‘I hope there is closure’: Families of MMIWG await results as possible remains found at landfill

As the discovery is made less than three months into probing the Prairie Green site, loved ones of Morgan Harris and Marcedes Myran are emotional

Content warning: This story contains details about the MMIWG2S+ crisis. Please look after your spirit and read with care.

The loved ones of two missing and murdered Indigenous women in “Winnipeg” are emotional as they wait to find out more about possible human remains that were uncovered during a landfill search.

A probe of the Prairie Green site came to a temporary halt on Wednesday morning as the discovery was made.

Families of the late Morgan Harris, 39, and Marcedes Myran, 26, were immediately notified and gathered at the landfill on the northwest outskirts of the city.

While the women’s loved ones are not able to discuss specific details of the investigation as it’s ongoing, they came together the next day to share their reactions to the discovery.

“I kept saying from the time that the landfill search started, it could be any day,” said Melissa Robinson, the cousin of Harris, during a press conference on Thursday.

“That day has arrived.”

Jorden Myran, the sister of Myran, thanked everyone who supported and advocated for the search, saying “this is the day that we’ve been waiting for.”

“Although it’s a good thing that we found the remains, it’s also very, very hard,” she said.

A Province of Manitoba bulletin said the RCMP and the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner are involved and “steps for identification are underway.”

It will take at least two weeks to identify the potential remains, according to the province, and more information will be released as facts are confirmed.

“The shock of everything has finally hit me,” Robinson said. “I’m pretty emotional today.”

The search — which involved excavating waste from the landfill and then sifting through it all to try to find the women — began on Dec. 2, 2024.

Elle Harris, the youngest daughter of Harris, said she wasn’t expecting results to happen so soon.

“Because of how hard we had to fight for this and how hard we’ve been fighting for the past two years, I wasn’t prepared,” she said.

Harris — who just turned 18 — also spoke about how much she misses her mother.

“I’m doing a lot better than where I was two years ago, and I’m on my journey of healing,” she said.

“But every day, I just think ‘I want my mom.’ I want her to be there for me. Because it’s so hard.”

“Manitoba” Premier Wab Kinew spoke with reporters, including IndigiNews, at a media scrum in his legislative office on Wednesday.

“I don’t think any of us are ever going to forget today, I think all of us, who are there, family, searchers, people from governments such as myself, are still in the state of, ‘is this really happening?’” Kinew said.

“These families really made us do the right thing.”

He explained that after one of the two search teams found remains, that the second search team acted as a “second set of eyes.”

Two forensic anthropologists were on site, one started identifying what was found, the other was there to “double confirm.”

Kinew said that the searchers have been looking at dates on milk cartons and addresses on envelopes to help them “hone in on” where exactly to search at Prairie Green, based on the timeline and location of when Harris and Myran went missing.

“I just want to commend the people who designed the search and the search technicians and the forensic anthropologists on site, and everybody who’s put together a meticulous process here,” Kinew said.

He called the discovery a “testament to the care and the attention to the fine level of detail” that was laid out in the search plan.

“The search technicians are really motivated to get back in there,” Kinew said.

The search resumed on Thursday, according to the province.

“I hope there is closure coming for one family,” Kinew said.

“But we know that we have to keep working for the other family, and potentially, again with that uncertainty we may have to continue the work.”

A promise to search the landfill was part of Kinew’s campaign before he was elected to office in October 2023.

When serial killer Jeremy Skibicki was charged with first degree murder in December 2022 for the deaths of Harris, Myran, Rebecca Contois, and an unidentified woman that was named Mashkode Bizhiki’ikwe (Buffalo Woman), the Harris and Myran families faced opposition from the Winnipeg Police Service, and the former Progressive Conservative provincial government, who seemed dismissive of pleas for a landfill search.

Heather Stefanson, former premier, said that with a search “comes long-term human health and safety concerns …. We cannot knowingly risk Manitoba workers’ health and safety for a search without a guarantee.” Former police chief Danny Smyth reportedly said that too much time had passed to start a search.

During her campaign for re-election, Stefanson’s PC party paid for ads pledging to “Stand Firm” against a landfill search, which politicized the families’ plight.

“It makes my blood boil to know that they’ve dragged us these last two years through all this anguish, all this hurt, all this sorrow, all this fighting,” Robinson said.

