At MOV, Tŝilhqot’in Nation tells the story of a momentous repatriation: ‘We brought back history’

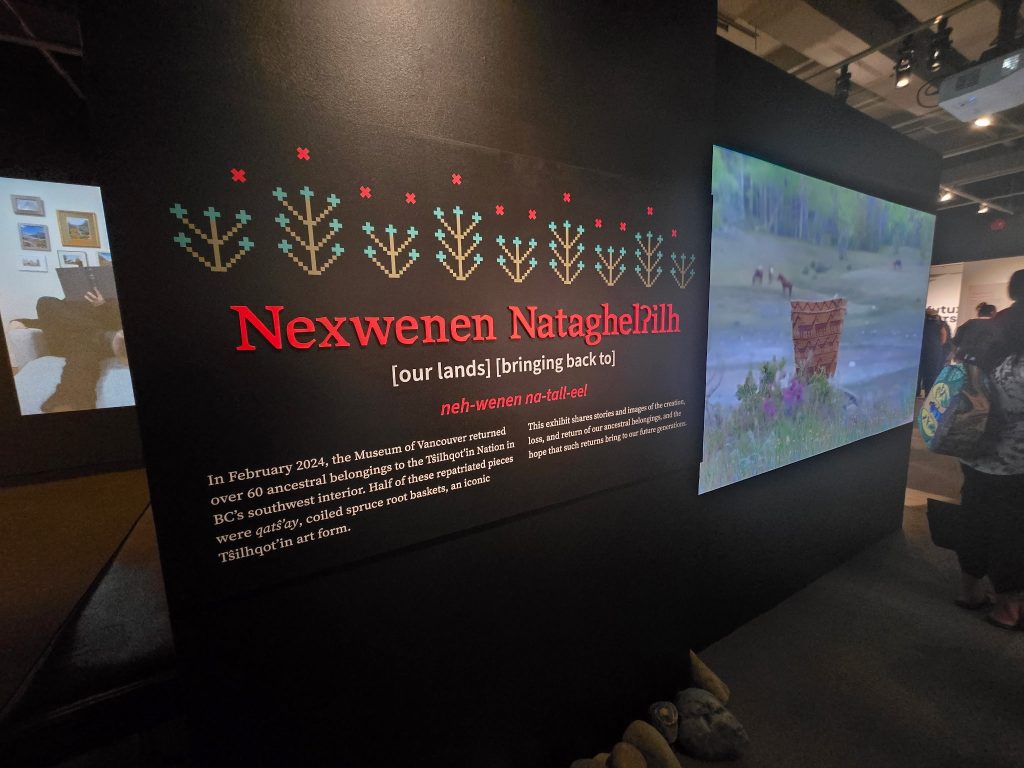

‘Nexwenen Nataghelʔilh’ celebrates the return of more than 60 artifacts, and ‘sets an example’ around how museums can work with Indigenous communities

A new exhibition at the Museum of Vancouver (MOV) showcases a new way forward with the Tŝilhqot’in Nation after the long-awaited return of their cultural belongings.

As part of the larger The Work of Repair: Redress & Repatriation display that opened June 20, Tŝilhqot’in collaborated with MOV to display items that represent their culture, art and history.

MOV’s senior curator of Indigenous collections Sharon Fortney explained that the gallery Nexwenen Nataghelʔilh was a collaborative effort between the two parties and showcases how museums can work with Indigenous communities in a good way.

More than 60 Tŝilhqot’in belongings were returned to the nation from MOV last year — including qatŝ’ay (coiled spruce root baskets) and tŝi-bis (obsidian) stone tools.

Nexwenen Nataghelʔilh includes film, photography and stories detailing the repatriation and its impact, as well as newer cultural items created by the nation specifically for the exhibition.

“I think it’s a really beautiful thing because, you know, we did the work together to repatriate most of the Tŝilhqot’in belongings that are here at the museum. Everything that they requested we returned to them, and then they wanted to continue their relationship with us by doing an exhibition,” Fortney said in an interview.

“It’s really nice, you know, that they felt comfortable asking us to do that work together.”

Nits’ilʔin (Chief) Otis Guichon, a tribal chief with the Tŝilhqot’in National Government, added in a statement that he hopes the relationship “sets an example for other museums around the world.”

“Repatriation is more than bringing our belongings home — it’s connecting to our ancestors, lands, and culture,” he said.

The exhibition’s title Nexwenen Nataghelʔilh translates in English to “we bring them (our ancestors) home to our land.”

“This exhibition represents the change needed in museums around the world — working in relationships of respect, sharing the workload, and telling stories together.”

‘This is also artists of the future’

According to the nation, the return from MOV is the first major repatriation of their belongings, many of which were held in museums or private collections for more than 100 years.

In February of 2024, a group of Elders, Youth, Women’s Council members and former and current leaders visited MOV to bring their items back home.

