‘Not our border’: How a colonial line shapes Tlingit lands — and my own ancestor’s role in it

A canoe trip across the ‘U.S.-Canada’ boundary reminds Mike Graeme of colonialism’s legacy — as he follows the path of his surveyor great-great-uncle

Sitting beside me in a 10-metre-long fibreglass canoe painted with Tlingit designs, Ben Coronell explains why he’s joined this journey paddling from “Canada” across the international border southwest to Dzántik’i Héeni (“Juneau, Alaska”).

Coronell, who is Tlingit from the “U.S.” side of the boundary, says he set out with the Taku River Tlingit — or T’aaḵú Ḵwáan — on the trip’s second day hoping to reconnect with his relatives in “Canada.”

“120 years ago, we didn’t think in terms of borders,” he says.

The canoe, which carries us and six others, features on one side Tlingit designs characteristic of Chilkat weavings.

On the other side of the vessel are a raven and wolf, representing Tlingit moieties — two umbrella lineages under which the nation’s clans and houses are organized.

Dozens of Tlingit communities stretch from northwest “B.C.” into the “Yukon” and “Alaska.”

“We have always been one family,” Coronell explains.

As a drizzle of rain falls on us, I feel the weight of history rippling across the waters we travel.

While the Tlingit participants around me journey to reconnect with each other and their ancestral waters, this trip has made me reflect on my own family’s colonial history — one that directly shaped the border now cutting Tlingit lands in two.

In 1904, my own great-great-uncle helped demarcate this international boundary dividing “Alaska” from “B.C.”

I travelled up north because I wanted to trace my ancestor’s journey — to see for myself what his surveying quest may have entailed.

And I hoped that coming here, 120 years later, would allow me to witness the enduring impacts — and to learn how I can support ongoing resistance to colonial oppression.

‘This whole area is our home’

Our canoe journey begins at the confluence of the Taaltsux̱éi (“Tulsequah River”) and T’aaḵú Héeni (“Taku River”) in “B.C.,” later crossing the border into “Alaska.”

Our destination is Dzántik’i Héeni (“Juneau”) for Celebration, a cultural gathering of Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian people hosted every two years by the Sealaska Heritage Institute.

On the first of the four-day trip, a small group of us makes our way down the swift-flowing T’aaḵú Héeni, passing a faint line of cut trees marking the international boundary.

The border’s straightness seems unnatural, carved into a landscape otherwise curved with rivers and glaciated valleys — the Tlingit Nation’s homelands.

“For us, that’s an artificial border, that’s not our border,” says Rodger Thorlakson, lands and resources manager with Taku River Tlingit First Nation, who sits a couple seats behind me in the canoe.

The community is located in Áa Tlein (“Atlin”), a remote First Nation of roughly 400 people, just 50 kilometers south of the “B.C.-Yukon” boundary, and about 75 kilometers east of “Alaska.”

“That’s a border that we didn’t have any say in,” Thorlakson says. “This whole area is our home.”

‘Claiming territory for the purposes of empire’

It was England’s chief justice who determined the final route of the international border, a decision made far from Tlingit territory.

I read about this boundary-mapping project just days before joining the canoe journey, in a memoir written by my great-great-uncle Alexander Gillespie.

I pored over his 1954 autobiography, Journey Through Life, and any other writings I could find by him, wondering what his journey to Tlingit homelands was like, and what brought him there.

Gillespie was among the first groups of “Canadian” surveyors tasked with officially marking the “B.C.-Alaska” border in 1904.

I wonder: What conditions brought him to these Tlingit homelands? And how did Tlingit in his day see these surveyors?

My great-great-uncle was born on June 4, 1880 on Cook Street in “Victoria, B.C.” — Lekwungen homelands — just nine years after the province joined Confederation in the new country of “Canada.”

He grew up steeped in colonial society and surrounded by its notorious figures.

As a child, he remembered Matthew Begbie, the first chief justice of the new province’s Supreme Court, hunting ducks at the end of the street near Dallas Road.

Begbie has been dubbed the “hanging judge” for infamously sentencing six Tsilhqot’in chiefs to death in 1864.

And among Gillespie’s other neighbours was the brutal colonist Joseph Trutch, “B.C.’s” first lieutenant governor, who described Indigenous peoples as “utter savages” and whose “Indigenous land policy was too harsh even for Britain’s colonial office,” according to Knowledge Network’s British Columbia: An Untold History website.

Gillespie and his brothers would cross Trutch’s fields to play in the old Hudson’s Bay Company buildings.

