‘NDN Giver’ exhibition showcases the art — and responsibility — of potlatching

From mugs to prints, masks and blankets, a new Bill Reid Gallery display celebrates the ancient Northwest Coast gift-giving tradition

It began when Amelia Rae was in her auntie’s kitchen helping herself to a hot drink.

She’d been there countless times before. But as she looked at a shelf loaded with mugs — stacked deep with so many different sizes, shapes and colours — she suddenly realized all of them had been gifted at potlatches.

“I had to take a moment,” said Rae, a member of the Tsiits Git’anee clan from Old Massett in Haida Gwaii.

“Oh my god, that’s like hundreds of mugs.”

In that moment, Rae realized something else.

“This is so much more than a vessel for coffee and tea,” she said.

“So much more responsibility comes from something that’s gifted at a potlatch, no matter how big or how small or how grand something may be.”

Accepting a gift at a potlatch, she explained, is to carry forward what its recipient witnessed there — and to remain accountable to the host family for future generations.

Such gifts are not transactional — they’re relational. They hold communal memory, and an agreement with one’s community.

“It was a realization of, ‘Oh, this is way more than just a simple mug.’”

The idea stayed with her long enough to become NDN Giver — Rae’s first solo exhibition as curator at the Bill Reid Gallery, located on xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and səl̓ilwətaɬ territories in downtown “Vancouver.”

Her show, which celebrates the living law of the potlatch, runs until Feb. 22, 2026.

The potlatch is a central system of governance, ceremony, and social life for many Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast.

The important community events are where rights, titles and responsibilities are publicly affirmed and carried forward through feasting, ceremony, and gift-giving.

“Canada” banned potlatches and other ceremonies for nearly 70 years, until 1951 — part of colonizers’ attempt to eradicate Indigenous systems of law and governance.

But thanks to the resilience of kinship networks, some ceremonies continued underground, quietly, allowing ancient laws to survive.

Today, the potlatch continues to be a living practice of Indigenous law and sovereignty — while adapting to new contexts that affirm the values of ancestors, and the mutual obligations that connect families, clans, and nations.

Advice from relatives shaped the exhibition

IndigiNews met Rae last month, during her last week curating the gallery, before returning to her homeland of Haida Gwaii.

Rae has been around cultural heritage work for most of her life.

Her mother is Sdahl K’awaas (Lucy Bell), who for years worked at the Royal BC Museum in “Victoria,” and is acclaimed for decades of leadership repatriating Haida Nation’s ancestral belongings.

Because the pair moved frequently between places and institutions, as the winds carried them, “My mom calls me her ‘kite,’” Rae said.

Following in her mother’s footsteps, Rae has worked at a number of museums: an internship at the Museum of Anthropology on xʷməθkʷəy̓əm territory; the U’mista Cultural Centre in ‘Ya̱lis (“Alert Bay”); and the Haida Gwaii Museum.

But this is her first time curating a full exhibition at a gallery.

More than two years before NDN Giver opened, she recalls pitching the idea when she started working at Bill Reid Gallery.

At the time, Rae felt overwhelmed at the thought of turning her concept into something physical, since a potlatch is not a singular or simple theme to interpret — it’s a living governance system, and it’s deeply personal.

“I could have put anything in there,” Rae recounted, “so it felt like a mental breakdown.

“I called my mom. I called my aunties. I asked the community who have been potlatching their whole lives.”

Their guidance, she said, helped shape the exhibition she created, just “as it has shaped my life.”

On the mezzanine level, the exhibition wraps around two wide walls, featuring works by Haida creators including Glathba (Charlie Brown), K.C. Hall, and Skil Jaadee White.

Rae included them because they are artists and friends who’ve dedicated their lives to potlatch, and to the responsibilities they carry for their communities.

Her choices of artists, she said, “were all no-brainers,” because they were the community giants she “really wanted to uplift.”

She also featured is work she created, and other items family members gave her.

Visitors to NDN Givers first encounter the playful display of Rae’s auntie’s mugs.

That auntie, Candace Weir, is married to Haida master artist Kihl ‘Yahda (Christian White), whose solo exhibition is on view downstairs.

Then, viewers’ attention is drawn to a prominent carved box — a collaboration between Híɫzaqv cousins Glathba (Charlie Brown) and K.C. Hall.

