‘The border crossed us’: Art exhibition explores the human costs of the 49th parallel

New gallery show confronts how the ‘Canada-U.S.’ boundary broke apart Indigenous territories

This story was originally printed in Windspeaker and appears here with minor style edits.

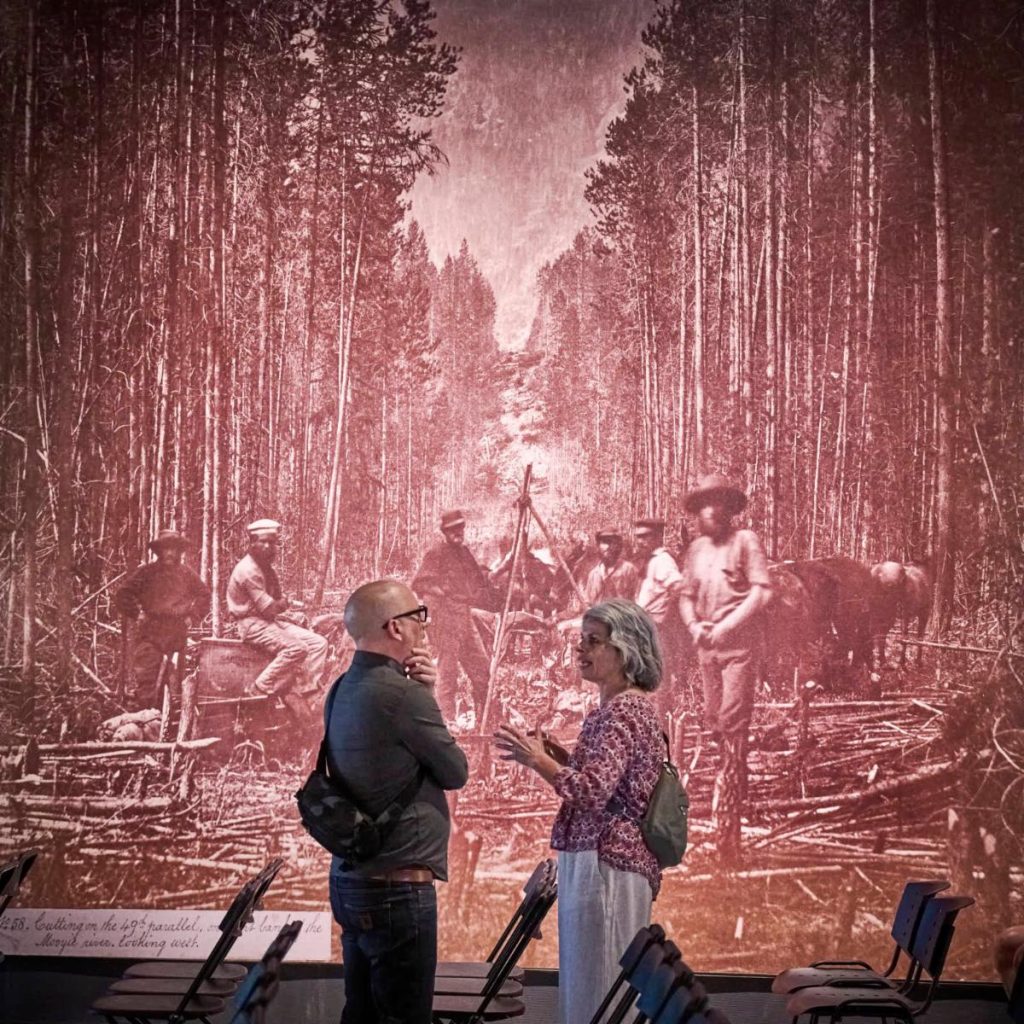

A new exhibition is confronting one of the enduring legacies of colonial mapping in “Canada”: The drawing of the 49th parallel and its impact on First Nations communities whose territories, cultures, and ceremonial travel long pre-date any border with the “United States.”

Running until May 30, 2026 at The Reach Gallery Museum in “Abbotsford,” Parallax(e): Perspectives on the Canada–U.S. Border presents historical materials with new works by Indigenous artists that reveals what official maps omitted.

“The border created divisions and conflicts between our communities and within our family,” said Sḵwx̱wú7mesh storyteller and artist T’uy’t’tanat Cease Wyss, one of the exhibit’s Indigenous curatorial collaborators.

