching the language. Along with Pielle, Karina Peters and Alyssa Louie are the other two teachers at qaymɩχʷqɛnəmšt.

“I feel really fortunate that I picked up where they left off, with the current team that I have. This work has been going on for years in our community,” Pielle said.

“The impact is feeling closely connected to the children in the community, but I also feel closely connected to our Elders and our ancestors, and that’s something I remind myself not to take for granted.”

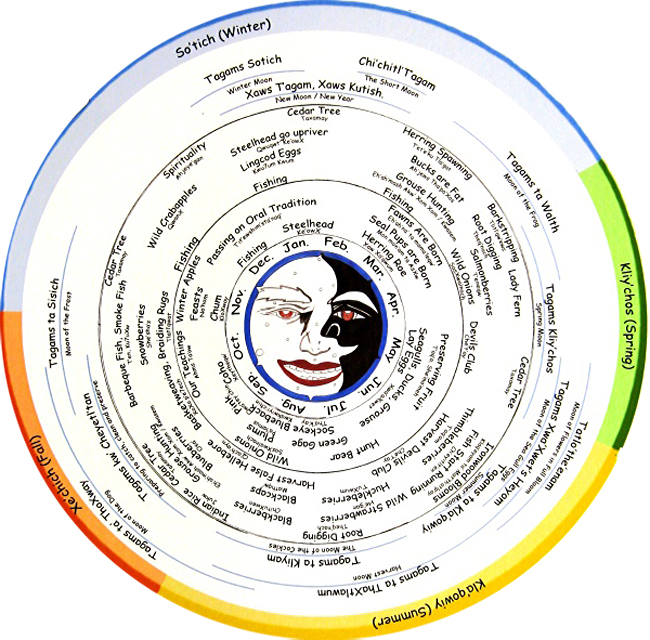

Pielle explained that the program’s curriculum combines the provincial curriculum and Tla’amin’s 13-moons calendar and culturally-relevant teachings.

In the program, the subjects are all seasonal, following the 13-moons calendar. Right now, the class is learning about salmon, because the fall is when salmon are returning to spawn back in the rivers.

“We talked about smoked salmon and barbecued salmon. Going into the winter, it’ll be more of a focus on storytelling, because that’s what our people would have done historically,” she said.

In science, the class talks about their five senses. In social studies, the discussion is around family, the different ʔayʔaǰuθəm words for family, and the different roles in community.

Pielle said it’s “like playing with playdough between the two policies, the 13-moons and then the other curriculum.”

Pielle said the biggest challenge in creating a curriculum for qaymɩχʷqɛnəmšt has been time.

“There was no money to make this happen until there was,” she said, adding that there is a sense of urgency as the community loses Elders who speak the language. First Peoples Cultural Council’s 2022 Language Report cites a total of 238 speakers, 78 being fluent and 160 semi-fluent. Tla’amin Nation is working on its own updated data around fluency after launching a community census earlier this year.

“We’re creating absolutely everything from scratch,” said Pielle.

“So for us, time is a real challenge, but right now, we’re investing our time, and we probably won’t see all of our work come to fruition for a little bit but it’s still worth it.”

Immersion part of a wider language plan

The qaymɩχʷqɛnəmšt program is part of a wider revitalization in ʔayʔaǰuθəm, a shared language between the sister nations Tla’amin, Xwémalhkwu (Homalco), Klahoose, and K’ómoks.

Recently, the Tla’amin governance adopted a five-year revitalization plan for ʔayʔaǰuθəm, which includes five key goals: to expand the language database, strengthen immersion programs, hire more teachers and language leaders, integrate ʔayʔaǰuθəm into governance, community, and daily life, and finally to collaborate on the revitalization with the sister nations.

ʔayʔaǰuθəm was once spoken widely throughout the four nations’ homelands, but was lost in many families because of its attempted extinguishment in residential “schools,” where children were forced to speak English.

The ʔayʔaǰuθəm database has a growing 6,530 words and 8,901 phrases recorded, according to Tla’amin. The revitalization plan aims to document and log a total of 22,000 entries of 10,000 words and 12,000 phrases in the FirstVoices platform. In the plan document, the nation said typically 20,000 words and phrases is considered a “critical benchmark” for language revitalization.