“We used to climb up on the rafters and play ‘wild Indians,’” he recounted. “We used to think we could see old arrow marks in the logs, and in our imaginations could picture battles with the Indians.”

When he was 24, Gillespie applied to join the northern border-survey parties being deployed to officially delineate the new international boundary, under the supervision of surveyor C.A. Bigger, with “Canada’s” Dominion Land Survey.

“I was greatly pleased when I was appointed to a party under C.A. Bigger,” he wrote in Journey Through Life.

Creating and delineating borders was crucial to states’ colonial projects worldwide, explains Harsha Walia, author of Undoing Border Imperialism and Border and Rule.

Walia calls borders a crisis of displacement and immobility, adding that drawing international lines divides people and communities — all aimed at enforcing a racialized system of global subjugation, she tells IndigiNews.

“Borders are fundamentally about marking territory,” she says, “and claiming territory for the purposes of empire and imperialism … capitalism and colonialism.”

In Gillespie’s era, the unearthing of gold in “Yukon” — sparking the “Klondike” gold rush and its wave of some 100,000 miners to the region — added urgency to mark the boundary more precisely and permanently.

At the time, as the “U.S.” wanted to secure its own access to mineral resources, “Canada” hoped to ensure seaport access to “Yukon’s” gold fields, a goal it never actually achieved.

‘Into unknown parts’

Setting off from “Victoria, B.C.” in May 1904, Gillespie travelled by steamship to Shg̱agwéi (“Skagway, Alaska”) and then to Deishú (“Haines”).

He then took a Tlingit dugout wood canoe up Jilḵáat Héeni (“Chilkat River”) to the village of Tlákw Aan (“Klukwan”).

In that village, Gillespie saw several nearly-14-metre cedar canoes owned by a chief, as well as a series of cannons mounted on the riverbank, which the Tlingit had taken from Russian explorers to fortify their defenses against colonizers.

It is by following Gillespie’s route — from Deishú to Tlákw Aan — that I embark on my own trip in May this year.

My journey brings me to the Jilkaat Kwaan Heritage Center, where I meet a relative of renowned Chilkat Elder Joe Hotch.

He says that the Tlingit have their own histories of resistance, ones often left out of colonial history books.

Hotch once recounted that the Canadian Army attempted to set up their border camp near Tlákw Aan (“Klukwan”) in 1902. But the local community resisted.

“The Klukwan Chief said … if you don’t move in two days then we’re going to declare war on you,” Hotch explained. The colonizers, he said, promptly left.

The Canadian Army then pushed their provisional boundary farther up the valley to Pleasant Camp, where Gillespie’s crew would reach two years later.

From Tlákw Aan, Gillespie and his self-proclaimed “cosmopolitan crew” of English, Scottish, and French-Canadian settlers soon reached the Chilkat Tlingit grease trail that would lead their border party up to Pleasant Camp.

I wonder if my uncle ever considered the long history of this trail — for generations part of an extensive Chilkat trading network to Athabascan communities in “Yukon’s” interior.

Gillespie referred to the trail as the “Dalton Trail,” named after colonial pioneer Jack Dalton, who usurped Tlingit control of the trading route in the 1890s — and set up henchmen along the trail to help him profit from gold rush traffic.

According to Gillespie, Dalton “was a man full of energy and the sort to develop a wild country such as this,” invoking the widespread colonial narrative that Tlingit homelands were an uncivilized place to be “tamed” by settlers.

Gillespie’s crew hired a wagon from Dalton and took the trail up to Pleasant Camp — at the time a Royal North West Mounted Police barracks — where the border-survey party camped for the season.