“We have never had the right to address or protest the border,” Wyss added. “As the Indigenous hip-hop group Aztlan Underground states: ‘We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us.’

“Our voices and expressions are helping to bring visibility to the communities where these borders exist.”

The seeds of Parallax(e)

The gallery’s curator of art and visual culture, Kelley Tialiou, explained how the exhibit grew.

“The initial conceptual seeds of the exhibition were first planted seven years ago as a set of conversations between The Reach’s former executive director, Laura Schneider, and a group of transboundary scholars and artists,” she said.

Schneider sought out art historian Julia Lum, whose research into the visual record of the 1858 to 1862 Northwest Boundary Survey revealed that some of the earliest colonial images of the Pacific Northwest were produced during that expedition, Tialiou said.

Lum found that the British team created some of the first regional photographs using the wet-collodion technique, while the American surveyors enlisted James Madison Alden to produce watercolours.

These images, Tialiou emphasized, only constituted a partial view of a larger lived geography.

“The settler-colonial border along the 49th parallel cut through Indigenous territories with their own sovereign boundaries,” she noted.

Understanding this, The Reach brought Indigenous artists and curators directly into the exhibition process, including Wyss, Michelle Jack, Deb Silver, Shawn Brigman, and Carrielynn Victor.

The same colonial worldview that drew the border and produced these images also influenced the forced movement of labourers to the coast, including Wyss’s Hawai‘ian ancestors.

Kanaka Ranch: Shaped by colonial border logic

Wyss’s contribution to the exhibit is rooted in her family’s connection to Kanaka Ranch, a settlement located in what is now known as “Maple Ridge.”

It was created by the Hudson’s Bay Company when Hawai’ian labourers were brought to the coast in the nineteenth century as part of colonial labour strategies that disregarded Indigenous territorial sovereignty.

“The story of Kanaka Ranch addresses the challenges faced by my Hawai’ian ancestors who were being brought to this land, in that their origins of travelling here were disguised as sustainable work and a promise to be brought home,” Wyss said.

“They were never really brought home … many didn’t return home ever,” she said.

“They arrived and were given land … and were generally treated with better regard than the Indigenous peoples in these lands.”

By including Kanaka Ranch in Parallax(e), Wyss places her family’s displacement within a broader colonial framework — one that relocated people with or without their consent, established hierarchies of belonging, and worked in concert with the drawing of the border to reshape who was allowed to move freely along the coast and who wasn’t.

Her family story demonstrates that the colonial border was not only a physical line, but part of a broader goal of controlling territory, mobility, and identity.

“It was never about asking Indigenous peoples if we cared or not. It was always about everything that colonialism is: take the lands, plant their flags, [and] impose their violent settler belief systems on us.”

