Truth is a journey that we walk one story at a time

On the National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, also known as Orange Shirt Day, I’m thinking about all the voices that have been silenced — and the ways we can start to heal

Editor’s note: This story was originally published in French with La Converse in September 2021 and is republished with edits and permission.

The following contains details about time in residential ‘school.’ Please read with care.

My mother didn’t say “I love you,” but she showed it in every move she made. Her strong smooth brown hands were something I admired. I remember clearly being six or seven, watching her beautiful hands. As I grew older, these hands took on more meaning. Calm hands that never struck, and moved with deliberation and care.

Mom never told us she went to residential “school.” She would say small things in passing, about “the nuns.” It felt different, but no one explained how. My mom had married at 18 and moved to “B.C.” — far away from her early life.

It would come out when she was braiding our hair. Sitting in front of her on the floor, I’d close my eyes and enjoy the slow, steady brushing. Thinking out loud, she’d let out fragments, I’d only catch something about “the nuns.”

When I left home for college, she started saying “I love you,” on the phone. When I came home from my first year, she braided my hair while we watched TV. There was a CBC miniseries about the residential “schools.”

“This didn’t happen to you, right?” I asked.

Mom’s mouth worked. She didn’t look at me; she was thinking. Finally, in a neutral voice she said, “Yes.”

In the years that followed, pieces came together, a little at a time.

It explained the silence.

Not just about residential schools, but our home. It was a quiet one. My mom wouldn’t engage in any intensity or passionate debate of any kind. She would go downstairs and do laundry and cry during an argument, rather than speak her mind.

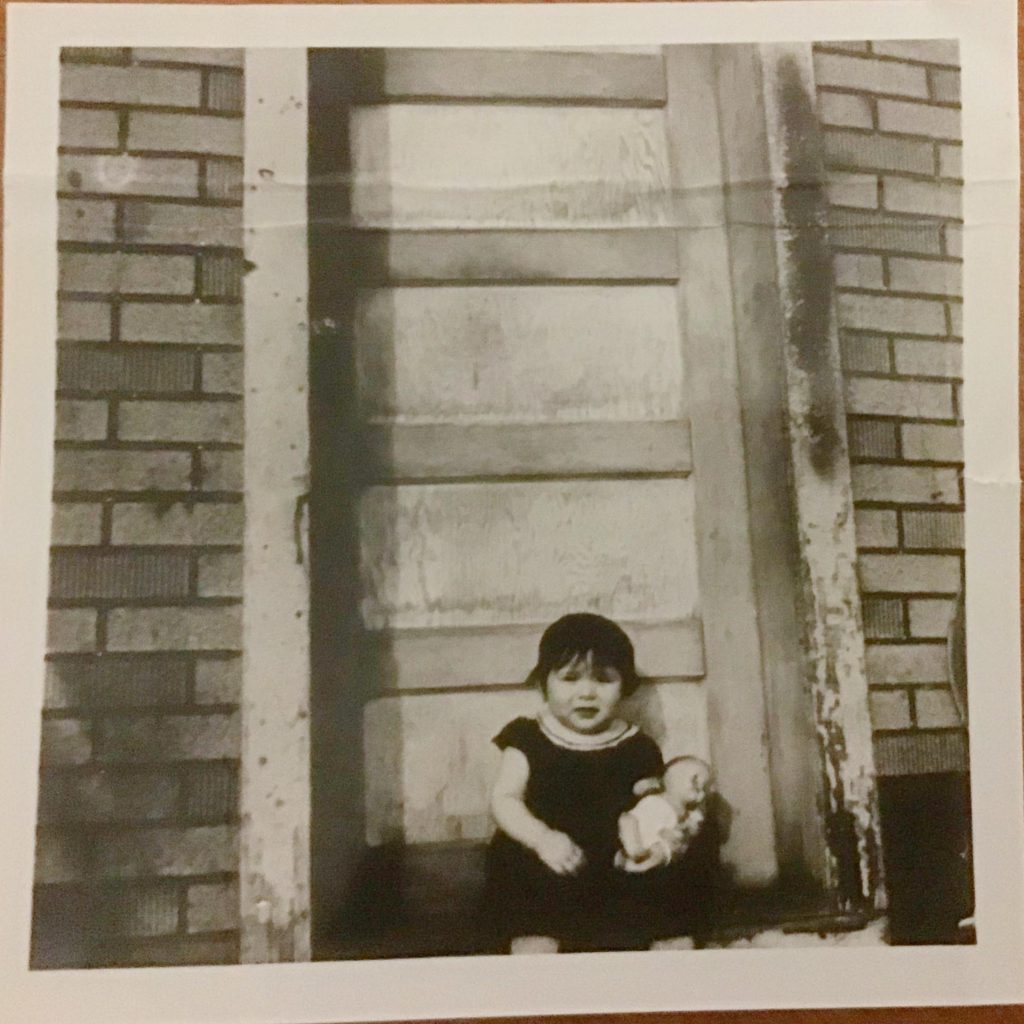

My mom was taken to residential “school” when she was seven.