“We were constantly told ‘no’ because it couldn’t be done, or, it was like looking for a needle in a haystack, but here we are less than three months of the search commencing.”

She recalled how in December 2022, before boarding a plane to “Ottawa” for a meeting with the feds to lobby for a landfill search, that the Winnipeg Police held her up to show her a PowerPoint presentation explaining reasons why a search was not feasible.

“If people would have just listened to us in the first place, we would have brought these women home a lot sooner, they didn’t deserve to sit in that landfill,” Elle Harris said.

“No person should go through what we went through, and again, to every one of you that said no to every one of you that didn’t believe in us, do better.”

At Thursday’s presser the family members were supported by Anishinaabe Elder Geraldine Shingoose and the newly elected AMC Grand Chief Kyra Wilson, who was previously the chief of Long Plain First Nation, where Myran and Harris are from.

Wilson spoke of the grand chief who held the role before her, the late Cathy Merrick — a Cree woman from Pimicikimak who was a “fierce advocate” for the families. She suddenly collapsed outside the Manitoba Law Courts in September 2024, and died in the hospital.

“She walked that fight and this journey every single day,” Wilson told reporters. “The love that she had for the families, it’s such a beautiful thing that we were able to share that time with her when we were fighting to search the landfill.”

Merrick was known for her strong voice, her life-long commitment to advocating for Indigenous rights, the wellbeing of First Nations communities, and justice.

When she spoke at a red dress jingle dress special in honour of Myran and Harris at Long Plain First Nation’s powwow in 2023, she told the crowd, “I’m so grateful that Creator put me in a place and time that we needed to talk about our women.”

“We cannot allow any more of our women to be missing in this country,” she said.

“Canada is known as one of the wealthiest countries in the world, and yet, we have to beg for our landfills to be searched.”

According to Statistics Canada, in 2023 about one in four — 26 per cent — of homicide victims were Indigenous, even though they only make up 5 per cent of Canada’s overall population. It’s an overrepresentation of homicides at a rate of 9.31 per 100,000 Indigenous people, which is six times higher than the rate for non-Indigenous Canadians.

Wilson pointed to government policies as a root cause for the MMIWG2S+ crisis, saying the systems “were designed to hurt our people.”

“All of this could have been prevented,” she said. “And we can prevent things today if we just change these systems.”

Melissa Robinson said the advocacy work around searching for their lost relatives has become much larger.

“We’ve pushed hard and have continued because it turned into not only being about our families, now it turned into all of our missing women,” she said. “We used our voices in our platforms to continue that push.”

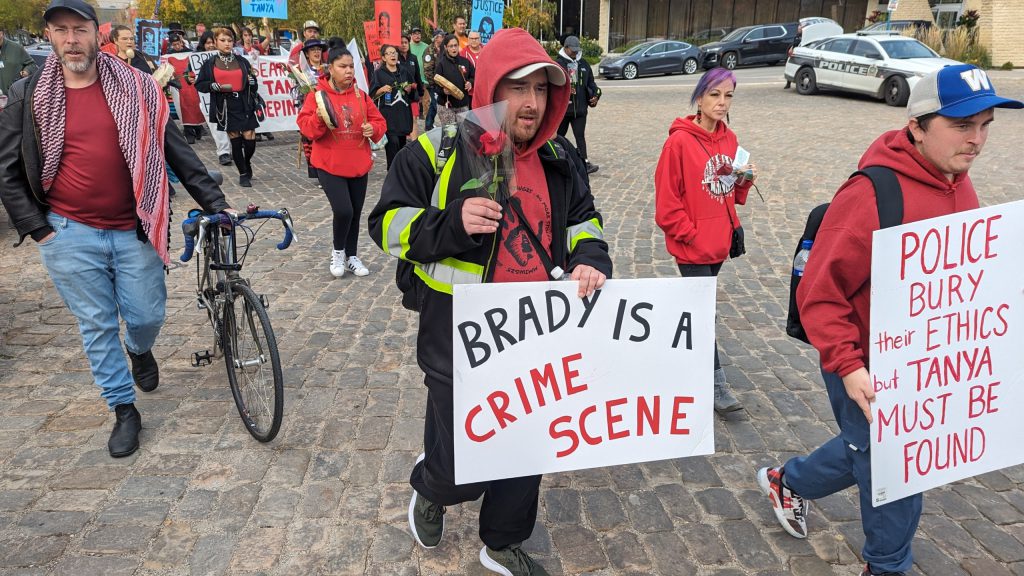

On Thursday, Robinson called for the Brady Landfill to also be searched again.

