OKIB Elders feel humbled after receiving joint honorary doctorate

Chris Marchand and Eric Mitchell were honoured for creating a UBCO program on cultural safety and for sharing how colonialism has affected them.

Last year, an exciting and humbling experience, couple Christina “Chris” Marchand and Eric Mitchell were nominated by the faculty at the University of British Columba Okanagan (UBCO) for an honorary doctor of law degree.

They were nominated for their work in creating and teaching the school’s Cultural Safety Program .

“I should say prior, we were told that nothing was going to happen until next year with this because of the COVID-19, and so we thought, well, okay, you know, we were a bit disappointed,” Marchand says.

But then, a week ago the two found out they were going to be this year’s recipients.

“It was a really good surprise and still it is sinking in a little bit, you know when people congratulate us from everywhere,” says Marchand. “I realize it’s kind of humbling.”

Marchand and Mitchell are members of the Okanagan Indian Band (OKIB), and have been working at UBCO and teaching the Cultural Safety Program since 2008.

They not only created the program, but, as adjunct professors, have been teaching the course, which focuses on the history of Canada’s Indigenous Peoples. The class was initially for third-year nursing students, but recently expanded and is now available for all students and faculty.

Marchand and Mitchell have been life partners for 48 years, and share two children and three grandchildren.

A journey from your mind to your heart

Marchand is a Sixties Scoop survivor and Mitchell is a survivor of the residential school system in Kamloops, B.C.

They say they have dedicated their life’s work to educating non-Indigenous students and faculty. They share their truth and the intergenerational trauma with students so that future generations of non-Indigenous people can reconcile.

“The majority of non-Natives don’t think very well of our people, so they already have preconceived notions and ideas and thoughts, and most of it is negative,” Marchand says.

The Cultural Safety Program spans four days, each of which is six hours long. Students are not allowed to take notes during the program.

“Because what we want to know at the end of the day is what’s in your heart,” Marchand says.

Marchand and Mitchell say they want to change people’s minds about how colonialism has affected the Syilx/Okanagan Peoples.

“It seems to be having an impact,” Marchand says of their university program.

Their journey

The Sixties Scoop refers to a practice that was orchestrated by the Canadian government and began in the 1950s. It involved Indigenous children being taken or “scooped” from their homes on the reserve and placed into primarily white foster homes.

“It was in 1966, when me and my siblings were taken from our home,” Marchand says., “Even though it’s been that long ago, it’s not an easy thing to talk about.”

This was most often done without the consent of the children’s families, according to the First Peoples Child & Family Review article “Identity lost and found: Lessons from the sixties scoop” by University of Regina professor Raven Sinclair.

“You know, having somebody else come in and say, ‘You’re not good enough to have your children or to raise your children, we’re taking them’ is wrong,” she says.

“One day, a long time ago, a friend or acquaintance, we ran into each other, and she had to ask me, she said, ‘Chris, I need to ask you, how was it in the foster home? Like, how did they treat you?’”

“And I told her, well, I don’t know, but if you get a whipping with a rubber hose, then I shouldn’t have to tell you any more than that,” she says.

“She was a neighbour, non-Native neighbour, and when I was little, I was able to visit them once in a while and, to me, that was my safe haven without them really knowing that it was.”

From surviving the Sixties Scoop to becoming a professor at UBCO where she is able to share her experiences, Marchand’s journey has been a complicated one. .

“Sharing our story stories isn’t easy, and it isn’t easy for people to hear it, so we have to create that safe place,” Marchand says.

She feels she and her husband are accomplishing this through their work at UBCO.

“I’m starting to think about what I need to do as a teacher to help students feel more comfortable at the university and to succeed,” she says.

As that is the biggest part of their work with faculty and students started having to go through The Cultural Safety Course more frequently .

“I give full credit to the Unity Ride [Unity Ride was from 1996 to 2004 – an annual Spiritual Ceremony with horses] for bringing me to the table and to the classrooms to be able to talk to non-Native people,” Marchand says.