Loretta Jeff Combs from Tl’esqox and Tl’etinqox, two Tŝilhqot’in communities, has been involved in the repatriation and planning process since the beginning.

Over many meetings, the Tŝilhqot’in Nation members planned the Nexwenen Nataghelʔilh display down to the small details. Jeff Combs noted that, during this process, Elders discussed not wanting the repatriated items to leave the community after they had just returned home — mentioning a Tŝilhqot’in saying which describes walking forward and not going back, which they abided by.

For the exhibition, since they were so purposeful in the energy and feeling behind the pieces, new items were created to ensure that they were made with good intentions.

For example, Jeff Combs noted that obsidian was typically used for weapons and instead of having that energy on display, her partner Peyal Laceese, along with Dakota Diablo, put on obsidian workshops in the community and created obsidian pieces to display.

Along with the newer items, there are two older baskets that are featured.

“This is artists of the past, and this is also artists of the future,” Jeff Combs said.

The repatriation was also filmed and is showcased in a documentary called Qatŝ̂’ay: Bringing Our Spirits Back Home by Jeremy Williams and Trevor Mack, which is part of the exhibition. Jeff Combs explained the significance of the exhibit coming from a Tŝilhqot’in lens.

“We were saying that we wanted to ensure that it had Tŝilhqot’in stories, Tŝilhqot’in language, Tŝilhqot’in knowledge and share it in a way that was our own voice and not through an outsider’s lens,” she said.

The planning group wanted the museum to feel like going into someone’s home — so juniper boughs were included to cleanse the space, and even tree stumps were harvested from the Tŝilhqot’in lands and placed to watch the Qatŝ̂’ay film as if surrounding a campfire to tell stories.

Even when you enter the gallery, a soundscape is triggered, with audio such as rushing water or birds as you’re coming into the gallery, which allows for all senses to be utilized.

Fortney said cultural staff from the Tŝilhqot’in Nation met routinely with the museum over the period of a year to ensure they told the story their way. Fortney noted how the Youth have been heavily involved in the process.

“The young people have been really great, they took a really strong role in the repatriation ceremony,” she said.

Jeff Combs said it was formative watching the Elders and Youth go through the process with the museum together — with a group that Jeff Combs calls her “knowledge keeper crew” taking care of the Elders, including smudging the space for them.

“We made sure that we did our work in a good way, so when the Elders were able to come in, it was just like, all smiles,” she said.

“Just watching the Elders being kind of reconnected with that spirit, and then watching the Youth being able to watch that reconnection, and then see what they’ll bring for the future generations. It was a whole lateral experience.”

She added that the connection to the culture inspired people to think about their own art and how they can evolve and use the teachings from their ancestors.

“It completely changed how I looked at things,” she said.

“It was like, okay, I’m gonna keep moving with this ball but how could I make sure that the policy that I write, or the repatriation that we’re doing or like setting the systems up, how can I make sure that’s true to our people.”

Strengthening cultural connectivity

With a death in the community, only a few Youth and a Tŝilhqot’in chief were able to attend the opening of Nexwenen Nataghelʔilh in late June. They came to the space offering smudging, drumming and singing — which Fortney said echoed throughout the museum — and were able to open the exhibit in a good way.

Jeff Combs discussed the importance of the museum’s partnership and how it can help the younger generations become more aware of their culture and history. She added it will also help future generations to see themselves represented accurately and with pride.

“This is for our children’s children and everyone behind us,” she said.

Jeff Combs’s daughter was along for the journey as she mentions how the knowledge her daughter gets from the culture is just as important as what she would learn in school.

“She’ll learn more culture, she’ll learn more language and that goes for all of our Tŝilhqot’in children.”

As her daughter and another child were interacting with the baskets and other artifacts Jeff Combs was proud to have them in the spaces to learn.

“I was thinking, this is it, they’re going to go home and tell that story when they go back to school, and tell that story when they go back out on the land, and then that story is just going to resonate with all these other Youth,” she said.

She mentioned how at gatherings, when they bring the baskets, the children are the first ones to come up and ask questions.

“We’ve gotten feedback from the Youth being like, ‘I want to be able to go up to the mountain and pick berries.’ And I was like, that’s so cool, because that’s the whole goal of the basket. It’s not just to stare at it in the glass case, it’s to be able to continue to revitalize our ways, but in a contemporary way,” she said.

“I feel like it’s about strengthening our cultural connectivity to these things.”

Even repatriated baskets that are brought out to show the community have been picked by the team. Jeff Combs mentioned how a few Elders viewed some of the baskets as too spiritual and those were brought to sacred sites only.

She described how an energy comes through the artifacts — deemed to be ancestors — and the artifacts brought to gatherings and events are more “warm” and give off an energy of sharing and teaching.

“When you think of repatriation, it’s more than just bringing artifacts back. And we try to step away from using that word, and we look at them as ancestors,” she said.

