Two-Spirit trans youth on reclaiming his identity

Leo Isaac will share his story through RavenSPEAK Emerge, a virtual showcase of Indigenous youth storytellers

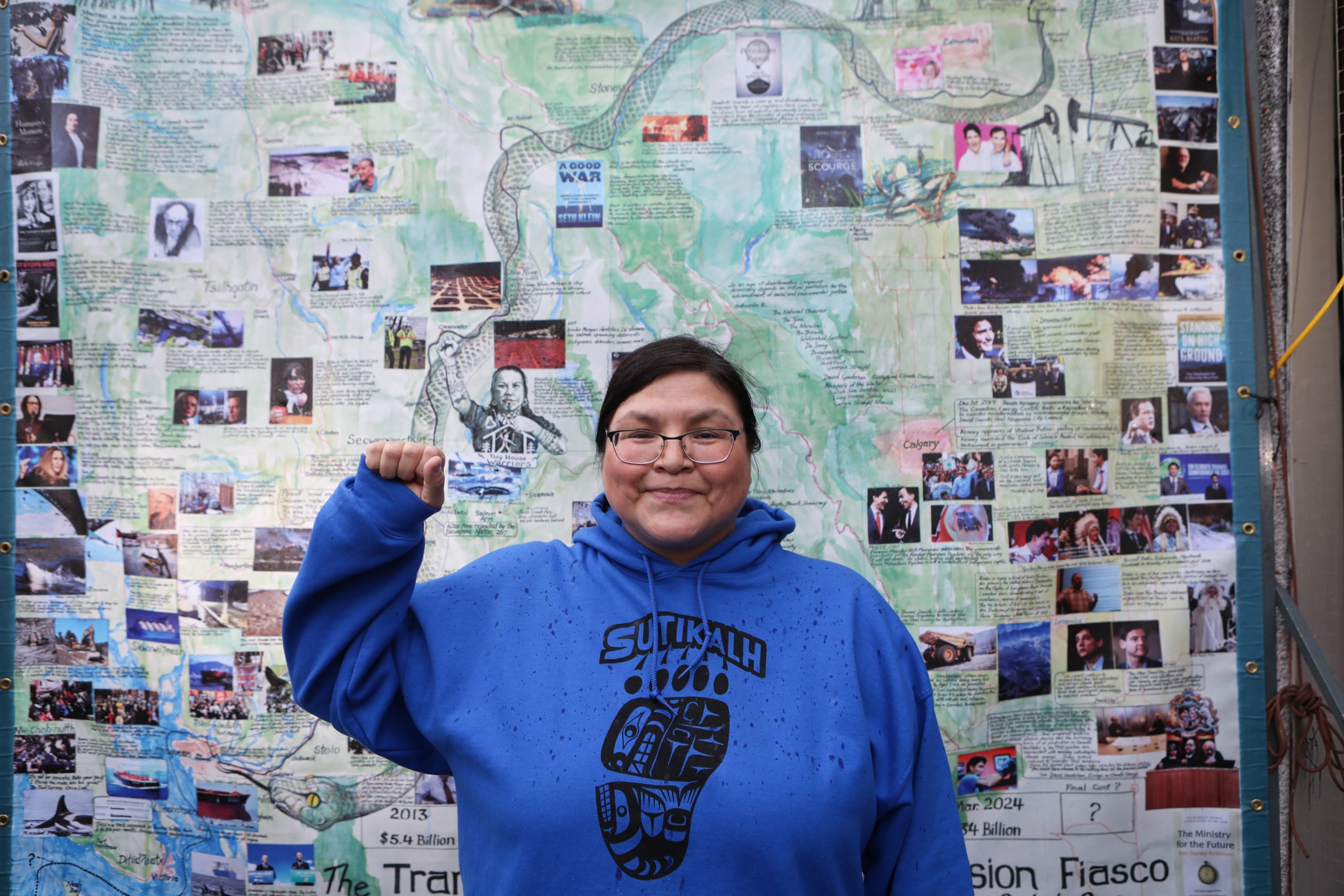

Leo Isaac is looking forward to taking the stage on May 14 as one of 11 young Indigenous storytellers from across co-called Canada, as part of the RavenSPEAK Emerge program.

“I’m just really hoping that my voice helps lift people,” says Isaac, who identifies as trans, a second-generation survivor of the Sixties Scoop, and a member of Nak’azdli Whut’en First Nation.