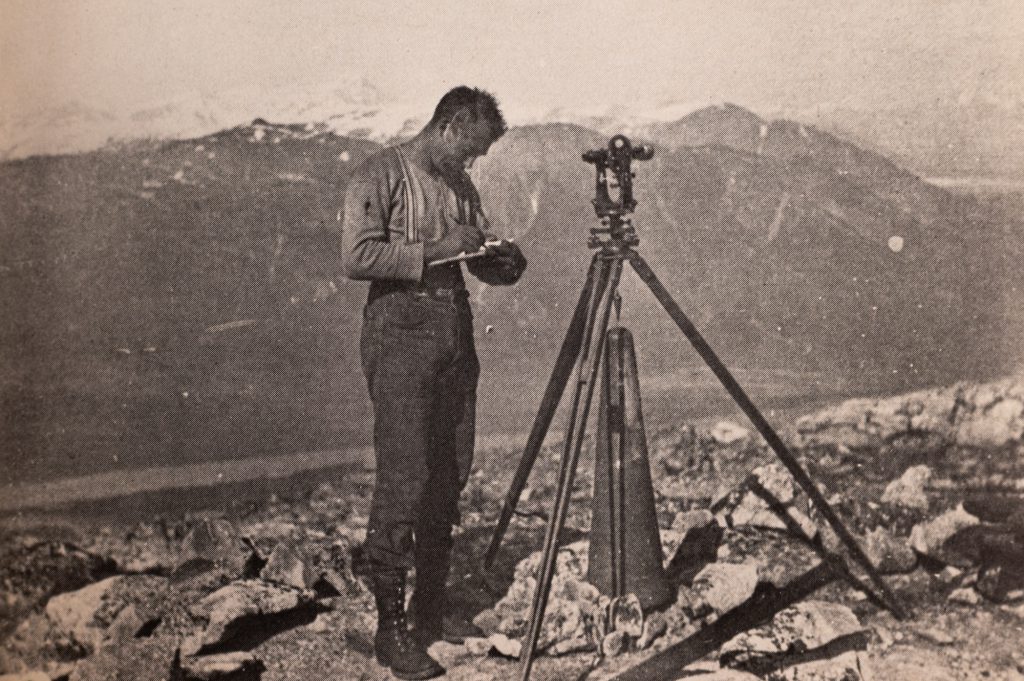

Starting in 1904, Gillespie spent three summers summiting the mountains of southeast “Alaska,” and conducting photo-topographical surveys.

Those efforts would solidify the colonial project’s border for more than a century to come.

Efforts to determine, survey, and enforce state borders has had a long-lasting effect on Indigenous ways of life.

Early pioneers and settlers — including my great-great-uncle — disregarded sophisticated land-management systems already used by Indigenous people for thousands of years.

Instead, settlers saw the land as an unknown and unused wilderness.

“The land surveyor was the pioneer of settlement,” Gillespie wrote later in his life, “and blazed the trails into the unknown parts of the province.

“Today some of those trails are paved roads and (one) travels in a few hours by airplane or motor car to those unsettled districts, where before it took weeks or months by pack-horse, canoe, backpacking, and even dog team to reach.”

A lasting scar of two colonial states

But for the Tlingit people who welcome me on their canoe journey — and generations of their ancestors — Tlingit homelands are not “unknown” parts, nor “unsettled districts.”

And their land is not a disposable asset to be merely converted into material wealth as efficiently as possible.

The pervasive concept of land as “unknown” and “empty” was common in colonial projects globally, explains Walia.

“It is really this idea that if land is not being used for capitalist purposes — which is to say if land is not marked, boundaried, surveyed, and mapped in particular ways — then that land was so-called ‘unproductive,’” she says.

This attitude, rooted in a Western capitalist worldview, helped legitimize the seizure and exploitation of Indigenous lands by settlers, under the guise of “progress” and “modernization,” Walia adds.

I ponder Gillespie’s excitement and sense of adventure, which seem to overshadow the gravity of his survey team’s mission.

As we canoe past the mountains that cradle the T’aaḵú Héeni watershed, I imagine my great-great-uncle’s survey crew hiking up the steep, snow-covered peaks around us — blazing their trails, and leaving a lasting scar of two colonial states across Tlingit territories.

“It was my first experience of mountain climbing and I was thrilled,” Gillespie writes in his memoir. “The mountain peaks chosen as boundary peaks were climbed and angles read and photos taken.

“Bronze monuments, conical in shape, about three feet high, marked with Canada on one side and United States on the other, were set at various distances along the line.”

‘Difficulties of a colonial border’

Today, that line dividing “B.C.” from “Alaska” now stretches over 2,300 kilometres, crossing the lands, communities, and villages of nations including the Tlingit, Tsimshian, Haida, Ahtna, Tutchone, Upper Tanana, Han, Gwich’in, and Inupiaq.

The border has affected Indigenous family and social ties, plus land and water stewardship systems, governance, traditional practices, language, economic opportunities, and more.

“The impacts of colonial borders have created barriers for all Tlingit communities,” says Daas.oox̱ Kirby, a child of the T’aaḵú Ḵwáan and member of Taku River Tlingit First Nation, who works with a team revitalizing the Tlingit language.

“Only two generations back, our people would be born on and travel along T’aaḵú Héeni,” she adds. “But now the colonial governments attempt to make us justify our travels for harvesting, for ceremony, and our way of life in general.”

Daas.oox̱ is of the L’uknax.ádi (coho salmon) clan from Sheet’ká (“Sitka, Alaska”).

