‘You don’t call him Ogopogo, you call him by his name, nx̌ax̌aitkʷ’

Syilx knowledge keeper shares why it’s important to feed Nx̌ax̌aitkʷ, the sacred being in the water

As waves gently lap the shore of Okanagan Lake in Syilx territory in so-called Peachland, B.C., Xwayluxalqs — or Tricia Manuel, as she’s known in English — speaks about her responsibility to care for nx̌ax̌aitkʷ, who in turns cares for the people.

Xwayluxalqs (Fox Dress) is a Syilx traditional knowledge holder and carrier of the Syilx puberty ceremony.

She introduces herself and her kin in nsyilxcən, the Okanagan language.

“I am the granddaughter of the hereditary chief and all of my life I was taught you put yourself last and you do the work for the people, you help the people,” says Xwayluxalqs.

Raised to give back, she says one of her cultural responsibilities is to remind her community about the importance of feeding nx̌ax̌aitkʷ (pronounced N-ha-ha-eet-kw), commonly known to outsiders as “Ogopogo.”

Who is nx̌ax̌aitkʷ?

The name nx̌ax̌aitkʷ is layered.

When broken down and translated to English, the “N” means inside, and “x̌a” means sacred, so “x̌ax̌a” means very sacred, and “itkʷ” means water, according to Elder and knowledge holder Yamxwa (Cedar Basket), Marlene Squakin.

Yamxwa is Syilx, from smelkmixw or Similkameen (Valley of the Eagles).

“So that’s what nx̌ax̌aitkʷ means, it literally means, ‘There is a sacred being in the water,’” says Xwayluxalqs.

“And that sacred being takes care of the water, and that’s not just Okanagan, but all the water systems throughout the Okanagan Nation.”

According to the captíkʷɬ (oral stories of Syilx laws), nx̌ax̌aitkʷ travels throughout the waters, caring for them.

“That part of who nx̌ax̌aitkʷ is is important to our people. He reminds us of the sacredness of water, and part of what I do all the time is to remind the ones that I work with that we are all made up of water,” says Xwayluxalqs, as the waves gently lap the shore of Okanagan Lake.

While nx̌ax̌aitkʷ is sacred to the Sylix, settler folklore often paints nx̌ax̌aitkʷ — or the “Ogopogo” — as a lake demon, a monster or even a big, friendly lake serpent. And this is harmful, she explains.

“For so long so many of our ceremonies and our stories were asleep, and our knowledge was minimized because of colonization,” she says.

Now she sees “stuffies of Ogopogo” and people diving in the lake to try and catch a sighting, and she feels “that’s minimizing and tokenizing something that’s sacred to the original peoples of this land.”

It’s important to her to correct misconceptions created by settler society.

She shares that the late Elder, Joey Pierre, taught her, “You don’t call him Ogopogo, you call him by his name, nx̌ax̌aitkʷ.”

Feeding nx̌ax̌aitkʷ

When Xwayluxalqs speaks of her work, she’s not talking about her job. She speaks of the work she’s doing for her people — standing ceremonies up again, and reminding x̌ax̌a youth who are going through rites of passage that doing ceremonies to care for the land is vital to the continued existence of the people.

“In the work that I do with the Swinumtux [the beautiful ones], I tell them, ‘We do this so that your grandchildren are going to be okay, and remember that this water was prayed for by our grandmothers and grandfathers, and now we’re here doing this work,’” says Xwayluxalqs.

She remembers a time when respected elder, late Joey Pierre, whom she fondly called “uncle”, told her about how he would go out in a rowboat to feed nx̌ax̌aitkʷ. He passed the ceremony to her, she says, and asked her to continue the work so their people wouldn’t get lost.

“I’m telling you to take care of nx̌ax̌aitkʷ in a good way,” he told her, so she started to care for nx̌ax̌aitkʷ as she was instructed. Now she teaches the ceremony to young men as part of their puberty training in order to keep this important ceremony alive.

Boys are the hunters for this particular ceremony, and are the ones who offer the deer to the water — and the water is the female energy, says Xwayluxalqs.