Another key part of the strategy includes strengthening the qaymɩχʷqɛnəmšt program by adding additional days, expanding the program to go up to Grade Three, including Elders in the classrooms, and expanding resources and materials for the classroom.

Pielle said already this year, they are already starting to teach students to read the written form of ʔayʔaǰuθəm.

“It was kind of like a social experiment; how young can you teach someone how to read our language?” she said. “And with the help of Karina and Alyssa, we’ve been teaching the orthography through an alphabet song and we have a letter of the day. That’s something that I’m really proud of.”

Brandon Louie, an elected Tla’amin executive council member and housepost of čɛčɛgatawɬ (Community Services), said the plan brings excitement for the future.

“Our qaymɩχʷqɛnəmšt, which is the immersion program, it’s quite amazing to see the kids, and how well they absorb the language,” Louie said.

A housepost is a key component that makes up Tla’amin Nation’s House of Governance. There are houseposts for community services, lands and resources, finance and admin, capital and infrastructure, governance, and economic development. Each housepost is overseen by an executive council member and governance is overseen by the hegus (chief).

Not only does the nation hope to grow the qaymɩχʷqɛnəmšt program, but it also hopes to expand the adult immersion program which is in its pilot year through the University of Victoria (UVic). Louie said the course has been running for a little over eight weeks and has nearly 50 adult participants.

Completion of the course will provide the student with a certificate in Indigenous Language Proficiency.

“Another part that excites me is trying to bring out the silent speakers. These are the individuals who know the language but don’t necessarily speak it, or they’re not confident, or shy in public and it doesn’t come out,” Louie said.

“So trying to get them into places where they’re comfortable and amongst each other, and being able to maybe learn new words emerge.”

The nation said this will be done through “silent speaker gatherings” which will be small group settings that are “designed to promote comfort, connection, and re-engagement with the language.”

The gatherings will have conversational practice facilitated by Elders and fluent speakers. And include activities like storytelling, shared meals, and guided dialogue to encourage participants to use ʔayʔaǰuθəm in a “low-pressure setting.”

In both adult and child immersion programs, Tla’amin hopes to expand staff for additional ʔayʔaǰuθəm teachers. Pielle said currently, there are four, each with a different age group.

“We’re all spread so thin. So I’m really looking forward to the next up and coming teachers in our village to sustain our language long term,” said Pielle.

The nation will also introduce a “master-apprentice” model, which will pair up fluent Elders and master speakers with motivated learners to offer one-to-one learning.

‘We hold a responsibility to the language’

Louie said another part of the revitalization plan is to bring ʔayʔaǰuθəm into governance and daily lives.

“We all hold a responsibility to the language, to our people … we gotta move that into our governance piece,” he said.

“And I think everybody’s on board. It’s just a matter of getting into operations.”

Already to support this, the nation has put up street signs in the community that incorporate ʔayʔaǰuθəm and English as well as into newsletters, social media and other documents.

He said similarly to Tla’amin, Xwémalhkwu, Klahoose, and K’ómoks all have their own five-year plans, too.

“It’s all really amazing work, and it’s just about coming together, sharing. One of the big things that was an outcome from that language gathering, was the sharing of resources,” he said.

“Everybody’s kind of like, we have our immersion teachers, we’ve got our adult language teachers, we’ve got our high school teachers. We’ve got all these people doing their work in their space, but they’re not necessarily able to cross those platforms and share their resources. And it’s the same with the sister nations.”

He mentioned that with Tla’amin’s immersion program, they have a strong teacher team who’re able to develop curriculum and materials “on the fly.”

“That’s partly due to the fact that the program hasn’t been well established. They don’t have all that [materials], so they’re developing all of these resources within their class… Other nations can benefit from those resources, and we can benefit from what other people are doing,” he said.

“The more we can get together and talk about those things, we’re all going to benefit together.”

Similar to Pielle, language has been a part of Louie’s life since he was a kid.

“My uncle Fred was my language teacher until he passed … he was really funny with the language and how we used to talk about it,” he shared.

“There’s a place name we have here and it’s kʷʊkʷʊkʷθays, which is the Ragged Islands (Copeland Islands), and means ‘they’re all broken up.’ He described my language as all broken up like those islands, I only know a little bit here and there.”

He said, at high tide, the islands are broken up — but at low tide, they are connected, and you can walk from one island to another.