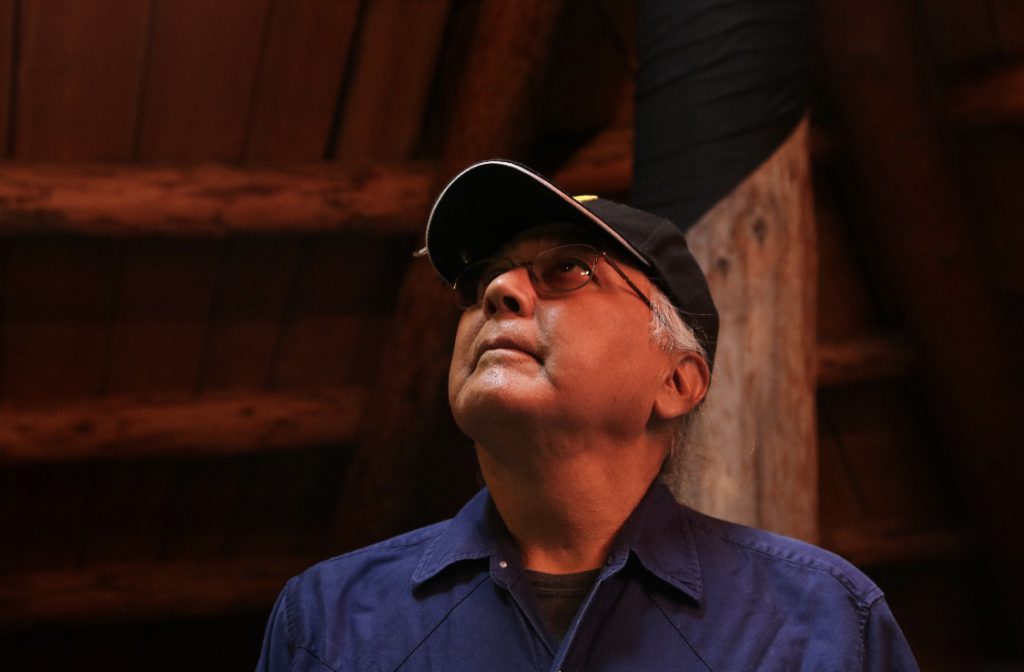

Eric (Np̓əppaxʷikn) and his journey

“One day I was saying to my uncle , what does a person have to do to get an Indian name around here? I rode all across Canada that should count for something.” Mitchell says.

“After our Unity Ride, you know, we traveled with that for 10 years, and well, my grandfather, his name was Np̓əppaxʷikn.”

“So my name is Np̓əppaxʷikn, linguistic say, it is a diminutive of that, meaning there’s my grandfather and I have the same name, but a smaller name, I got that not very long ago, 15 years ago.”

The translation of the Np̓əppaxʷikn name in Nsyilxcən –the Syilx language – to English is “little light on the back of a mountain or ridge.”

As a survivor of the residential school system, Mitchell was displaced from his family at a young age. His mother had passed away when he was six years old and, at the time, he was being raised by his late single father.

“I wasn’t taken like in a lot of people’s stories,” Mitchell says.

Residential schools were created by the Canadian government and were administered by Christian churches., They first began operating in the 1880s, and were established to remove Indigenous children from their families and assimilate them into Euro-Canadian culture.

“All of my uncles and aunties, one by one, they all took turns looking after us,” he says.

He says he was taught how to hunt, fish and follow traditional practices from his uncles before and after his time at residential school.

“I was on the mountains, a lot of my teen memories were about hunting,” Mitchell says.

From Mitchell’s early childhood, he remembers a priest would come over to his house frequently. The priest would talk to his father for some time.

“Thinking back on that time, that priest was talking him into sending us there,” he says.

“And he would bring what look like comics, but they were actually Bible stories in there.” Mitchell explains that he went back and forth from public school to residential school for a small duration of his childhood. His father didn’t like the idea of sending Mitchell and his siblings to residential school, however.

“But then the welfare lady in town, she threatened my dad, ‘You send your kids to school or you’re going to jail,’” he says.

“We all were treated pretty badly,” Mitchell says. “Everybody got whacked in the back of the head, we all got strapped, we’ve got scars, we got scars that we can show anybody what that school gave to us.”

Mitchell’s father passed away when he was 13 and he was away at residential school. He says he was told that he could finish his year there, but could not return in the fall because he was an orphan.

“On one hand, I was glad to never come back. But on the other hand, it felt like I was thrown away,” Mitchell says. “I can’t remember, like, big chunks of my time there because it was so emotionally traumatic.”

After Mitchell’s last year at residential school, he was put into a foster home on the OKIB reserve with his uncle. He now considers himself a lifelong student of the Syilx/Okanagan language, culture and traditions.

“So, I’m like a sponge, every little thing that I can get from people,” he says.

“That’s what Cultural Safety is all about, is getting them to a place where they can see us as equals, see us as human beings, see us as partners and building this country.”

Finding truth and reconciliation

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was launched in 2008 by the parties involved in the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. It’s purpose was to recognize the Canadian government’s wrongdoings against Indigenous Peoples. It was also meant to provide those impacted by the residential school system with an opportunity to share their experiences.

Mitchell speaks to truth and reconciliation as a part of the Cultural Safety Program.

“We can say confidently that 99 per cent of Canadian public knows nothing about our people, about Indigenous people in Canada,” Mitchell says.

He and Marchand believe that society has the wrong idea of what truth and reconciliation means.

“The white people out there, too many of them think that we have to reconcile and they’ll just wash their hands and let’s forget about the past,” Mitchell says.

Mitchell believes that society needs to reconcile by taking ownership of the wrongful actions of the Canadian government. But also by acknowledging Indigenous people’s history, and making sure what happened in the past won’t happen again.

“They need to hear our story, the truth of how much it damaged our people and what all those little things the government did to try to annihilate us basically,” Mitchell says.

“Because if they knew what our people go through, maybe they’ll stand beside us and fight for our rights.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

Short film showcases the inspiring story of Dana Tiger — and a family design legacy

Muscogee artist’s life, work, and fashion business are the subject of Loren Waters’ Sundance-acclaimed documentary ‘Tiger’