The RavenSPEAK Emerge program supports youth to bring forward, “their gifts, medicines, wisdoms, knowledges, traditions, values and ways of being,” according to the program’s website. It marks a collaboration between the Indigenous LIFT Collective, a not-for-profit, and the Raven Institute, which is co-led by Métis mother-daughter duo, Kiana Alexander-Hill and Teara Fraser.

Isaac was introduced to RavenSPEAK through a friend and he says he saw the opportunity to help “people through storytelling.”

After sharing a meal and smudging, Isaac spoke with IndigiNews about how taking time with his story has helped him to heal and develop empathy for his mom.

Finding Leo

Isaac remembers well the day he told his mother he was trans. He was 24, and he says he’d been building up to the moment for a long time.

“I was watching more people online and reading their experiences, and I knew, okay, this is just who I am,” says Isaac. “There was just no going back.

“I began coming out to everyone [in 2016], and my mom was the last person I needed to tell before I came out on social media.”

Then on June 12, 2016, at the LGBTQ2S Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, 49 people were killed in an attack described by The New York Times as “the worst mass shooting in U.S. history.”

Isaac says he felt called to come out to his mom when the victims’ names started rolling out and he realized many were trans.

“A lot of the families were using their birth names,” he says. “[I felt] In that moment that if I didn’t honour them by stepping out and honouring my true self then I was just doing a disservice.”

So on June 13, the day after the tragic shooting, he decided to tell his mother, in an email.

“I literally held my breath and got a text message an hour later,” he says. “It just said, ‘I still love you, but I need some time,’ and that was it. We didn’t talk for six months after that.”

“It was tough. It’s tough to have family [members] that don’t understand you, or aren’t ready to learn,” he says, adding that he was raised as part of a church-going family.

“It was just a lot of misconception of what it meant, and what it meant for my soul.”

Asked about the moment he and his mom resumed speaking, Isaac says the shift in their relationship happened naturally.

“She was able to see that I was truly happy,” he says. “I know that’s what any good parent wants for their kids, so it was a slow coming around, but there was an understanding that really happened.”

Now Isaac says his relationship with his mother is “so different.”

“When she calls me her son my heart soars. It feels so good, and she also defends me fiercely against anyone,” he says.

“She points out rainbow everything. She’ll say, ‘Oh look, look! It’s a rainbow flag!’ And I just say, ‘Aww, Mom.’ It’s just so precious and she’s doing her best to be so accepting.”

Reclaiming kinship and his Indigenous identity

“I didn’t even want to step into my Indigenous identity until I felt at home with Leo,” he remembers.

“I finally was able to not only just have the words and language to reclaim those emotions and that disconnect I have been feeling, but also just [to be] able to step out so unapologetically — there was something so beautiful about it,” he says.

A few years later, in 2020, Isaac says he recognized that he was in a place to reclaim his whole being, as he was born to be, and he began the journey of reclaiming his Indigenous identity.

“I started to dig into my roots and who I am,” he says. “I didn’t even want to step into my Indigenous identity until I felt at home with Leo. There was still something missing and it was just that connection to the community.”

Isaac says this journey has led to a different perspective on his mom and his childhood.

“I always knew my mom was a Sixties Scoop baby, but I have more empathy and understanding when it comes to her parenting styles and how we grew up, and the lifestyle that we had,” he says.

He says whether his mom realizes it or not, she carries knowledge from the Ancestors, and she has passed it down to her children.

For example, recently Isaac’s been struggling with everyday tasks, “even just doing my dishes.” His sister came over and said, ‘‘If I do your dishes, will you make bannock?”

“That was such an Indigenous way to do things,” he says. “We are engaging in these Indigenous ways of being without even knowing it.

“Just that reciprocity in caring for one another, that she gave what she could and I offered what I could,” he continues, “that’s a big teaching for me, offer what you can and ask for what you need.”

Creating sacred spaces

Isaac says after feeling displaced for so long, he’s working to create spaces in his community where people can feel they belong.

“It’s so important to have those safe spaces and those sacred spaces, so [I’m] creating that wherever I go.”

As he prepares his seven-minute talk for the RavenSPEAK Emerge event, he hopes to leave a lasting message for others who may be struggling to reclaim their identities.

“The point I would like to get across is to live loud, and live proud and never let the fear of your potential stop you from going after your spirit’s calling,” he says. “We need our Indigenous youth to step into their roles, and reclaim those roles as Two-Spirit beings.”

Author

Latest Stories

-

Inquest continues into Winnipeg police shooting death of Eishia Hudson, 16

Non-adversarial probe of teen’s death cannot assign blame, but family and First Nations hope it will recommend meaningful ways to prevent similar police shootings