Orange Shirt Day is not about buying orange shirts

Corporations are trying to turn reconciliation into a transaction — we need to disentangle its meaning from the act of shopping

Today is Orange Shirt Day, a day for acknowledging the legacy of the residential “school” system. A day for settlers to reflect and learn; a day for Indigenous people to be gentle with ourselves. As of 2021, it’s also a paid holiday for federal employees.

Orange Shirt Day was named in honour of a story shared by Phyllis Webstad (neé Jack), of the Secwepemc Nation from the Dog Creek Reserve. During a 2013 event that brought together survivors of the St. Joseph’s Mission, Webstad shared a memory of how her clothing, including her new orange shirt, was stripped from her when she arrived at the Mission in 1973.

“The colour orange has always reminded me of that and how my feelings didn’t matter, how no one cared and how I felt like I was worth nothing,” she said at the event. Her story sparked the creation of Orange Shirt Day, and its poignant tagline: Every Child Matters.

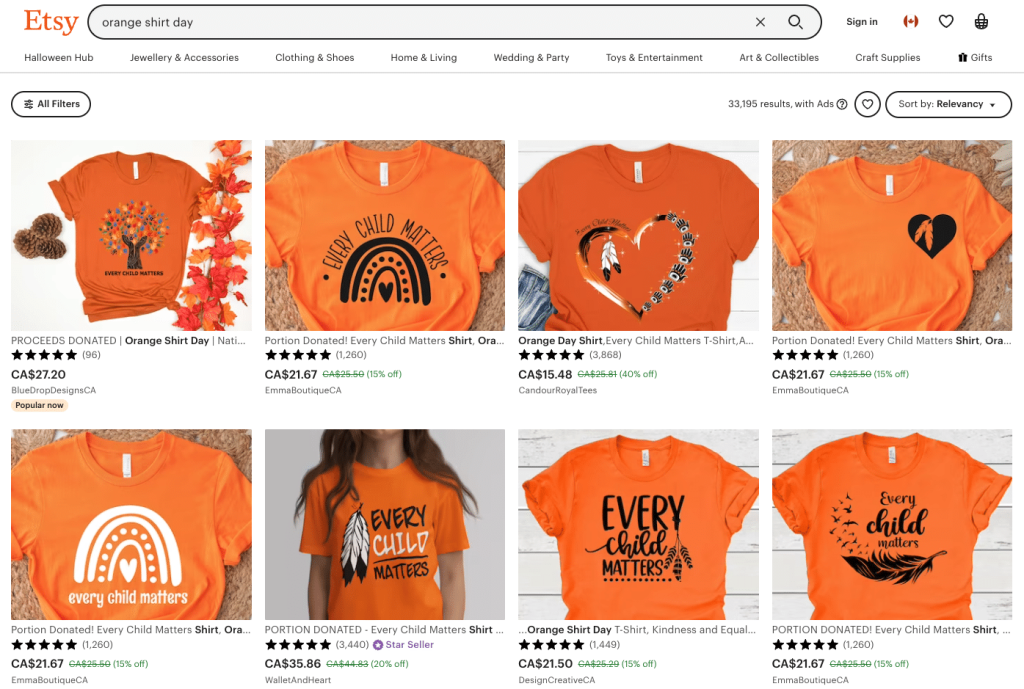

And yet, if you didn’t know Webstad’s story, you could be forgiven for thinking that Orange Shirt Day is a day for buying and selling orange shirts, and little else. In the last couple of years especially, as the horrors of residential schools have become mainstream discourse, the act of wearing an orange shirt is now customary. What began as a well-intentioned act of solidarity has been tainted by capitalism.

Everywhere you go, retailers remind you that you can pick an orange shirt up — don’t forget to buy your shirt by September 30! You can buy it at London Drugs or Walmart while grabbing toothpaste. Or you can get it shipped overnight from Etsy or Amazon, where the Indigenous designs are often stolen from artists. Each September, listicles proliferate with links to retailers. Reconciliation is available for $20, plus tax. ($40, if you got a chic cantaloupe-hued version from Aritzia before it sold out). On Twitter, a bot account has been replying to threads about Orange Shirt Day with a link to Amazon — scammers know there is money to be made off the potent combination of settler guilt and impulse shopping.

It’s distressing to see Webstad’s enduring pain, her hope for understanding, reduced to a fleeting transaction. I can’t help but wonder if the public has seized on her powerful story because they glimpsed in it a simple absolution: buy a shirt to show you care about the legacy of residential schools.