But because her father was of the Yanÿeidí (wolf) clan, she was raised in Áa Tlein (“Atlin, B.C.”) on the other side of the border from her matrilineal clan lineage.

“Because of the border, I’m separated from my clan systems and governing ways,” Daas.oox̱ says. “I can’t easily participate in hosting a ku.éex’ (potlatch) and other cultural events.

“And I’m sure that’s quite common — where people end up really far from where their clan originates, with the added difficulties of a colonial border.”

‘Where relationships are built’

Mark Connor, fisheries co-ordinator for the Taku River Tlingit, describes how the border has “balkanized” the Tlingit people — dividing their homelands up, and disrupting their ancient stewardship practices including managing salmon in their waters.

Colonial policies further block opportunities for building connections across borders, he adds.

The Pacific Salmon Treaty, for instance, was created for “Canada” and the “U.S.” to co-operate in managing Pacific salmon stocks.

But decision-making remains rooted in colonial frameworks, Connor says, leaving some Tlingit voices unheard.

“There’s no Alaskan Tlingit representation at those tables,” he says. “Those discussion tables are places where relationships are built — and the fact that there aren’t some Tlingit people at that table makes co-management that much harder.”

The border’s impacts on culture happen in other subtle ways, too.

Earlier this year, I interviewed Tlingit weaver Donedin Jackson about her work. She said the border prevents her from fully engaging in the revitalization of Chilkat and Ravenstail weavings.

For example, she recounted applying to become an artist-in-residence at the Sheldon Jackson Museum in Dzántik’i Héeni (“Juneau”).

The museum initially expressed excitement to host her, she said, but later regretfully declined her application because she’s from the “Canadian” side of the border.

“That silly line got in the way,” she said. “Because I am on the wrong side of the border.

“Even though these are my people. This is my practice. But I don’t qualify because of that stupid line in the sand.”

The Tlingit story has parallels across Turtle Island — and across the world.

I grew up on the homelands of the Sinixt, a people displaced across the border into the U.S. beginning in the late 1800s. The border and reserve system made travel more difficult, and the Nation was later declared “extinct” by the Government of Canada in 1956.

Similar to the Tlingit, an annual Sinixt canoe journey starts in “Canada” and culminates in a ceremony in the “U.S.”

For the Sinixt people, the event is a way to assert and celebrate their existence and sovereignty.

A journey’s end — and another beginning

Since re-tracing the footsteps of my own not-so-distant ancestor, Gillespie, I keep reflecting on the legacy he and his colonial peers left behind — a legacy Tlingit and other nations have inherited.

It’s one that I, too, have inherited.

I can’t separate myself from this history, as much as I might wish to. Gillespie’s actions are part of my family’s legacy, and by extension part of my own identity.

The identity of “Canada” itself is inseparable from its borders — including the one my great-great-uncle surveyed — whether they are boundaries between colonial states, or other types of colonial lines that for centuries have displaced and dispossessed Indigenous peoples from their lands.

I think of the borders around reserves that have constricted Indigenous lands and peoples, and the walls that kept Indigenous children confined within residential “schools.”

Paulette Regan writes in Unsettling the Settler Within about what she calls settler amnesia — forgetfulness that surrounds Canada’s colonial past — including residential “schools.”

“How will Canadians who have so selectively forgotten this ‘sad chapter in our history’ now undertake to remember it?” asks the former research director for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. “Will such remembering be truly transformative or simply perpetuate colonial relations?”

As I take one step out of my amnesia — and start to see my own ancestors’ role and history in a new light — I realize my journey is only just beginning.

How will I hold and walk forward with my remembering?

The day the Taku River Tlingit First Nation canoe journey finally reaches Dzántik’i Héeni (“Juneau”) for cultural celebrations, the Tlingit pullers are joined by similar canoe journeys of the Tsimshian and Haida nations.

Hundreds of people gather on the shore, welcoming all who have journeyed to this place.

At that moment, I remember Ben Coronell’s words as we set out paddling together: “We have always been one family.”

Reporting for this story was made possible in part through a grant from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

Looking back at 2025: A year of powerful Indigenous storytelling

The Academy Awards. Reporting at the UN. Healing horses. Three generations of salmon-protectors. Multiple awards. IndigiNews reflects on our biggest stories of the year

-

After Indigenous teen’s stabbing, his family says the system failed to stop his bullying

Foster parents in ‘Courtenay, B.C.’ speak out after a string of alleged incidents targeting them and their 16-year-old foster son, as they wait for trial