“The nuns” she spoke of were the Daughters of the Heart of Mary, and they ran a girls’ residential “school” in “Spanish, Ontario.” It was operated in partnership with the Government of Canada. The boy’s school was the largest residential school in “Ontario.” They operated as one school known as the Spanish Indian Residential School by the Jesuit order.

My mom only went home for holidays, even though home was just across the river. She only spoke Anishinaabemowin and didn’t understand anything that was said to her.

“I didn’t know anything, not even that I had to raise my hand to go to the bathroom. So I wet my seat and got beaten for it.”

She answers my questions now, the night before the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. She’s held it in for over sixty years, but she answers in a straight forward, steady way. Her way.

Articles, films, stories had told me more about residential “schools” than my own mom. That’s what informed me: fellow storytellers. So I think of their stories, and ask if there were older kids who were there longer and could translate? Yes, two of her cousins were in her same class. “But, they could only help me if they were told to,” she says.

“I didn’t understand and that never went away,” she continues. “It was just — confusing. I never understood what was happening and the fear and confusion didn’t ever go away.”

My youngest child is eight years old. He’s in the next room, so I find myself matching my mom’s deliberate, calm voice. I find myself double checking, hoping it was a day school even though I know it wasn’t. My mind’s eye doesn’t want to think of her small self, there at night.

“I stayed there until Christmas, or summer. Even though my home was right across the river.”

It’s the thought of my mom being alone that pains me most.

Gabor Maté says that’s why trauma forms — not just the hurt itself. “[Children] get traumatized because they’re alone with the hurt,” he says.

That feels right in so many ways, it’s unbearable. My mom is someone who always liked us kids being around, close. She’s raised four kids and a grandchild. She’s seen many reasons why a protective eye is needed.

My mom describes being left. In her word choice more than her tone, I understand. She didn’t have that shifting moment we’ve learned about in books. Where the child has grown up, and realizes it pained parents to leave their kids.

“My parents believed in the church — the education system — and they brought me there.”

I’ve learned about survivors’ lives changing when they hear that wasn’t a choice, it was forced. Maybe my mom hasn’t had that moment.

I take a breath, and say, “Mom. They were threatened with jail if they didn’t cooperate, right?”

Her voice changes, a bit of ease in it now, lighter.

She knew that, right? I ask myself. There’s no way she didn’t know it was enforced. She had to have known, but what if she didn’t feel it? The residential “schools” were another way the government tried to break down Indigenous families and the churches were involved.

I wanted a photo from my mom for this story, the one I had in mind was a class photo at the Spanish River “school.”

“It’s gone. I tore it up. One day I was so angry at the Catholic Church, I just tore it up,” she told me that night. I raised my eyebrows over the phone, because it’s unlike her. She repeated the sentence (also unlike her) to emphasize. I smile a little, visualizing.

This is how we’re healing.

As a journalist, I speak with a lot of people. I hear teachings in every interview, whether it’s a story of heartbreaking racism or about a brilliant project. Story sharing has brought the gifts of insight. Sometimes, it brings me new entry points to talk to my mom.

I wrote about language initiatives while I was taking my first Ojibway class. My mom seemed a bit standoffish, telling me, “It’s too hard to learn.” For decades I would bristle and clam up at any dismissiveness. Now I pause and try again. I tell mom I’m taking the class with my sixteen year old, it’s our time together and it’s fun. I passed along a teaching I received through a bright young syilx language teacher. Her Elder explained what lies behind hesitant older learners and silent speakers. They can’t speak it out loud until their pain is healed.

My mom relaxes into this teaching and her voice changes. I hear her nodding, mmhmm. This is when she first tells me, “I only spoke the language until I was seven. And, getting hit any time I spoke it, makes it hard. It’s there, but I just can’t get my mouth around it.”

Why didn’t she tell us?

We would have understood her, we would have felt less frustrated when she detached from emotional things. Instead, I share what an Elder explained at a blanket exercise in Klahoose homelands. In that circle, I asked the question and he answered. We didn’t talk about it, because we didn’t want our grandkids to feel that pain. Mom agrees with a sound: mmm.

The silencing was one of the continuing impacts. I say “was” because we are talking about it now. With each fresh share from my mom, my world shifts, recalibrates. We’re closer.

Mom makes a point to tell me, “Now, to be clear: there were others who had it much worse than I did in those places.” She wants me to know so I don’t wonder. But, she’s also doing herself a disservice, diminishing her early childhood pain. It doesn’t feel right to ask more right now, so I’ll come back to that with her next time.