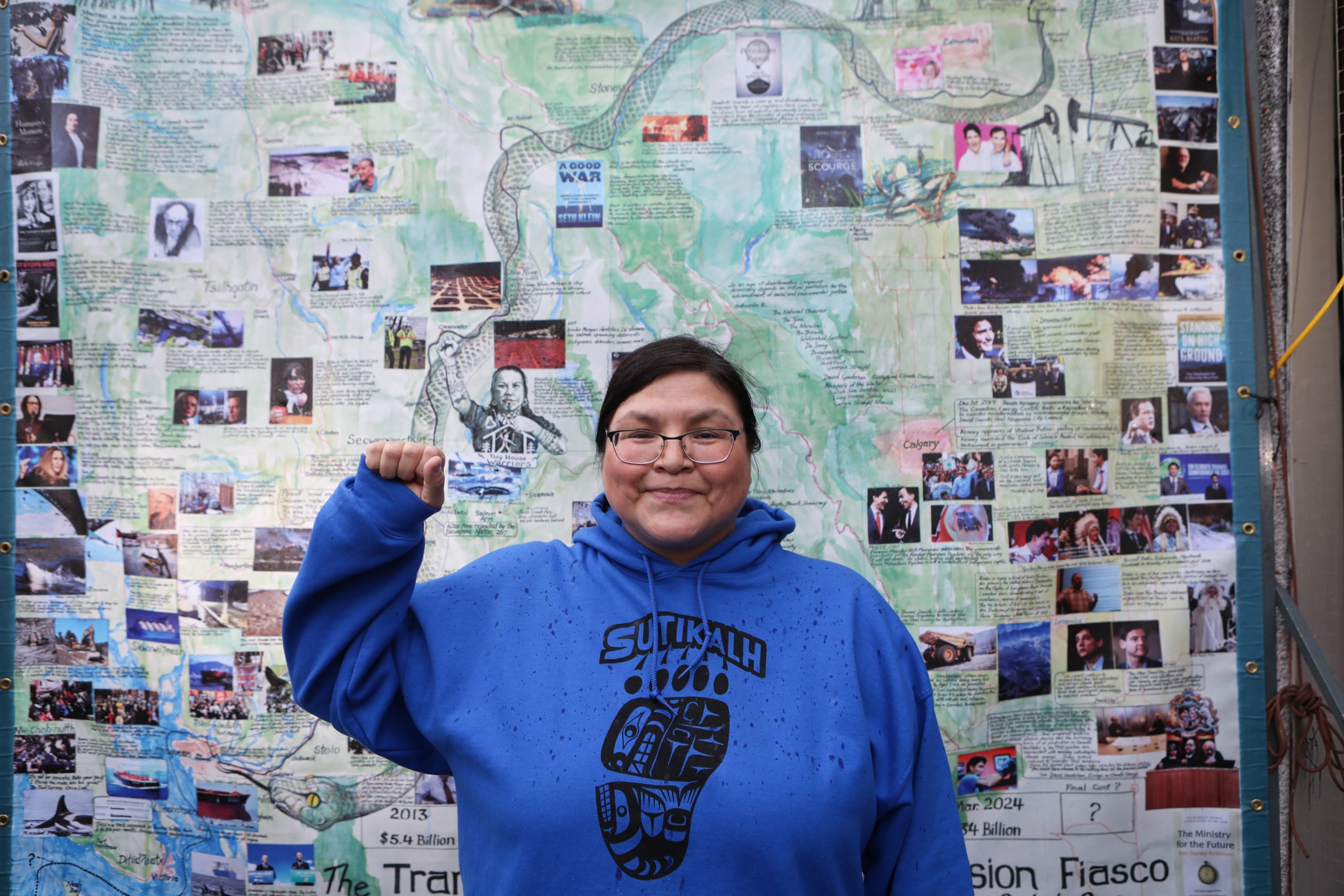

“My brother Bruce [Manuel] is the one who takes the boys out on the boat,” says Xwayluxalqs.

“He teaches them, talks to them about what their responsibilities are as caretakers of the land, as keepers of this ceremony, and that they are always to remember to do the offering.”

When the boys are out on the water, the women stand on shore and sing, praying for nx̌ax̌aitkʷ, asking him to keep the water clean and clear and protect the people, she explains.

“Praying that no one drowns or dies, whether they are on a boat, or driving along the lake — that’s our prayer, is that people are safe around this water,” Xwayluxalqs says. “For the birds, the four-legged, the crawlers and swimmers. All of life needs the water to be clean, so that’s our prayer.”

‘A time of prophecies’

“We are living in a time of prophecies,” Xwayluxalqs says.

The prophecy states that there will be a time where people buy bottled water and wars will be fought over water, says Xwayluxalqs.

Xwayluxalqs says she was told by her late uncle Herbie Manuel, that when Syilx people see sacred beings such as nx̌ax̌aitkʷ, cəcam̓aʔt iʔ sqilxʷ (the little people), or sc̓wanáytm (Bigfoot), it is a sign of good luck, an experience to welcome rather than fear.

“You’re supposed to acknowledge [nx̌ax̌aitkʷ] and ask him for what you want and tell him thank you for being here,” she says.

“You’re not supposed to disrespect him, and you’re not supposed to try and call him to you. You’re not supposed to say, ‘Well, where are you? I need you. Come help me.’”

Sacred beings are a part of our land, for a purpose, she continues.

These beings are here to remind us of our responsibility as Sqilxw to do all that we can to take care of the land, says Xwayluxalqs.

Yamxwa agrees.

“We know our land like the skin on our body,” she says “Based on 10,000 years of observation and knowledge stored in the language.”

There are layers to this story, and to other stories about these beings, reserved for the Syilx people.

“Only the best and truest knowledge was shared because the survival of the next generation may depend upon it,” shares Yamxwa.

Xwayluxalqs asks that all people respect the sacred work she and other Syilx people are doing.

“I am to always ensure that the ones coming up behind me know their responsibilities and know their connections to the land and to the water,” she says.

IndigiNews would like to thank Sarah Alexis of Inkumupulux for her language contributions to this story.

Author

Latest Stories

-

Nuxalk girls’ basketball team wrapped in support after championship win: ‘Everybody was cheering for us’

The Acwsalcta Thunder became provincial champions at the 2026 B.C. School Sports Provincial Tournament — emerging as the top of 16 high school teams