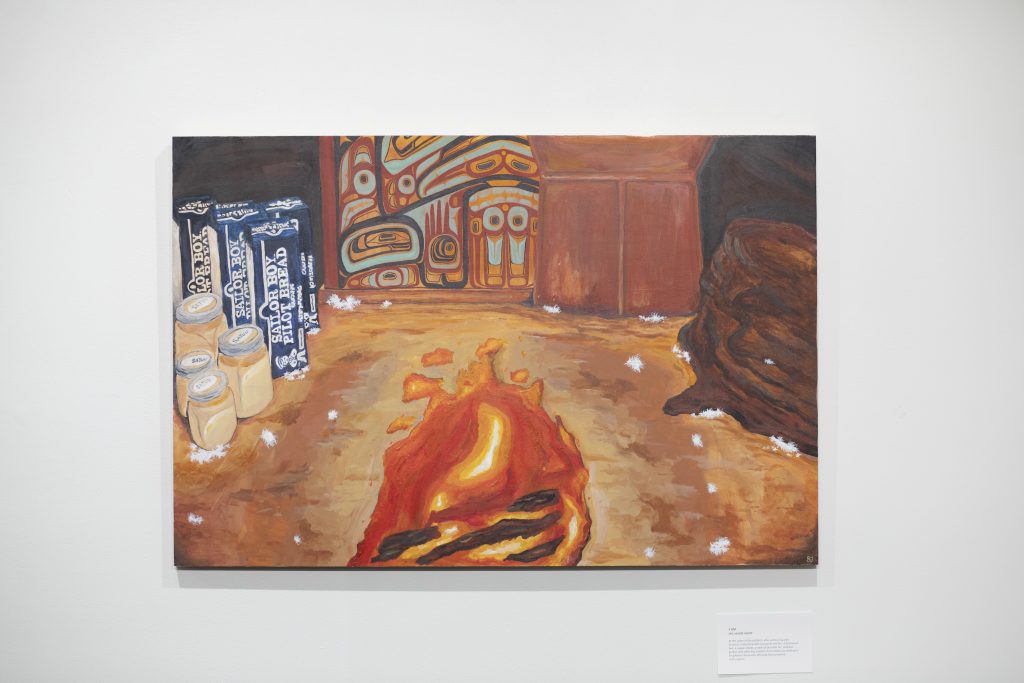

Nearby hangs 3am, a painting by Rae’s closest friend Skil Jaadee White, from Haida Nation’s Yahgu Janaas clan.

The work depicts the late hour when potlatch gifting often begins.

At that time in the ceremonies, the host venue’s floor is covered with material wealth waiting to be distributed.

Oolichan grease, sea otter pelts, copper shields — and even boxes of Sailor Boy Pilot Bread from “Alaska,” a brand of hardtack biscuits especially coveted on Haida Gwaii.

“And if anybody knows where they’re sold,” Rae half-joked about the hard-to-find product, “then please let me know.”

Another work displayed in NDN Giver references a potlatch hosted by Sdahl K’awaas, an ancestor of Rae from the village of Yaan.

Sdahl K’awaas was a powerful woman within Haida Nation’s matrilineal society — so successful that she was able to not only build a new house and raise a pole, but also host a massive potlatch.

That event is remembered for its towering stack of 1,000 blankets for guests, as well as pelts, spoons and potatoes from her own harvest.

As Rae tells the story, after everyone had received their gifts, Sdahl K’awaas held up the very last blanket — which was little more than a rag — and offered it to her own husband, “for all the work you did,” Rae said.

“That cheeky side” of Haida matriarchs, Rae said, smiling, is “very evident in Haida women today.”

Other gifts: trade beads, necklaces, prints

Rae’s NDN Givers exhibition also showcases strands of trade beads and necklaces — some of them very old, and others created more recently, including by Rae herself and her aunties and relatives in “Alaska.”

Before a potlatch, it’s common to see people stringing hundreds of such necklaces to be given away, Rae explained.

Haida territory extends into southeast “Alaska,” and Rae noted that she has many family connections in Tlingit communities there.

Within families, trade beads have been passed on through generations, first via Russian trade, and later from other sources, and they are highly prized.

Part of curating the exhibition, Rae said, was building trust to borrow such important personal and family items. Trade beads are not just objects, but key pieces of family history.

“It was a big ask,” she said, “but everyone just said, ‘Of course,’ which I’m really grateful for.”

The exhibition’s final section is filled with prints, another common form of potlatch gift that has endured for generations.

On Haida Gwaii, people who have attended many potlatches likely have a large collection of gifted painting prints.

Rae’s mother, she said, “gets kind of spunky when she’s given another print,” because her home is already overflowing with things.

The works on display in this part of NDN Givers include a print from the 1999 memorial potlatch for Rae’s great-great-grandmother on her father’s side.

Others were created by family members more recently, including a piece by her grandmother’s brother, given away at a potlatch earlier this year.

With the Bill Reid Gallery exhibition underway for the next four months, Rae returned home to Haida Gwaii — this time, she insisted, for good.

Her homecoming came nine years to the day after she left, Rae said, “like closing a circle.”

“And what a high note to end on,” she told IndigiNews, adding she’s “trusting in the universe that something will come my way.”

Her only plans now include spending time with her niece, who’d been “anxiously awaiting” her return, and having “lots of cups of tea” with her grandmother.

And chances are, some of those will be sipped from a potlatch-gifted mug so common in Haida kitchens.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

After Indigenous teen’s stabbing, his family says the system failed to stop his bullying

Foster parents in ‘Courtenay, B.C.’ speak out after a string of alleged incidents targeting them and their 16-year-old foster son, as they wait for trial

-

‘We all share the same goals’: Tŝilhqot’in and syilx foresters learn from each other

Nk’Mip Forestry and Central Chilcotin Rehabilitation visit their respective territories, sharing knowledge and best practices