The landfill blockade is dismantled, but the push to search for MMIW continues

Writer Viv Ketchum asks why the Manitoba government refuses to offer the families of slain Indigenous women closure, honour or respect

Content warning: This story includes content about “Canada’s” genocidal epidemic of MMIWG+, and also deals with grief and loss. Please look after your spirit and read with care.

July is a difficult month for me — it’s my late son’s birthday month. He was born on a hot summer afternoon, and I never knew I could love so hard and so openly as I did as a first-time mother.

Never did I imagine then that I would have my son with me for only 24 years. He passed away on March 7, 2011, after developing a rare brain tumour. As difficult as that was — I had the gift of saying goodbye to him. By his bedside. At his wake. At his funeral.

That process of saying goodbye to my son was a necessary healing step for me and my family. I can’t even imagine how much harder things would have been had I not been able to have that closure.

Those thoughts stayed in my mind while I was attending Camp Morgan, a blockade at the entrance of the city-owned Brady Road landfill on the outskirts of Winnipeg, earlier this month.

Although the camp had been set up since late 2022, it escalated to a blockade in early July after the province announced it wouldn’t support a search of the privately-owned Prairie Green landfill, located north of the city.

Although the current push is to enact a search of the Prairie Green facility, many activists and supporters also want to see a search of the Brady Road landfill.

The family members who are fighting to have the landfills searched for the remains of their loved ones haven’t had an opportunity to say goodbye. The community has rallied around them in order to try to fight for a proper investigation.

I have been at Camp Morgan when it was very cold outside, with wet ground inside of the main tent. Cots and food were piled up inside while propane tanks were being used to keep the heaters going.

There was a small wood stove, but the propane heaters were needed to keep the chill out. A Sacred Fire was also kept burning, and the smell of sage lingered in the air.

The camp continued on as the months became warmer and there was still no promise of a search. Bright red dresses were hung up on the fence, reminding us why the camp was there.

My first time at the camp, I was overwhelmed with an immense feeling of sadness when I saw the landfill. These women need to come home.

There are four women whose deaths have now been tied to alleged serial killer Jeremy Skibicki. It has been close to a year now that their family members have been fighting for proper landfill searches.

The remains of Morgan Harris and Marcedes Myran are both believed to be at the Prairie Green facility. Rebecca Contois’s partial remains were found in the Brady Road landfill last June.

Linda Mary Beardy’s body was discovered at the Brady facility in April, but police said it was not a homicide or related to Skibicki. Another believed victim of Skibicki is yet to be identified and being referred to as Mashkode Bizhiki’ikwe or Buffalo Woman.

These are just the names we know about. There could be any number of bodies left in these landfills but there’s no way of knowing without a proper search, so the community is left to speculate.

Manitoba Premier Heather Stefanson has said searching the Prairie Green landfill is too expensive and that there would be health risks to the workers. Meanwhile, other organizations have stated a landfill search can be done safely. Despite the overwhelming public demand, Stefanson refuses to mobilize a search.

Shortly after the road to the Brady landfill was blockaded, the City of Winnipeg filed for an injunction as it sought to have Camp Morgan dismantled. On July 14, I sat nervously in the court with other supporters as we awaited the judge’s decision on whether the injunction would be served.

The courtroom was half-full of Indigenous women and some family members of Morgan Harris and Marcedes Myran. I could see some media on the other side of the room, and other reporters outside the court building with cameras and microphones by the entrance.

More supporters were also waiting outside for news of the judge’s decision. A group of women in ribbon skirts stood in a half circle to drum and sing. The atmosphere was tense in the courtroom and outside the building.

I sat in the back of the courtroom and heard the judge’s words that he was going to approve the injunction. I saw another supporter run out of the courtroom, upset, and I also left without waiting to hear the rest of the decision.

I let the other supporters waiting outside of the courthouse know the bad news. I then phoned protesters to inform them that the injunction was approved.

I learned that the police would be enforcing the injunction at 6 p.m. People at the courthouse began to rally for support to gather at the Brady landfill that evening.