“We didn’t just bring back a bunch of baskets. It was like we brought back history and storytelling, and we brought back a spirit that we essentially — I say, in our Qatŝ̂’ay video — we gave breath back to these baskets, and we have to do that and continue to honour that in every way.”

Connecting with ancestors

When discussing the exhibition and artifacts that have already returned home, Jeff Combs noted how people are drawn to different pieces.

“I noticed a lot of people gravitate to what they feel like is on the baskets,” she said.

“You’re able to look at it and then depict it in your way, and then someone could have a completely different perspective, but they’re still resonating with each of it.”

Even the group who have been involved in the exhibit and repatriation process have differing ideas of designs on each basket.

“It’s kind of extra special that we aren’t able to fully depict what they mean,” she said.

She added that while there are universal images that can be deciphered quickly such as lakes or mountains, there are still unknown designs which anyone can give ideas for as possibilities.

“Everybody’s heard so that when they connect with these ancestors, essentially, it’s how they perceived it, and we’re never going to tell them anything different. It’s like, this is yours, because it belongs to the people,” she says

To Jeff Combs, this repatriation and collaboration is just the beginning, as she calls it, “a living legacy” for not only the Tŝilhqot’in Nation but all Indigenous communities who are looking to bring their artifacts home as well.

“A lot of Indigenous communities across Canada are starting to dip into [repatriation]. And the future is essentially all Indigenous artifacts deserve to go home to their communities and it’s something that each of us can learn from and be proud of,” she said.

She added that the knowledge becomes greater through relationships and sharing with other communities.

“It has to be collective, and it has to be together, even if we are from different nations,” she said.

“Imagine what we could learn from each other, and imagine what artifacts we could take back from the colonial institutions when we have that power in numbers and that power and strength and culture and everything.”

Fortney added that any exhibition about an Indigenous community should involve a good relationship, “so it doesn’t really matter whether or not their belongings are in your museum, because if you have a working relationship, if they want to, they’ll loan them back to you.”

“The work we’re trying to do is about correcting past wrongs and working in a new way,” she said.

Expanding the knowledge

Fortney explained that along with the exhibit comes programming, including the Repatriation Monologues and the MOV website says includes “individual reflections and shared dialogue” from a panel exploring “the emotional and cultural impact of repatriation, the challenges of institutional change, and the ongoing responsibilities museums face in redressing colonial harm.”

Jeff Combs and her chosen sister, Chantu William, received a grant for workshops at the MOV which they hope will allow them to grow relationships with local Indigenous communities as the museum is on the unceded, ancestral territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

“Although those are our things, that’s not our territory. So we have to make sure that we acknowledge the people whose territory we’re on, in a good way, being like, we also stand in solidarity, and we respect the lands that we’re on, and we respect that the belongings are in your territory,” she says.

Jeff Combs is strengthening her connection with the museum process as she also received a grant from the First Peoples Cultural Council.

She notes that her repatriation work was chosen for her and now she finds the work to be inspiring.

With the grant, she will be working alongside Fortney at the MOV and also with museums in Indigenous communities like the Nisga’a Museum and the Haida Gwaii Museum to learn their processes and bring that knowledge home to help create a culturally appropriate space in the Tŝilhqot’in to display their artifacts.

Her work is just the beginning as she hopes to share her knowledge with her community and create someplace meaningful for the artifacts to return to once repatriated from museums.

“It’s a collaborative effort. It can’t just be, you know, one person, it’s gonna take 1,000 voices and 100 hands, but we’ll be able to get it done,” she says.

Fortney said she has heard from many people about the possibilities that can come from the museum’s willingness to share and educate. High school teachers are asking about an educational program and that sharing and expanding beyond the museum is what Fortney had hoped for.

“I think that this is a really powerful exhibit for connecting people in that way,” she said.

To her, Nexwenen Nataghelʔilh is healing, as it showcases the communities getting their belongings back which returns the knowledge back to the people.

“I think educating the public about repatriation is really important, because I think it’s becoming more prevalent. There’s more and more communities who are reaching out. They’re looking for their belongings, and they’re wanting to bring them home. And it looks different in every community,” she said.

“So it’s not necessarily that you have a long, lasting relationship in an instance like that, but you just want to make sure that you’re leaving with a positive experience, you know, and that the door is open to further conversations or outreach.”

Nexwenen Nataghelʔilh will be on display until April 2026 and is free for all self-identifying Indigenous people.

Editor’s note: This is a corrected story. A previous version erroneously stated the exhibition would be on display until April 2025 — in fact it is 2026. We apologize for the error.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

After Indigenous teen’s stabbing, his family says the system failed to stop his bullying

Foster parents in ‘Courtenay, B.C.’ speak out after a string of alleged incidents targeting them and their 16-year-old foster son, as they wait for trial

-

‘We all share the same goals’: Tŝilhqot’in and syilx foresters learn from each other

Nk’Mip Forestry and Central Chilcotin Rehabilitation visit their respective territories, sharing knowledge and best practices