This performative awareness does represent a kind of progress. I don’t remember any of my teachers acknowledging residential schools. But when I was six — the age Webstad was when she was taken to the Mission institution — it was 1993, and many residential schools were still operating in Canada, including the one my grandmother attended. It has always been easier to condemn the past; Canadians can feel sad about residential schools without feeling implicated by them.

But I don’t see the same degree of awareness or concern among my orange-shirted neighbours for the contemporary cruelties visited on Indigenous people: racism in policing, the staggering number of children abducted by the foster care system, the ongoing practice of birth alerts, the disproportionate ravages of COVID-19. None of those horrors translate neatly to a t-shirt campaign, it’s true. But it’s hard to feel like reconciliation is moving forward when Canadians keep their gaze fixed stubbornly on the past.

And for retailers, the decision to participate is even simpler and more self-serving. Corporate partners of Orange Shirt Society, like Canadian Tire, London Drugs, Walmart and Winners, donate 100 per cent of profits. In 2021, Walmart Canada donated $147,000 to the Orange Shirt Society, after recouping all their expenses: production, shipping, marketing. Design is a minor expense: the Orange Shirt Society runs a contest each year to select the annual design — contest rules indicate that the winner receives $200. (And while I’m happy to see young Indigenous artists getting “exposure,” I believe one should receive more compensation for a design that is worn by thousands of people).

“I am not normally a fan of Walmart…” one person tweeted at me in a conversation about Orange Shirt Day, underscoring the real reason this date has been embraced so eagerly by retailers. It is an excellent PR opportunity and it costs them nothing: all of the money they donate comes from t-shirt purchases. Walmart isn’t reaching into its own pockets to support Indigenous organizations, though it could afford to: in 2021, the corporation reported nearly $139-billion in profit. And some businesses are even more opportunistic, using Indigenous designs without permission, making vague donation promises while keeping profits for themselves. Call it orange-washing: a gesture towards reconciliation that benefits the business most of all.

I believe Orange Shirt Day has profound value. I’ve heard from many Elders who are moved by the sight of those orange shirts, seeing their trauma finally acknowledged after decades of denial. And many people make a point to purchase their shirt from Indigenous artists or organizations, which is certainly the best option if you buy one — ideally, while also supporting Indigenous businesses on the other 364 days of the year. But it’s necessary, even urgent, to disentangle the meaning of the day from the act of shopping. After all, at some point we’ll all have enough orange shirts in our closet. What then?

I shudder to think of people treating orange shirts as disposable, but some of them surely are: in Vancouver, each resident throws away the equivalent of 44 t-shirts every year. The textile industry is the third-largest global source of pollution and a major driver of climate change — a crisis that disproportionately affects Indigenous people.

It’s also an industry rife with human rights abuses. At London Drugs, I noticed that the orange shirts were manufactured by Gildan in Honduras, then imported to Europe. Leaving aside the carbon emissions required to make that journey, Gildan’s eight Honduran factories have engaged in all manner of well-documented human rights abuses over the years, including exposing employees to hazardous particulate and firing workers who received injuries on the job. The cost of fast fashion is always paid by someone, and one lesson I hope everyone takes from the legacy of residential schools is not to turn away from others’ suffering in order to spare ourselves discomfort.

If you already have an orange shirt, why not just donate the money you would have spent on a new one to the Orange Shirt Society or another Indigenous organization? Then they receive the full amount, rather than a fraction, and you can leave the corporation out of it. Wear the shirt you have, year after year, and not just on September 30. Find other ways to mark the date that ask you to do more than swipe your debit card. Reconciliation is more than a transaction.

Author

Latest Stories

-

‘Bring her home’: How Buffalo Woman was identified as Ashlee Shingoose

The Anishininew mother as been missing since 2022 — now, her family is one step closer to bringing her home as the Province of Manitoba vows to search for her

-

Frustration grows over premier’s plan to alter Indigenous rights legislation

‘B.C.’s’ DRIPA law was touted as a reconciliation milestone. Now a series of court rulings has David Eby wanting to change it — a plan one lawyer calls ‘extremely offensive’

-

Looking back at 2025: A year of powerful Indigenous storytelling

The Academy Awards. Reporting at the UN. Healing horses. Three generations of salmon-protectors. Multiple awards. IndigiNews reflects on our biggest stories of the year