I headed down to the landfill that evening as more information about the injunction began to come out on social media. The injunction was to have the blockade cleared, but the protest was considered legal on a temporary basis.

As I and the other supporters pulled up at the landfill, there was a long line of cars that had formed along the road.

Groups of people were walking or standing by the front of the road. Media were also lined up with their cars and trucks. Shortly after I got there a city worker came to place a copy of the legal injunction on a placard by the side of the road. It was quickly knocked over by protesters into the ditch.

Thirty minutes later a police liaison officer came by to hand over a copy of the injunction to one of the main protesters. The crowd of supporters and media gathered around the officer as he stood calmly across from the protester.

There had to be about 50 or more supporters at the front of the blockade. The officers left shortly afterwards, but most of the supporters stayed throughout the evening.

About a week later, the large group of supporters had left the Brady landfill blockade. The police did finally show up to take down the blockade without any incidents or anyone being arrested.

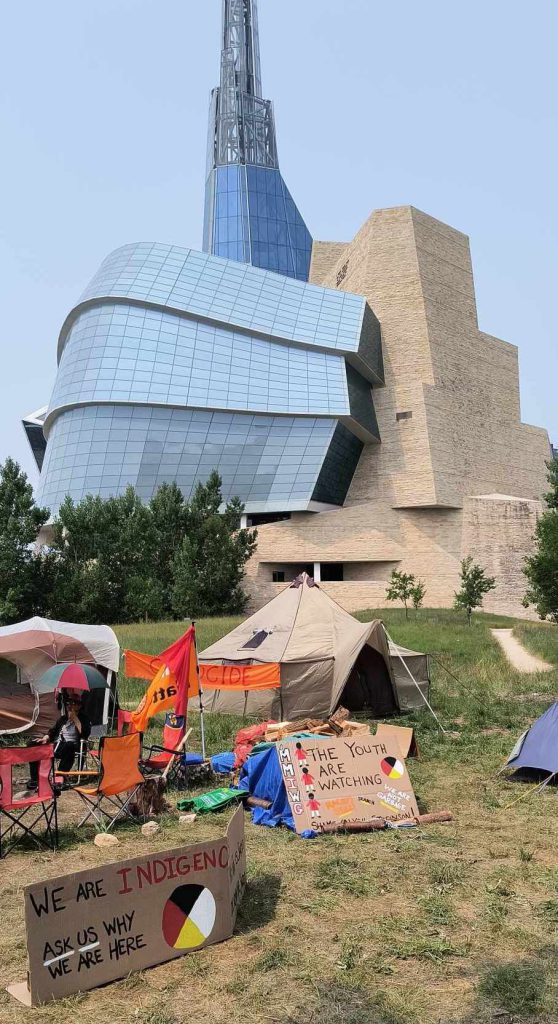

They allowed the camp protesters to remove any personal items on the road. A wigwam and the two tipis were allowed to remain — they were not subject to the injunction. The main supporters decided to set up a second camp at the The Canadian Museum for Human Rights, with permission.

This second camp was named Camp Marcedes, after another of the women believed to be buried at the landfill. There are now two camps set up: the original Camp Morgan and the new one at the museum.

Despite the setback of the injunction, the camps have overall been a success because their message has only gotten stronger, and there’s been escalating support from people who want a landfill search so these families can have a chance to bring their loved ones home.

The family members of these women who have not yet been found deserve to have their loved ones brought home for burial and ceremony. They have the right to say goodbye in a dignified manner. They deserved to have their loved ones buried in a respectful spot.

A landfill is not a graveyard. Not a place for our Indigenous sisters. The family members deserve closure and a chance to complete the grieving cycle.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

Pimicikamak faces long road to repair after havoc-wreaking power outage

As the military is ordered to help the northern ‘Manitoba’ Cree community, AFN leader says ‘emergency deployments cannot become the standing response to chronic infrastructure gaps’

-

Why aren’t there more Indigenous foods in ‘Canadian’ grocery stores?

Indigenous foods are varied, delicious and plentiful — but getting them to customers can be a challenge for small producers