‘State of crisis’: Social workers too overwhelmed to adequately care for children, says RCY report

The latest investigation from Jennifer Charlesworth examines MCFD’s frontline workforce and the ‘urgency’ for government to act

More than 80 per cent of social workers in the province’s child welfare system are overwhelmed with high caseloads and the workforce is reaching “a state of crisis,” according to a new report.

Jennifer Charlesworth, the B.C. Representative for Children and Youth (RCY), released “No Time To Wait” on Tuesday. Her latest investigation reveals the severity of social worker staffing capacity at the Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD).

“No Time To Wait” comes on the heels of last week’s report, “Don’t Look Away,” which detailed the tragic case of an 11-year-old First Nations boy known as Colby, who passed away after being starved, beaten and tortured by extended family caregivers.

That report found that the social worker assigned to Colby’s case did not see him for seven months prior to his death.

“We have known about chronic understaffing at this ministry for decades, yet successive governments have not addressed these challenges,” said Charlesworth in a statement.

“Now, here we are yet again, reeling from the death of a child that was entirely preventable.”

MCFD workforce characterized by ‘stress, burnout and fear’: RCY

This latest report is part one of two looking specifically at MCFD’s capacity to care for children. The fast turnaround is in recognition of the “urgency” for MCFD to act immediately, said Charlesworth.

“Indeed, the evidence suggests that MCFD’s social worker workforce is in — or is close to — a state of crisis,” Charlesworth writes in the report, “with persistent and substantial understaffing, unmanageable workloads, an inability to routinely implement practice standards, and an unhealthy work environment characterized by undue stress, burnout and fear.”

Part one of the report provides an overview of findings from the responses of more than 700 ministry social workers, team leads and managers, who took part in an online survey conducted by the RCY in April and May of this year.

The report also includes findings from focus groups held with social workers, community engagement sessions including with First Nations and Métis leadership, and a review of previous reports, ministry documentation and data.

Part two, which is set to be released after the October 19 provincial elections, will deep dive into data and narratives that arose from focus groups, and further review hundreds of pages of testimony from social workers, said Charlesworth.

According to the social workers and team leads who participated, 81 per cent said their workload does not permit them to effectively support the children, Youth and families, while 78 per cent said they are unable to keep up with their administrative work on a weekly basis.

“There is no possible way that we can adhere to timelines and best practices with the large caseloads we carry and the lack of admin support,” said a social worker in the report.

“I feel well supported by my colleagues, team lead and director of operations, but incidents will sit for weeks after the initial call because there is not enough time or people to complete it.”

‘We need a fundamental rethink’

Charlesworth emphasized that today, people are more vulnerable to complex circumstances such as the toxic drug supply, housing shortages, the cost of living, the mental health crisis and COVID-19.

“All of these things combine to make this feel really difficult,” she said.

Nearly half of social workers admitted they are unable to meet the ministry’s standards and policies, which require an 85 per cent compliance rate.

During a press conference launching the report, Charlesworth noted there have been questions around whether MCFD’s standards and policies are up to par.

One of MCFD’s standards, for example, is to visit with a family once every three months, whereas Indigenous Child and Family Services have social workers visit with families every 30 days, she said.

Right now, Charlesworth said, even if MCFD wanted to, it isn’t in a position where it can choose to be more rigorous, given nearly half its social workers aren’t meeting the ministry’s less rigorous standards.

The report highlights the problematic emphasis MCFD gives to measuring how busy a social worker is by the number of caseloads they have.

“Not all cases are equal,” said Charlesworth. A social worker could have fewer cases, all of which are complex, and have a higher workload than another social worker with a greater number of less complex cases.