“We need to go back to Brady, where we know Tanya Nepinak is at, I don’t know how anyone sleeps at night time, knowing that she still lays there.”

In 2011, Nepinak, 31, was last seen leaving her home to buy a pizza slice in “Winnipeg’s” west end and was never seen again. Shawn Cameron Lamb was charged with second degree murder in her death, and two other women, Carolyn Sinclair and Lorna Blacksmith. The charge for Nepinak’s murder was stayed, whereas charges in Sinclair and Blacksmith’s deaths were reduced to manslaughter.

During the six days the police searched for her at Brady, they worked in an area that was intuitively selected by Indigenous Elders through ceremony.

“The six days was an insult. It wasn’t even a search,” Caribou said, in an interview with IndigiNews on February 14 at the Women’s Memorial March in “Winnipeg.”

“Where do you see the heavy machinery? You see guys raking with rakes, there were no shovels, there was no all that masking up,” Caribou added, comparing the smaller scale of the 2012 search to the one happening at Prairie Green.

“It was an insult to offer a family member a monument at a dump, my family doesn’t want to go to the Brady landfill and honour our loved one there.”

Caribou said she suspects that there are other missing people also in the landfill.

“How come they’re not bringing them home when they know there’s human remains there? How can they sleep? I don’t sleep when I think of my niece, I pray nobody’s hurting her, and I still pray that she’s alive, I still continue having that hope.”

Caribou told IndigiNews that she’s been contacting Premier Kinew, asking to revive a search at Brady, but he hasn’t responded.

“We’re put down right away when we report our loved ones missing,” Caribou said. “We need support where we can call somebody and we can go to the police and not do it alone and get bashed and they say, ‘Come back in 48 hours, she’s an adult.’

“The first few hours are the most important, most precious time is from the time they went missing, not years after.”

Similar to an Amber Alert, a public notification system to locate an abducted or missing child or adult with a disability, a Red Dress Alert is being developed in “Manitoba” with input from the Indigenous community. It would alert the public when a woman, girl, Two Spirit or gender diverse person goes missing.

Government support for the alert came after Leah Gazan, an NDP member of parliament for Winnipeg Centre got all parties in the house of commons to declare MMIWG2S+ a national emergency.

The alert is one of the specific actions of the 231 Calls for Justice which came out of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

An online tool tracking progress of meeting the 231 calls for justice was released in January 2025. It showed that six years after the 231 calls were made, that 105 actions were still pending.

“It’s never fast enough,” said Sandra DeLaronde, project lead for the MMIWG2S+ Implementation Advisory Committee, also known as Gigamawenimaanaanig, which translates to “we all take care of them” in Anishinaabemowin.

Gigamawenimaanaanig has done 16 community engagements to develop and move the Red Dress Alert forward. DeLaronde said the two year process was done at “lightning speed” in comparison to how fast the government normally moves.

She is hopeful that more calls to action will become a reality such as a guaranteed livable income, which she said would be a “game changer,” and the creation of an Indigenous ombudsmen’s office.

“We have to lobby for it unfortunately, but I’m confident we’ll get it done.”

In September 2024, the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women delivered a report with 17 recommendations for designing and utilizing the Red Dress Alert.

The report highlighted former CBC reporter Sheila North’s story of Gail Nepinak who was looking for her sister Tanya Nepinak. North is an MMIWG2S+ advocate and former grand chief of the Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak, a northern chiefs’ organization.

“It took 10 days for the police to respond to her. They didn’t respond to her until I did a story on CBC saying she was looking for her. The worst part was when she did finally reach police to talk to her, they told her that she’s an adult and she can go wherever she wants, maybe she went on vacation,” North said.

“That was a big slap in the face for Gail because Tanya only had five dollars in her pocket. She said that our families can’t afford to go on vacations.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

Will you help us tend to the fire?

IndigiNews is launching a fundraising campaign to support our storytelling into 2026