“That’s kind of like the symbolism for our revitalization plan. To connect all of these plans together and initiatives. To keep on that work and eventually we’ll be in a good place.”

He said back when he was in elementary and high school, there were language courses students could take, but didn’t have a well-developed curriculum.

“You get to a point where you plateau. But now we’ve done a huge amount of work. This was probably 30 years ago. So, over that time, we’ve got to a place, we have all these resources, and we have all these speakers, and the language is truly who we are.”

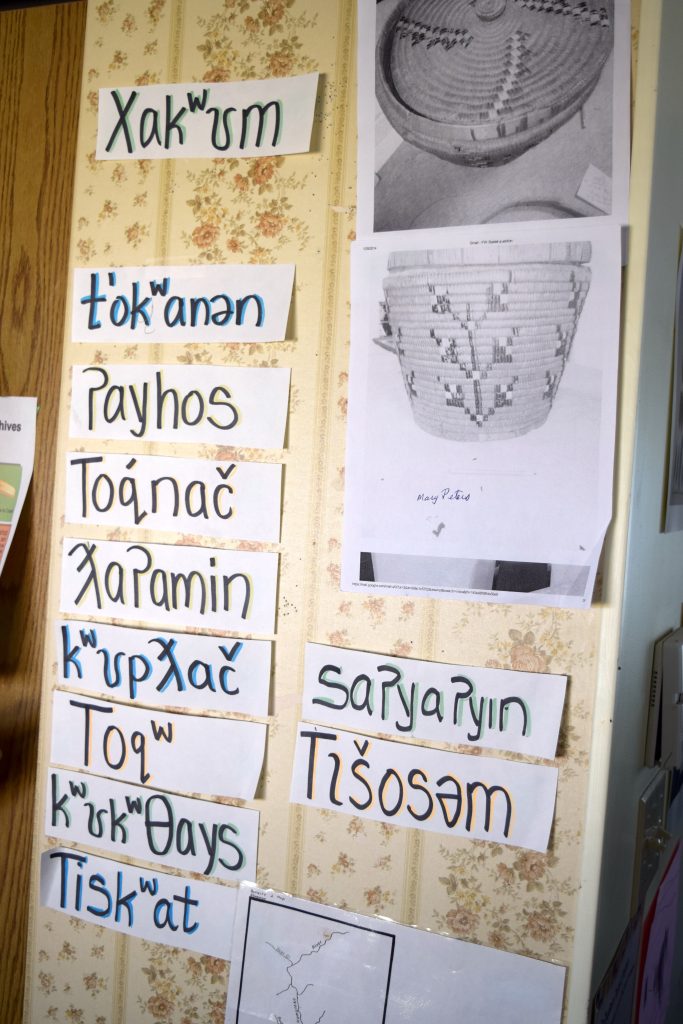

Louie said whether it’s a word or phrase for animals, the land, places, people, or what people are doing, they relate to “just everything about who we are and what we were doing on our territory and on our lands.”

“The way they [ancestors] name places and things, it’s just beautiful. Some of the words are just perfect in terms of how they describe the place — you get there, and it’s like ‘oh, yeah, I know exactly why they call this,’” he said.

He gave the example of Tla’amin’s village name t̓išosəm, which means “milky waters from herring spawn.”

“These types of words, I just find them really, really beautiful, it connects you to who you are.”

Pielle said she’s looking forward to the future and is very proud of how far the language program has grown and watching the students learn and participate in culture.

“Every morning, we have morning protocols. We do drumming, singing, and dancing with students. I’m very proud of that part of the day,” she said.

She said, being in her 30s, she didn’t have the same opportunities as a child to feel proud of being Tla’amin. When she sees the immersion students at community events getting up on the floor to dance and sing, she feels how important that is.

“That’s just so impactful for me as an older Indigenous person, to see our little ones be proud of who they are and where they come from and have no ounce of shyness in them,” she said.

“I feel like I am witnessing our ancestors’ wildest dreams. You know, the right to teach our language, the right to teach our culture.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

At the Salish School of Spokane, a community of n̓səl̓xčin̓ speakers is built

Students ages one to 13 are immersed in the Colville-Okanagan Salish language — learning alongside their teachers and families

-

‘Truth, courage, care’: Esk’etemc leader honoured with ‘B.C.’ reconciliation award

Charlene Belleau has been ‘leading voice’ of justice for survivors — documenting truth and supporting community healing