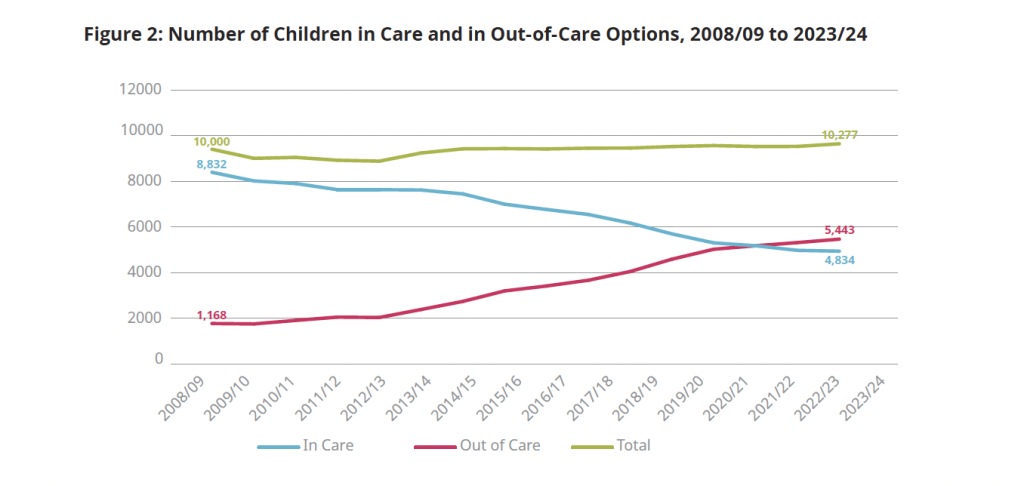

Data in the report shows how a reduction in the number of children in custody results in just as much, if not more work for social workers — whose jobs are to find, reach out to, assess, develop plans and agreements with, and support the transition to extended family caregivers, such as in Colby’s case. According to the report, social workers informed the RCY that out-of-care options typically require more work than bringing a child into custody.

Between 2017 to 2019, the ministry used a “workload measurement tool” to measure both caseload and type, helping to fairly assess a social worker’s true workload, but in 2021, abandoned the tool.

MCFD has not made the results of the workload measurement tool publicly available to workers, or the public, but Charlesworth said that the tool indicated that several hundred more social workers would be needed to meet MCFD’s 85 per cent standards compliance rate.

Minister Lore did not provide an explanation as to why it abandoned the tool, or how it is currently measuring its workloads.

However, she said that in the last year, there has been a 17 per cent increase in frontline staffing and that she is “hearing directly from social workers what their needs are, what their families’ needs are.”

“We need a fundamental rethink, a reimagine, of ministry services and support, and how we work with other ministries,” she said.

‘Urgent’ circumstances

An additional problem, the report finds, is that rather than addressing foundational issues of social worker understaffing, MCFD has created more procedural work for itself.

For example, in the 2024 budget, MCFD opened a “Child Safety, Oversight and Practice Development Branch,” funding 40 “oversight” managers, which according to the RCY, will likely be filled by existing MCFD field staff, who are already overworked.

“Increasing capacity to track and oversee direct service work, before ensuring that there is sufficient staff capacity to do the direct service work, seems misguided” said Charlesworth.

In a response to “Don’t Look Away,” Our Children Our Way Society, which supports Indigenous Child and Family Services, said that the report highlights “an outdated and broken child welfare system that was never designed to support Indigenous families or achieve positive outcomes for their children.”

In part one of the report, the RCY recommends a number of “immediate steps” for MCFD to take.

These include enhancing training, redeveloping a social worker workload management tool, ensuring funding is available to support recruitment and retention, a health and wellness plan for child welfare staff, and to move away from blaming social workers in circumstances where there are clear systemic inadequacies.

According to Charlesworth, the ministry has acknowledged many of the issues highlighted in the report, and has taken steps to improve the conditions for social workers, including relaxing policy requirements in critically understaffed areas, and establishing a remote team to help with administrative tasks.

As of May 2024, MCFD has also established a Jurisdiction Team to receive and refer child protection reports to Indigenous Authorities, to serve as a 24/7 hub for inquiries related to jurisdiction agreements, and share information afterhours to support child safety responses and planning.

Though part two will include final, detailed recommendations, Charlesworth says circumstances are “so urgent” that there is no time to wait.

“These are practical steps that I expect the ministry to take now,” said Charlesworth. “This is a vital workforce that has not had the focused attention it requires for too long. I am expecting that the clear and urgent calls social workers are making will finally be heard.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Truth, courage, care’: Esk’etemc leader honoured with ‘B.C.’ reconciliation award

Charlene Belleau has been ‘leading voice’ of justice for survivors — documenting truth and supporting community healing

-

Across the border, Indigenous fears spike amidst ‘U.S.’ immigration crackdown

With ICE operations, multiple First Nations warn members about travel risks — despite treaty rights. Why Indigenous communities are on the frontlines defending rights for all