Indigenous maps that tell a different story

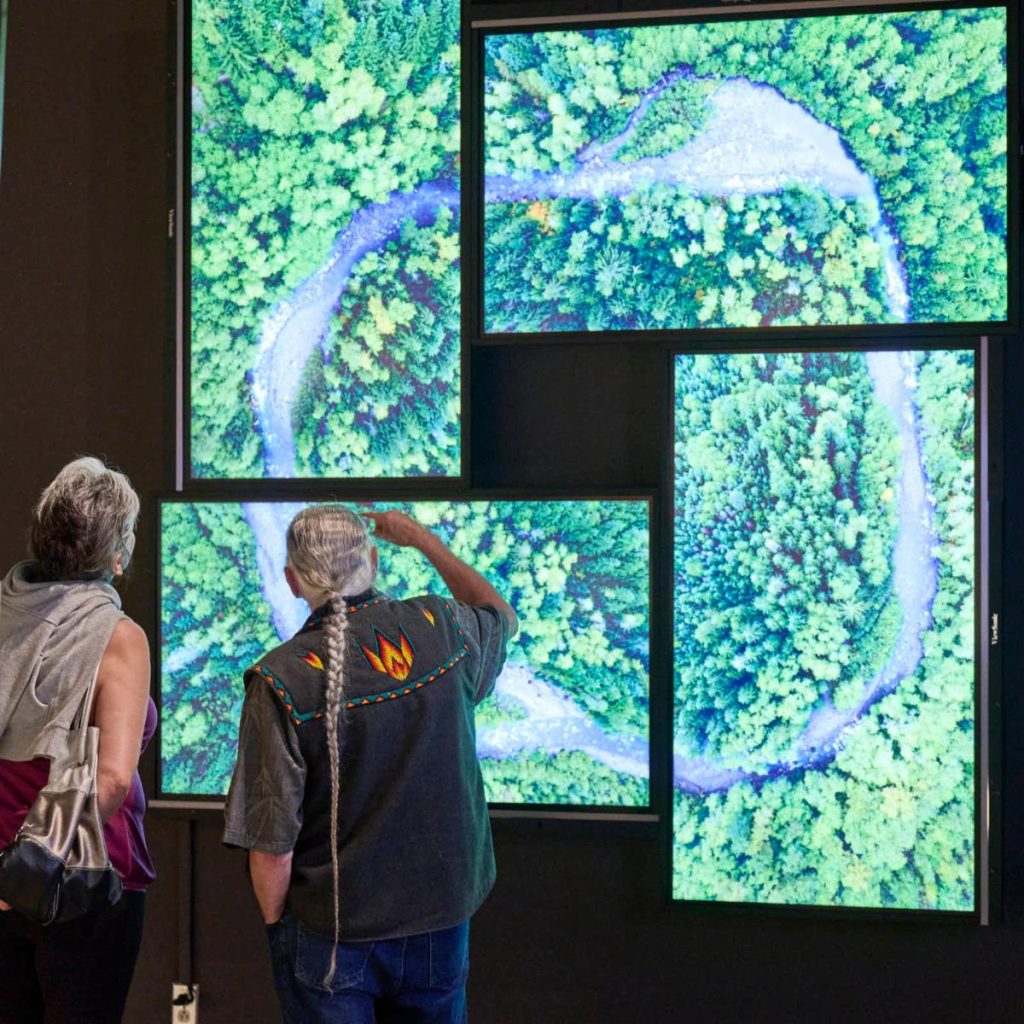

The exhibition features two 1859 maps by Indigenous mapmakers Thiusoloc and Thiusoloc’s father, reasserting Indigenous cartography over territories later cut by the 49th parallel.

“The maps … represent distance as a factor of travel time and, in doing so, reflect the intimate inherited knowledge and lived experience of the land that Indigenous people have had since time immemorial,” Tialiou said.

Rather than mapping land as commodity, these maps visualize a relationship of respect.

“They can also be understood as visualizations of the deep respect that Indigenous people had and continue to have for the land as a source of wisdom to be honoured, rather than a source of profit.”

This stands in contrast to colonial cartography, which disrupted natural and cultural landmarks in the name of state boundary-making.

For Wyss, one of the most significant elements of Parallax(e) is that Indigenous artists were empowered to share their views, rather than being merely represented from a colonial perspective.

“This collaboration was really revolutionary in that the artists themselves became part of the curatorial process of this show,” Wyss shared. “It allowed the artists more say in what and how we presented our bodies of work.”

Asked about the role of art in challenging colonial borders, Wyss replied: “If the art is created … by Indigenous people, it is addressing our concerns that we never were allowed to express throughout our lives.”

Since opening, the exhibition has prompted strong reactions.

“It’s been a journey of learning from community members,” Wyss said. “I’m still processing the feedback. Overall, it has been reaffirming to hear people’s responses and to understand what these stories … have brought up for everyone.”

Wyss hopes the exhibition leads non-Indigenous audiences to fully confront the realities of colonial border-making.

“I hope that this show helps to highlight the many layers of racism, violence, sexism, and so many issues that make folks understand how oppressive forced borders are and how much they create divisions,” she said.

“We are all in continued grief mode over the separation between our communities and neighbours since the implementation of that border.”

The exhibition concludes with works that transcend state lines, visualizing territories as homelands instead of partitions.

Through ancestral mapping, objects, language, sound, and story, Parallax(e) asks visitors not just to look at the border, but to re-see it — or not see it at all.

Author

Latest Stories

-

syilx rocker Francis Baptiste ‘hoping for a little more’ with release of newest album

Osoyoos Indian Band songwriter’s latest alt-rock release, ‘Lived Experience in East Vancouver,’ aims to ‘help people who struggled’ like artist did