Despite that introduction to so-called “education” my mom valued higher learning. When she was in her late 30s she started working in healthcare, upgrading and laddering diplomas as she went. She graduated as a nurse the same month she turned 50. In a full circle way, she returned to her home territory to work with Elders in long term care.

My mom says this new National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, also known as Orange Shirt Day, doesn’t change anything that happened. I understand why she feels that way. There are so many action items, and neither of us have faith in any government.

But my mom is talking to me about what has hurt us. We’re connecting, and that’s growing.

I love you, mom.

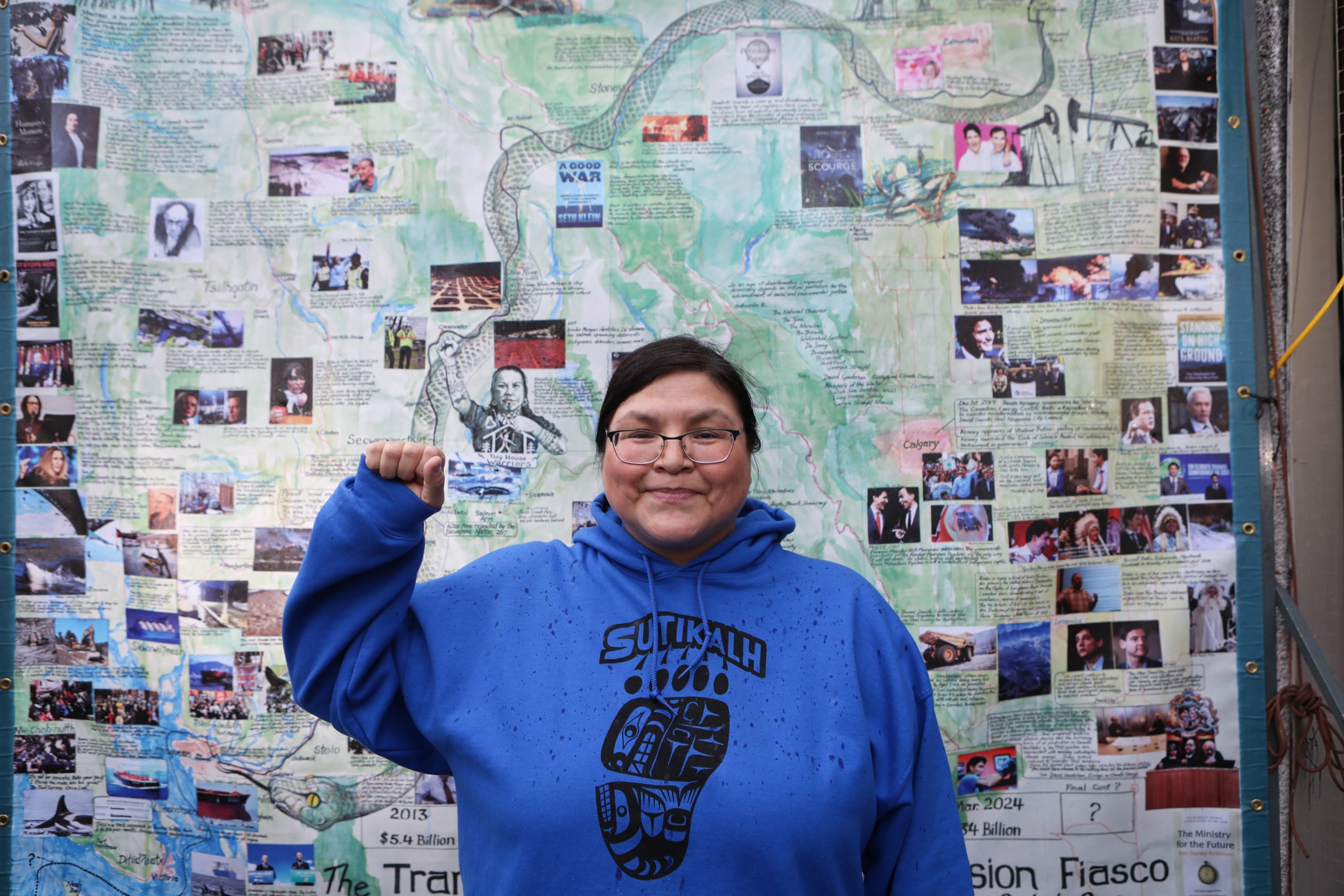

Author

Latest Stories

-

Exhibition explores ‘total visual languages’ binding Salish peoples together

New feature, ‘Every River Has a Mouth,’ highlights interconnectivity between Coast and Interior Salish artists at the Bill Reid Gallery

-

Inquest continues into ‘Winnipeg’ police shooting death of Eishia Hudson, 16

Non-adversarial probe of teen’s death cannot assign blame, but family and First Nations hope it will recommend meaningful ways to prevent similar police shootings